Fulbright University Vietnam

┬® 2025 Korea University Institute for Sinographic Literatures and Philology

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

1) David Marr, ŌĆ£The Dong Kinh Nghia ThucŌĆØ in Vietnamese Anticolonialism, 1885-1925 (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1971), pp.156-184.

5) V┼® ─Éß╗®c Bß║▒ng, ŌĆ£Tonkin Free School Movement 1907ŌĆō1908ŌĆØ (1973), op.cit., 30-95; see also National Archives of Japan, ŌĆ£─É├┤ng Du ŌĆō A Political Movement to Gain Education from JapanŌĆØ (2013) accessible at https://shorturl.at/Pobnw. In his doctoral dissertation titled ŌĆ£The Vietnam Independent Education Movement (1900-1908)ŌĆØ (University of California, Los Angeles, 1971)81-104, V┼® also reserves a chapter called ŌĆ£The Dong Kinh Free SchoolŌĆØ to discuss the school in its socio-political, cultural and economic contexts of the time.

11) Huß╗│nh Th├║c Kh├Īng, Bß╗®c thŲ░ b├Ł mß║Łt cß╗¦a cß╗ź Huß╗│nh Th├║c Kh├Īng trß║Ż lß╗Øi cß╗ź Kß╗│ Ngoß║Īi Hß║¦u CŲ░ß╗Øng ─Éß╗ā n─ām 1943 (The secret letter from Huß╗│nh Th├║c Kh├Īng in response to Kß╗│ Ngoß║Īi Hß║¦u CŲ░ß╗Øng ─Éß╗ā in 1943), (Huß║┐: Anh Minh, 1957), p.36.

12) This is, in fact, Yan FuŌĆÖs ÕÜ┤ÕŠ® Chinese translation of John Stuart MillŌĆÖs On Liberty, first published in 1903.

14) Nguyß╗ģn Hiß║┐n L├¬, ─É├┤ng Kinh Ngh─®a Thß╗źc, 2nd edition, (Saigon: L├Ī Bß╗æi, 1968), ŌĆ£PrefaceŌĆØ for the second edition, no page numbers.

16) V┼® ─Éß╗®c Bß║▒ng, ŌĆ£─Éß║Īi hß╗Źc tŲ░ lß║Łp ─æß║¦u ti├¬n tß║Īi Viß╗ćt Nam hiß╗ćn ─æß║ĪiŌĆØ (The First Private University in Modern Vietnam), TŲ░ tŲ░ß╗¤ng, 12 (1974): 103-115; and 2 (1975): 142-163.

18) V┼® ─Éß╗®c Bß║▒ng, ŌĆ£─Éß║Īi hß╗Źc tŲ░ lß║Łp ─æß║¦u ti├¬n tß║Īi Viß╗ćt Nam hiß╗ćn ─æß║Īi,ŌĆØ TŲ░ tŲ░ß╗¤ng, 2 (1975): 147-148.

19) ChŲ░ŲĪng Th├óu, ─É├┤ng Kinh Ngh─®a Thß╗źc v├Ā Phong tr├Āo cß║Żi c├Īch v─ān ho├Ī ─æß║¦u thß║┐ kß╗Ę XX (Tonkin Free School and the Cultural Reform Movement at the Early 20th Century), (Hanoi: H├Ā Nß╗Öi Publishing House, 1982), p.24: ŌĆ£T├ón ThŲ░ is a rather broad term referring to books that contain new knowledge/learning (t├ón hß╗Źc), as opposed to the old knowledge/learning (cß╗▒u hß╗Źc) found in Confucian classics. (...) Most of these books were translations of Western works. In some cases, they were not translated directly from Western languages but through Japanese. Sometimes, only the fundamental ideas were summarized, with the primary goal being to introduce ŌĆ£Western civilization,ŌĆØ highlight its features, and promote imitation and reform. Thus, New Books became closely associated with reformist and modernization movements influenced by Western bourgeois thought in late 19th-century China. (...) These new books and newspapers had a profound impact on many patriotic intellectuals of the time. (...) It can be said that most of the Vietnamese patriots who later became key figures in movements such as the Duy T├ón [Modernization Movement], ─É├┤ng Du [Go East Movement], and Tonkin Free School were, in their early years, to some extent ŌĆśenlightenedŌĆÖ by these passionate literary and poetic works.ŌĆØ This work is reprinted in ChŲ░ŲĪng Th├óu, ─É├┤ng Kinh Ngh─®a Thß╗źc v├Ā V─ān thŲĪ ─É├┤ng Kinh Ngh─®a Thß╗źc(Hanoi: H├Ā Nß╗Öi Publishing House, 2010): vol. 1, pp.29-164.

20) Ibid., pp.8-9: ŌĆ£The issue of the Tonkin Free School received significantly more attention from researchers in socialist North Vietnam than in the South. (...) Through discussions, historians reached a consensus on several key points: the organization and leadership of the movement were led by progressive patriotic Confucian scholars, often referred to as ŌĆśConfucian scholars in the process of bourgeois transformation.ŌĆÖ The movement itself was characterized as having a bourgeois (national democratic) nature, though it was not entirely radical.ŌĆØ

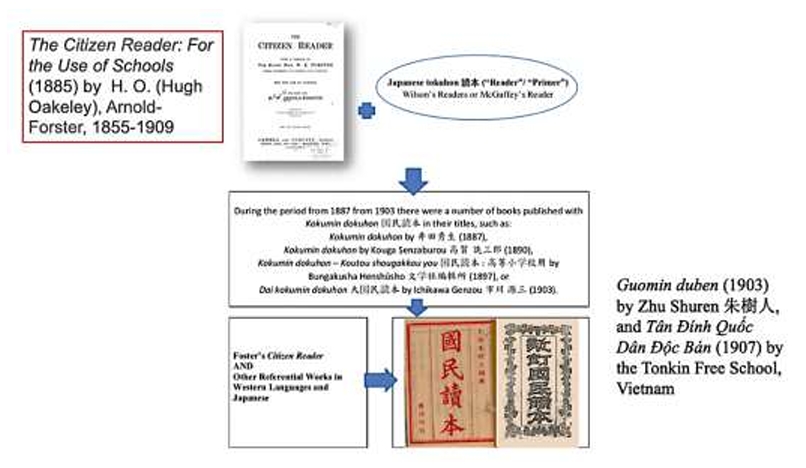

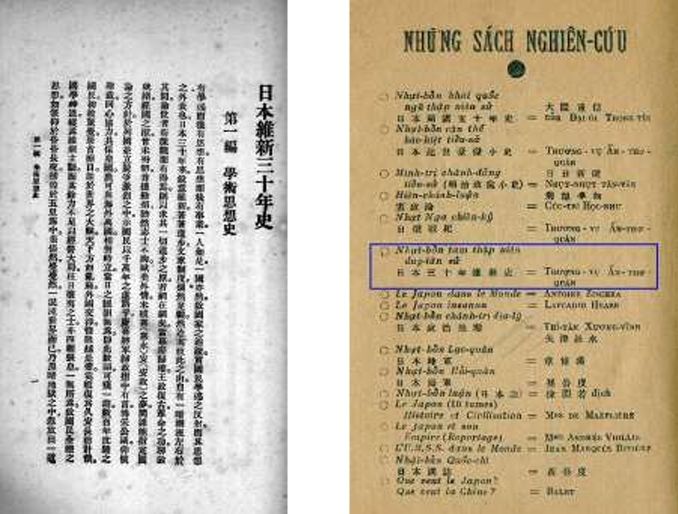

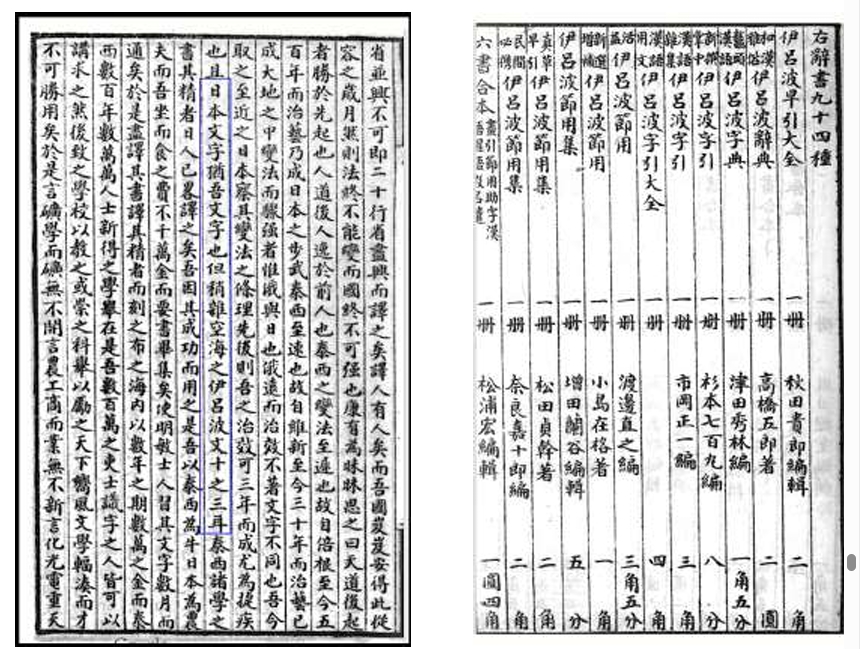

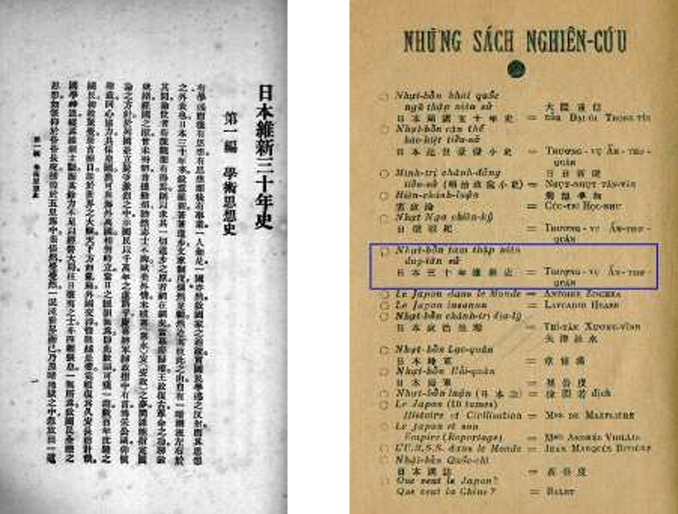

22) Nguyß╗ģn Nam, ŌĆ£Traveling Knowledge: Publications from Japan and China in Early Twentieth-Century VietnamŌĆØ in Japanese Studies Around the World õĖ¢ńĢīŃü«µŚźµ£¼ńĀöń®Č (2021): 10ŌĆō27.

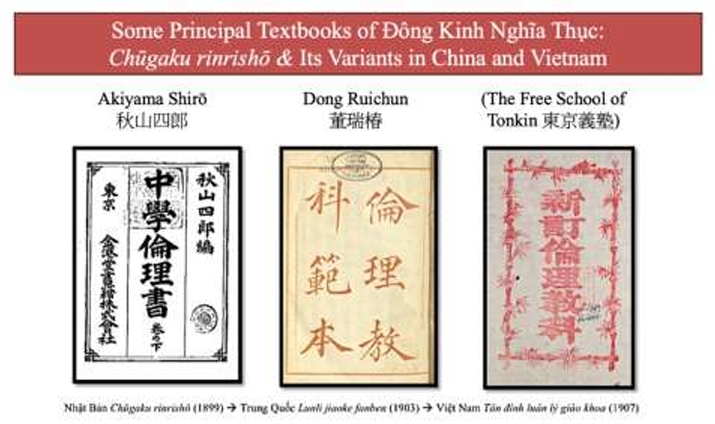

23) Nguyß╗ģn Nam, ŌĆ£Traveling Ethics Textbooks in East Asia at the End of the 19th and the Beginning of the 20th CenturiesŌĆØ ŃĆī19 õĖ¢ń┤Ƶ£½ŃüŗŃéē 20 õĖ¢ń┤ĆÕłØķĀŁŃü½ŃüŗŃüæŃü”µØ▒ŃéóŃéĖŃéóŃü«µŚģĶĪīÕĆ½ńÉåµĢÖń¦æµøĖŃĆŹ, ŃĆÄõĖŖµÖ║Õż¦ÕŁ”µĢÖĶé▓ÕŁ”Ķ½¢ķøåŃĆÅ51 (March 2017): 67-78.

24) Nguyß╗ģn Nam, ŌĆ£Thi├¬n hß║Ī vi c├┤ng: ─Éß╗Źc lß║Īi T├ón ─æ├Łnh Lu├ón l├Į Gi├Īo khoa thŲ░ tr├¬n bß╗æi cß║Żnh ─É├┤ng ├ü ─æß║¦u thß║┐ kß╗Ę 20ŌĆØ (All under Heaven Belongs to the Public: Rereading T├ón ─æ├Łnh lu├ón l├Į gi├Īo khoa thŲ░ µ¢░Ķ©éÕĆ½ńÉåµĢÖń¦æµøĖ in the East Asian Context of the Early Twentieth Century), Tß║Īp ch├Ł Nghi├¬n cß╗®u v├Ā Ph├Īt triß╗ān (Journal of Research and Development), vol. 5, 122 (2015): 121-141.

25) Traveling in place: This concept closely aligns with ngoß║Ī du ĶćźķüŖ, which can be understood as a type of imagined travel. When physical travel is not possible, one can experience distant places vicariously through paintings, travelogues, pictures, and other materials. This expression is notably employed in the VMTHS.

26) Julia Kristeva, Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art, L. S. Roudiez, ed., T. Gora, A. Jardine, & L. S. Roudiez, trans., (New York: Columbia University Press, 2024), p.64.

28) Antoine Berman, ŌĆ£Translation and the Trials of the ForeignŌĆØ in L. Venuti, ed., The Translation Studies Reader (London: Routledge, 2000), p.287.

29) Gideon Toury, Descriptive Translation Studies ŌĆō and Beyond, rev. ed., (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing, 2012), pp.76-77.

30) Lawrence Venuti, The TranslatorŌĆÖs Invisibility: A History of Translation (London: Routledge, 1995), p.17.

32) Trß║¦n Huy Liß╗ćuŌĆÖs Lß╗ŗch sß╗Ł t├Īm mŲ░ŲĪi n─ām chß╗æng Ph├Īp (History of Eighty Years of Resistance Against the French), (Hanoi: Ban Nghi├¬n cß╗®u V─ān Sß╗Ł ─Éß╗ŗa, 1956) has a chapter titled ŌĆ£Tonkin Free School th├Ānh lß║Łp v├Ā ß║ónh hŲ░ß╗¤ng cß╗¦a n├│ŌĆØ (The Establishment of Tonkin Free School and Its Impacts) that is based on the 1936 unpublished manuscript (p.142, note 3). In his manuscriptŌĆÖs preface written in Hanoi in 1957, Hoa Bß║▒ng recalls, ŌĆ£To write about Tonkin Free School, including its history, literature, and key figures, since 1936, in addition to collecting documents from books and newspapers, I also sought out and inquired directly with key individuals who had founded or participated in Tonkin Free School, such as L├¬ ─Éß║Īi, Ho├Āng T─āng B├Ł, Nguyß╗ģn Hß╗»u Cß║¦u, and ─É├Ām Xuy├¬n Nguyß╗ģn Phan L├Żng, among others. // By 1945, having gathered a relatively complete set of materials, I compiled them into a book titled Tonkin Free School, under the pen name Mai L├óm. However, before I could publish it, war broke out, and as a result, both the manuscript and its author were each swept away in different directions by the tide of events. // Twelve years have passed. Over time, I have continued to collect more materials. Now, in order to contribute to the available references on Vietnamese modern history and literature, I have revised and published this book, Tonkin Free School, hoping to receive constructive feedback from dear friends near and far.ŌĆØ

34) ŌĆ£A New Method to Study CivilizationŌĆØ in TrŲ░ŲĪng Bß╗Łu L├óm, Colonialism Experienced ŌĆō Vietnamese Writings on Colonialism, 1900-1931 (MI: University of Michigan, 2000), pp.141-156; and Jayne Werner and Luu Doan Huynh, trans., Tonkin Free School, ŌĆ£A Civilization of LearningŌĆØ in George E. Dutton, Jayne S. Werner, and John K. Whitmore, eds., Sources of Vietnamese Tradition, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), pp.369-375.

36) George E. Dutton, Jayne S. Werner, and John K. Whitmore, eds., Sources of Vietnamese Tradition, p.369.

37) Here is an example. When discussing civil service examination reforms in Vietnam, the VMTHS employs the phrase mß║Īi t├Łnh chi vi Ķ│ŻÕ¦ōõ╣ŗÕ£Ź. Based on ─Éß║Ęng Thai MaiŌĆÖs Vietnamese translation, TrŲ░ŲĪng Bß╗Łu L├óm renders it as ŌĆ£selling your name,ŌĆØ explaining that students often took examinations on behalf of othersŌĆöa phenomenon referred to as ŌĆ£selling oneŌĆÖs name.ŌĆØ Another form of this practice involved cheating on the exam (p.155, note 13). In contrast, Jayne Werner and LŲ░u Do├Żn Huß╗│nh omit the phrase in their translation. Both extant woodblock-printed and handwritten copies of VMTHS contain the character vi/wei Õ£Ź, which may be an alternative form of ķŚł, meaning ŌĆ£doors of the palace.ŌĆØ This character frequently appears in terms related to the civil service examination. Notably, GilesŌĆÖ English-Chinese Dictionary records weixing ķŚłÕ¦ō as ŌĆ£examination names, a form of lottery on the names of successful competitors.ŌĆØ This refers to a popular betting pool in China, in which people wagered on the surnames of top scorers in local and national examinations (weixing ķŚłÕ¦ō) (Koos Kuiper, 2017). The Early Dutch Sinologists (1854-1900): Training in Holland and China, Functions in the Netherlands Indies (2 vols.), (Leiden; Boston: Brill), vol. 2, p.856, note 5. This practice lasted for several decades but ended with the abolition of the civil service examination in China in 1905. Reports on such betting pools appeared in Chinese newspapers, which may have been imported and circulated in Vietnam. The VMTHS likely cited this phenomenon as a striking example to critique the outdated civil service examination system in both China and Vietnam. Given this context, mß║Īi t├Łnh chi vi should be translated as ŌĆ£the Palace doors of ŌĆśselling names.ŌĆÖŌĆØ

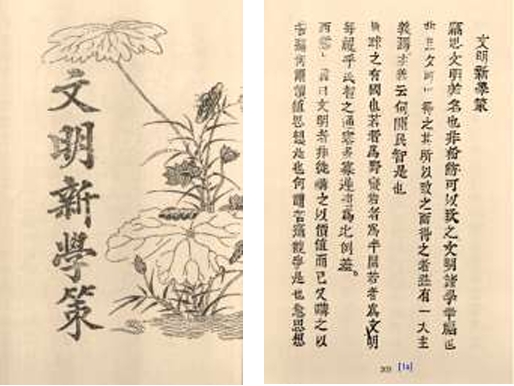

38) All citations in this section are from Anonymous, V─ān Minh T├ón Hß╗Źc S├Īch µ¢ćµśÄµ¢░ÕŁĖńŁ¢ŌĆöNew Learning Strategies for the Advancement of Civilization, 1904 (New Annotated Translation), translated and annotated by Nguyß╗ģn Nam, Nichibunken (International Research Center for Japanese Studies), 2021. It is translated directly from the woodblock-printed text reproduced in ChŲ░ŲĪng Th├óu (2010). Tonkin Free School v├Ā V─ān thŲĪ Tonkin Free School (The Tonkin Free School and Its Prose and Poetry), op. cit., vol. 1: 203-242. The Chinese origin of the citation reads, µ¢ćµśÄńŠÄÕÉŹõ╣¤ķØ×ń▓ēķŻŁÕÅ»õ╗źĶć┤õ╣ŗµ¢ćµśÄĶ½ĖÕŁĖĶŠøń”Åõ╣¤ķØ×µŚ”ÕżĢÕÅ»õ╗źÕŠŚõ╣ŗ (205). The numbers in the special brackets ŃĆÉ ŃĆærefer to the English translationŌĆÖs numbering on the same text.

39) Ķź┐ÕäÆĶ©Ćµø░µ¢ćµśÄĶĆģķØ×ÕŠÆĶ│╝õ╣ŗõ╗źÕā╣ÕĆ╝ĶĆīÕĘ▓,ÕÅłĶ│╝õ╣ŗõ╗źĶŗ”ńŚø.õĮĢĶ¼éÕā╣ÕĆ╝µĆصā│µś»õ╣¤.õĮĢĶ¼éĶŗ”ńŚøń½ČńłŁµś»õ╣¤.µäłµĆصā│Õēćµäłń½ČńłŁ,µäłń½ČńłŁÕēćµäłµĆصā│. (205-206).

40) Õ£░ńÉāõ╣ŗµ£ēÕ£ŗõ╣¤ĶŗźĶĆģńé║ķćÄĶĀ╗ĶŗźĶĆģńé║ÕŹŖķ¢ŗĶŗźĶĆģńé║µ¢ćµśÄµ»ÅĶ”¢õ╣ĵ░æµÖ║õ╣ŗķĆÜÕĪ×ÕżÜÕ»Īķü▓ķƤńé║µ»öõŠŗÕĘ«. (205).

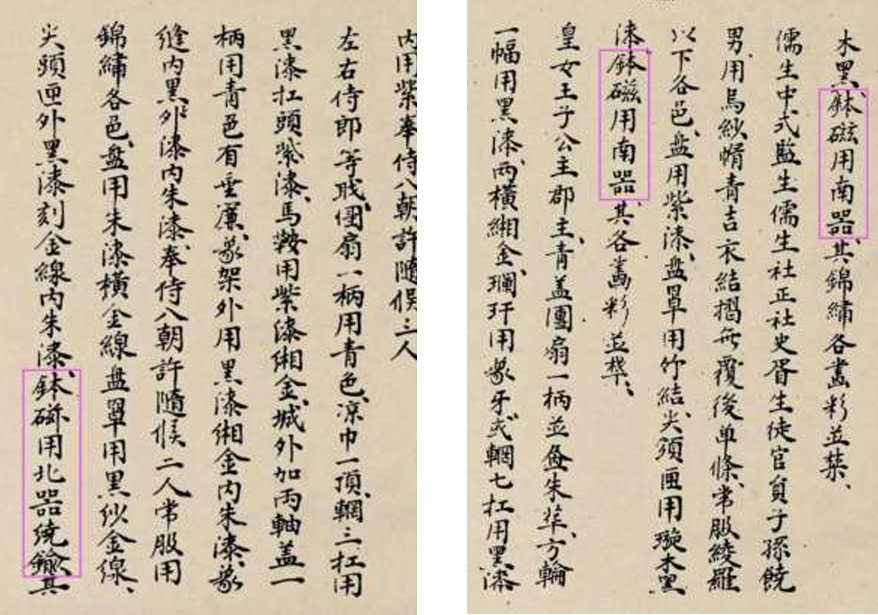

42) From silk and satin, cotton and felt, cloth and brocade, shoes and socks, handkerchiefs, eye glasses, umbrellas µŖŖķü«Õéś, petrol ńćłńü½µ▓╣, porcelain, crystals, enamel, watches ķÉśķīČ, barometers ķó©ķø©ķćØ, thermometers ջƵÜæĶĪ©, telephones ÕŠĘÕŠŗķó©, microscopes ķĪ»ÕŠ«ķÅĪ, photos ńéżńøĖńēć to stationaries, cinnabar ink, needles and threads, buttons, pigments, ŃĆÉ2bŃĆæ soap, perfume ĶŖ▒ķ£▓, matches, steamed bread, candies, medicines, cigarettes ÕĘ┤ĶÅ░ńģÖ, opium ĶŖÖĶōēńā¤, tea, wine, all kinds of commodities are purchased either from the North (China) or from the West (France): ńČóńĘ×ńĄ©ÕŻćÕĖāÕĖøķ×ŗķ¤łµēŗÕĘŠń£╝ķÅĪµŖŖķü«Õéśńćłńü½µ▓╣ńŻüÕÖ©ńÄ╗ńÆāńÉ║ÕŻÜķŹŠķīČķó©ķø©ķćØջƵÜæĶĪ©ÕŠĘÕŠŗķó©ķĪ»ÕŠ«ķÅĪńéżńøĖńēćõ╗źÕÅŖķü┐ķܬńŁåń«ŗńĪāÕó©ńĘśńĘÜķłĢķć”ķĪŵ¢ÖĶéźńÜéĶŖ▒ķ£▓ńćÉķæĮķĢśķĀŁń│Ģń│¢ĶÅōÕōüĶŚźµØÉÕĘ┤ĶÅ░ńé»ĶŖÖĶōēńé»ĶīČķģÆĶ½ĖĶ▓©ķĀģõĖŹĶ│╝õ╣ŗÕīŚÕēćĶ│ćõ╣ŗĶź┐. (207-208).

43) ÕĮ╝ńÉ┤ĶĆīń¼øĶĆīµŖĢÕŻ║ĶĆīĶæēµł▓ĶĆīÕ£ŗµŻŗĶĆīĶ®®Ķ¼ÄĶĆīÕŁŚĶ│ŁĶĆīµś¤ÕæĮĶĆīÕŹĀķ®ŚĶĆīķó©µ░┤ĶĆīń¼”ń▒ÖµŚźÕĮ╣µÖ║µ¢╝ńäĪńö©ĶĆģ. (209).

47) ÕģČķ½śńäēĶĆģÕŹÜõĖĆÕÉŹõ╣ŗÕŠĄĶÖ¤µø┤Ķ®ĪĶ®Īõ╗źķ½śõ║║Ķć¬Õ▒ģõ╗źõĖ¢ķüōĶć¬ÕæĮ(ŌĆ”)ĶĆīµ¢ćµśÄµ¢░ÕŁĖõĖĆÕłćķäÖÕżĘ. (209).

52) µŁÉµ┤▓õ╣ŗõ║║ķ揵ĖĖµŁĘĶĆīĶ╝ĢķܬĶē▒µæ®Ķź┐õ╣ŗķüĘĶ┐”ÕŹŚõ╣¤ÕøøÕŹüÕ╣┤ń¦æÕĆ½ÕĖāõ╣ŗÕŠ¼ÕŠ©µ¢╝Õż¦Ķź┐µ┤ŗõ╣¤µĢĖÕŹüÕ╣┤Õł®ńæ¬ń½ćõ╣ŗĶĘŗµČēµ¢╝µö»ķéŻõ╣¤ÕŹüõ╣ØÕ╣┤. (213).

57) Ķ┐æĶæĪĶÉäńēÖńē¦ÕĖ½ĶŻĮÕć║Õ£ŗĶ¬×ÕŁŚÕÅ¢µŁÉµ┤▓õ║īÕŹüÕģŁµ»ÅÕŁŚ(ŌĆ”)õ╗źµ£¼ķ¤│µ£Ćńł▓ń░ĪµŹĘõ╝╝Õ«£õĖĆÕŠŗĶĪīõ╣ŗ. (217).

59) See John DeFrancis, ŌĆ£First Chinese ReformersŌĆØ in The Chinese Language ŌĆō Fact and Fantasy (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1984), pp.242-243.

60) Elisabeth Kaske, The Politics of Language in Chinese Education, 1895-1919, (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2008), p.251: ŌĆ£However, a closer look shows that given the limited time allocated to the teaching of Chinese, which was obviously insufficient also to learn writing in the literary language, educators were in fact taking recourse to a double language standardŌĆöliterary reading vs. vernacular writing.ŌĆØ

61) Sun Jiahui ÕŁÖõĮ│µģ¦, ŌĆ£Letters of Revolution: The Failed Movement to Eradicate Chinese Characters,ŌĆØ The World of Chinese (2024), https://www.theworldofchinese.com/2024/05/the-failed-movement-to-eradicate-chinese-characters/

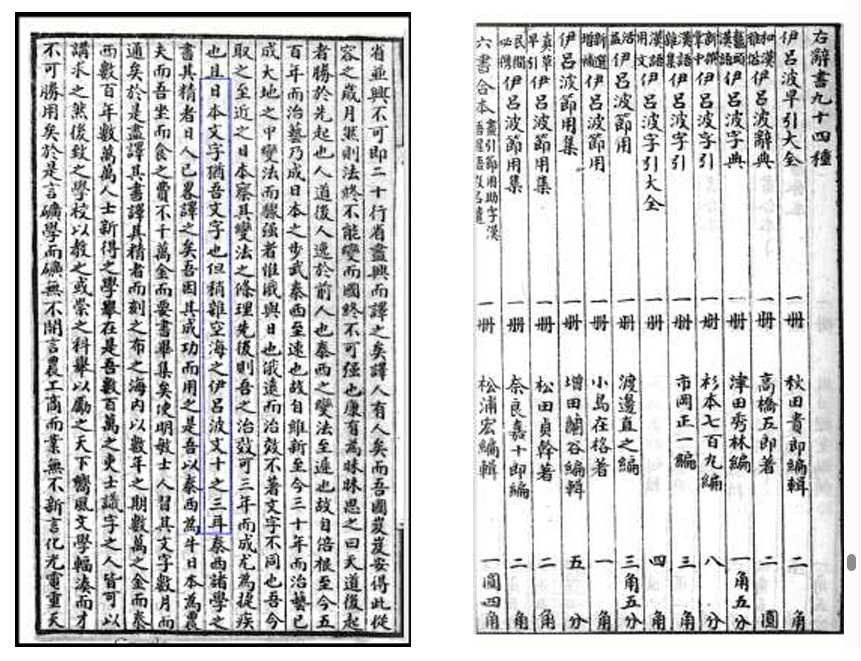

62) In his Riben shumuzhi µŚźµ£¼µøĖńø«Õ┐Ś (Catalogue of Japanese Books), (Shanghai: Datong yishuju Õż¦ķĆÜĶŁ»µøĖÕ▒Ć, ca. 1897), Kang Youwei Õ║ʵ£ēńé║ (1858-1927) describes JapanŌĆÖs writing system as follows, ŌĆ£ŌĆÖJapanese script looks like ours but slightly mixed with K┼½kaiŌĆÖs ń®║µĄĘthirteen-iroha script µŚźµ£¼µ¢ćÕŁŚńīČÕÉŠµ¢ćÕŁŚõ╣¤õĮåń©Źķø£ń®║µĄĘõ╣ŗõ╝ŖÕæéµ│óÕŹüõ╣ŗõĖēĶĆ│.ŌĆÖ K┼½kai (also known posthumously as K┼Źb┼Ź-Daishi Õ╝śµ│ĢÕż¦ÕĖ½, 774ŌĆō835) was the founder of the Esoteric Shingon ń£¤Ķ©Ć (mantra) school of Buddhism in Japan. According to Ry┼½ichi Abe, ŌĆśK┼½kai was also said to have invented kana, the Japanese phonetic orthography, and the Iroha, the kana syllabary. In the Iroha table, the kana letters are arranged in such a manner as to form a waka that plainly expresses the Buddhist principle of emptiness.ŌĆÖŌĆØ Ry┼½ichi Abe, The Weaving of Mantra ŌĆō K┼½kai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), p.3.

63) µłæÕ£ŗÕÅżõŠåõĮ£ĶĆģµ×Śń½ŗ(ŌĆ”)µłæÕ£ŗõ║║ń║öõĖĆÕģźÕŁĖõŠ┐Ķ«ĆÕīŚµøĖĶĆīńĮ«µłæÕ£ŗµøĖµ¢╝õĖŹÕĢÅ. (217 -218)

66) This may be another name for Wu dazhou tushuo õ║öÕż¦µ┤▓Õ£¢Ķ¬¬ by Ai Rulue ĶēŠÕäÆńĢź (Giulio Alenio), edited by Qian Xizuo ķīóńåÖńźÜ, published by Shanghai shuju õĖŖµĄĘµøĖÕ▒Ć in 1898.

67) This may be a shorter title of Gujin wanguo gangjian ÕÅżõ╗ŖĶɼգŗńČ▒ķææ (Singapore: Jianxia shuyuan ÕĀģÕżÅµøĖķÖó, 1838); see https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=151372&remap=gb. Although the extant publication has no authorŌĆÖs name printed, it has been attributed to Karl Friedrich G├╝tzlaff (aka. Guoshila ķāŁÕ»”Ķćś, or Guoshili ķāŁÕŻ½ń½ŗ, 1803-1851; see Guo Xiuwen ķāŁń¦Ćµ¢ć, ŌĆ£Dongxiyang kao meiyue tongjizhuan de zhongjiao chuanbo celueŃĆŖµØ▒Ķź┐µ┤ŗĶĆāµ»Åµ£łńĄ▒Ķ©śÕé│ŃĆŗńÜäÕ«ŚµĢÖÕé│µÆŁńŁ¢ńĢźŌĆØ, Xueshu yanjiu ÕŁĖĶĪōńĀöń®Č, no. 8/2016, p. 114). However, there is another book with a quite similar title, Guojin wanguo gangjianlu ÕÅżõ╗ŖĶɼգŗńČ▒ķææķīä by Robert Morrison (aka. Molisong µ©Īń”«Õ┤¦, or Malisun ķ”¼ń”«ķü£, 1782-1834), as seen in a version of it printed in Japan: Moreish├┤ µ©Īń”«Õ┤¦. Kokon bankoku k┼Źkanroku ÕÅżõ╗ŖĶɼգŗńČ▒ķæÆķīä, with Japanese guiding marks (kunten Ķ©ōńé╣) by ┼ītsuki Seishi Õż¦µ¦╗Ķ¬Āõ╣ŗ, corrected by Yanagisawa Shindai µ¤│µŠżõ┐ĪÕż¦, Tokyo: T┼Źsei Kamejir┼Ź µØ▒ńö¤õ║Ƶ¼ĪķāÄ, 1874. Confused by the resemblance of the two titles, some modern scholars consequently identify Gujin wanguo gangjian as MorrisonŌĆÖs work, as in the case of Chou Yu-wen Õ橵äܵ¢ć, ŌĆ£WanQing jiawuqian zai Hua Zhongwai renshi duiyu Meiguo jiaoyu de jieshao µÖܵĖģńö▓ÕŹłÕēŹÕ£©ĶÅ»õĖŁÕż¢õ║║ÕŻ½Õ░Źµ¢╝ńŠÄÕ£ŗµĢÖĶé▓ńÜäõ╗ŗń┤╣ (The Introduction of American Education by Missionaries and Chinese Officials and Commoners in Late ChŌĆÖing China before 1894), Jiaoyu yanjiu jikan µĢÖĶé▓ńĀöń®ČķøåÕłŖ/ Bulletin of Educational Research, vol. 65:1 (3/2019): 121.

68) It is possibly Wanguo jinzheng kaolue ĶɼգŗĶ┐æµö┐ĶĆāńĢź by Zou Tao ķäÆÕ╝ó (Shanghai: Sanjielu õĖēÕƤÕ╗¼, 1901).

69) This may be a shorter title of Xixue kaolue Ķź┐ÕŁĖĶĆāńĢź by Ding Weiliang õĖüķ¤ÖĶē» (William Alexander Parsons Martin), Tongwenguan ÕÉīµ¢ćķż©, 1883.

70) Linhan Chen and Danyan Huang, ŌĆ£Internationalization of Chinese Higher Education,ŌĆØ Higher Education Studies, vol. 3:1 (2013): 94.

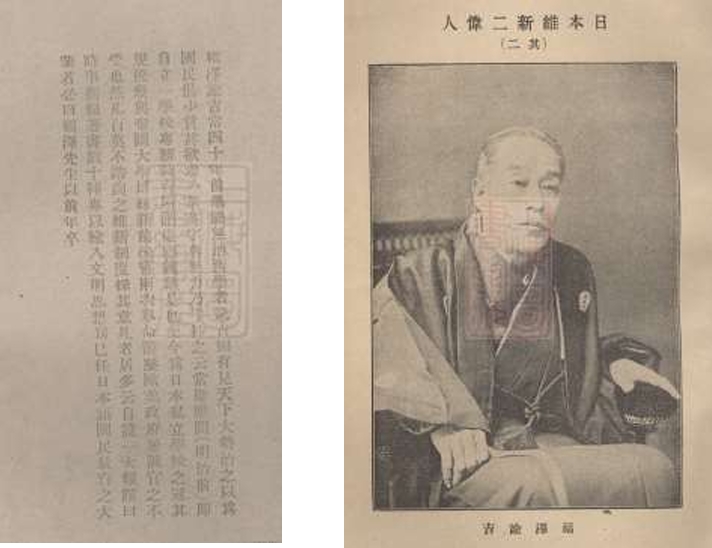

71) Masao Watanabe, trans. by Otto Theodor Benfey, The Japanese and Western Science (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1988), p.7: After Japan opened its doors in the second half of the nineteenth century, in order to catch up with the West it adopted Western knowledge as well as institutions in one fell swoop. Modern educational institutions were created that began to train their own research and teaching staffs.ŌĆØ (p.6); Japanese scientist Yamagawa Kenjir┼Ź (1854-1931) recalls, ŌĆ£In those days there were few schools in Tokyo where foreign texts could be studied. These were the Daigaku-Nank├Č [the precursor of the University of Tokyo], the Keio Gijuku of Fukuzawa Yukichi, the D├Čjinsha of Nakamura Masanao in Koishikawa, as well as the Ky├Čkan-Gijuku, which Fukuchi GenŌĆÖichiro had opened in Shitaya.ŌĆØ (p.7).

72) Ibid., pp.1-5, ŌĆ£Introduction: JapanŌĆÖs Modern CenturyŌĆØ; pp.23-40, ŌĆ£Japan Studies of Foreign Teachers in Japan: Investigations of the Magic MirrorŌĆØ.

73) Shigeru Nakayama, ŌĆ£Independence and Choice: Western Impacts on Japanese Higher Education,ŌĆØ Higher Education, vol. 18: 1 (1989), From Dependency to Autonomy: The Development of Asian Universities (1989): 31-48.

74) ńČōÕģĖńŠ®µ£Ćń▓ŠµĘ▒ĶĆīµ¼▓ÕƤµĘ║Ķ┐æõ╣ŗµ¢ćń½Āõ╗źĶ¦ĆÕ»”ÕŁĖµ£ēµś»ńÉåõ╣Ä?ńÖŠÕ«ČĶī½ńäĪń┤ƵźĄĶĆīµ¼▓ń¬«õĖĆõ║║õ╣ŗĶ©śĶ¬”õ╗źķ®Śń£¤µēŹµ£ēµś»µāģõ╣Ä? (p.223).

75) ÕÅłõĖŹń¤źÕŁĖń®ČÕģłńö¤ĶŠ░(µÖé)µ¢ćķēģÕŁÉ,ÕģČĶāĮĶŁśõ║öµ┤▓õĮĢÕÉŹĶÖ¤,õ╗ŖµŚźõĮĢõĖ¢ń┤Ćõ╣ŗõ║║ĶĆģ. (p.223).

76) In 1904, Zheng Guangong selected humorous writings and traditional Chinese telling and singing pieces of art printed in newspapers and periodicals, and published them together in a magazine called Shixie xinji µÖéĶ½¦µ¢░ķøå (New Collection of Contemporary Laughing Matters). One of its main categories is called ŌĆ£Wenjie µ¢ćńĢīŌĆØ (Literary World) divided into a number of sections, of which is the ŌĆ£Hexagram of the Civil Service Examination.ŌĆØ See Li Wanwei µØÄÕ®ēĶ¢ć, ŌĆ£Qingmo Minchu Yue Gang gemingpai baokanŌĆØ µĖģµ£½µ░æÕłØń▓ĄµĖ»ķØ®ÕæĮµ┤ŠÕĀ▒ÕłŖ, Wenshi zhishi µ¢ćÕÅ▓ń¤źĶŁś, no. 12 (2012): 31-32.

77) On August 29, 1901, an imperial edict was issued, officially abolishing the eight-legged essay in the civil examinations, ŌĆ£all examination essays whether political discourses (celun ńŁ¢Ķ½¢) or extrapolation of the Confucian Classics (jingyi ńČōńŠ®) had to be written in unbound non-metrical prose.ŌĆØ Elisabeth Kaske. The Politics of Language in Chinese Education, p.254. The abolition was a critical decision made after several memorials sent to the throne by Zhang Zhidong, Zhang Yuanji Õ╝ĄÕģāµ┐¤ and Kang Youwei (ibid., p.85), ŌĆ£signaling that examination questions for the shengyuan degree would now include Western learning (Xixue) as well as Chinese learning (Zhongxue). Moreover, it became clear that at the higher examination levels (for the juren and jinshi degrees) at least one set of policy questions would focus on ŌĆśworld politics.ŌĆÖŌĆØ Richard J. Smith, The Qing Dynasty and Traditional Chinese Culture (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015), p.393.

78) Liu Haifeng, ŌĆ£Influence of ChinaŌĆÖs Imperial Examinations on Japan, Korea and Vietnam,ŌĆØ Frontiers of History in China, vol.2:4 (1/2007): 493-512.

79) ÕÅ¢ńČōÕé│õĖēÕÅ▓õĖŁ(ÕŹŚõĖŁĶź┐)ÕæĮķĪīńÖ╝ÕĢÅĶüĮÕģČĶŁ░Ķ½¢(ŌĆ”)ńäČÕŠīÕÅāõ╣ŗõ╗źń«ŚÕŠŗÕ£ŗĶ¬×ÕŁŚµĢÖµóØõĮ┐õ╣ŗµēĆÕŁĖµēĆĶ®”ĶłćµēĆńö©õĖŹĶć│Ķāīķ”│. (p.221).

80) Both the prefaces for the Society in Beijing and Shanghai by Kang Youwei and Zhang Zhidong respectively do not contain the cited sentence. See ŌĆ£Jingshi qiangxuehui xu õ║¼ÕĖ½Õ╝ĘÕŁĖµ£āÕ║ÅŌĆØ, Qiangxuebao Õ╝ĘÕŁĖÕĀ▒, no. 1 (1895); ŌĆ£Shanghai qiangxuehui xuŌĆØ õĖŖµĄĘÕ╝ĘÕŁĖµ£āÕ║Å, Xinwen bao µ¢░Ķü×ÕĀ▒, (December 4, 1895). However, a similar sentence is found in Liang QichaoŌĆÖs letter addressed to Chen Baozhen ķÖ│Õ»Čń«┤, titled ŌĆ£Lun Hunan yingban zhi shi Ķ½¢µ╣¢ÕŹŚµćēĶŠ”õ╣ŗõ║ŗŌĆØ (On What Hunan Should Do). LiangŌĆÖs sentence reads, ŌĆ£Thus, if we now want to enlighten the peopleŌĆÖs mind, we need to enlighten the gentryŌĆÖs mind; and as we should pass it on to the mandarin force whom we still do not know all, we therefore must enlighten the mandarinŌĆÖs mind, making it the starting point of everything ÕŹ│õ╗ŖµŚźµ¼▓ķ¢ŗµ░æµÖ║’╝īķ¢ŗń┤│ µÖ║’╝īĶĆīÕüćµēŗµ¢╝Õ«śÕŖøĶĆģ’╝īÕ░ÜõĖŹń¤źÕćĪÕ╣Šõ╣¤’╝īµĢģķ¢ŗÕ«śµÖ║’╝īÕÅłńé║Ķɼõ║ŗõ╣ŗĶĄĘķ╗×ŌĆØ. The text reads, µ¼▓ķ¢ŗµ░æµÖ║’╝īÕģłķ¢ŗń┤│µÖ║. (p.221).

81) µŁżµÄĪµ£¼õ╣ŗĶć│Ķ©Ćõ╣¤Ķæóµ░æõ╣ŗÕēćÕéÜĶ”¢ń┤│ĶæŻÕŠīńö¤õ╣ŗĶ¦Ćµæ®Ķ”¢ÕēŹĶ╝®ÕģČĶĆ│ńø«Õø║µ£ēńøĖķŚ£ńäēĶĆģõ╣¤. (p.221).

82) Õøøµø░ńÜĘĶł×õ║║µēŹÕĮŖÕŁĖµ£āõ╣ŗÕ║ŵø░µ¼▓ķ¢ŗµ░æµÖ║Õģłķ¢ŗń┤│µÖ║µŁżµÄĪµ£¼õ╣ŗĶć│Ķ©Ćõ╣¤Ķæóµ░æõ╣ŗÕēćÕéÜĶ”¢ń┤│ĶæŻÕŠīńö¤õ╣ŗĶ¦Ćµæ®Ķ”¢ÕēŹĶ╝®ÕģČĶĆ│ńø«Õø║µ£ēńøĖķŚ£ńäēĶĆģõ╣¤õ╗ŖµøĖń▒ŹµŁŻń¤ŻĶ®”µ│Ģµö╣ń¤ŻĶĪ╣ÕÅ»õ╗źÕŠģÕż½µĢĖńÖŠÕŹāĶɼõ╣ŗõŠüõŠüĶĪŠń║ōĶĆīķĆÜõ╗Ģń▒Źõ╣ŗµē┐ĶŠ©ĶĪīĶĄ░ÕĆÖĶŻ£Ķ©ōµĢÖĶ½ĖÕōĪńÖ╗ń¦æÕåīõ╣ŗķĆ▓õ╗ĢÕē»µ”£Ķłēõ║║ń¦ĆµēŹõ╗źÕÅŖÕ░Ŗńö¤Õ╗Ģńö¤ÕŁĖńö¤Ķ½Ėõ║║ńīȵ£¬µ£ēõ╗źµō┤Õģģµ¢░Ķü×ķŚĪńÖ╝µ¢░ńÉåĶĆīõĮ┐õ╣ŗõĖƵ¢░õĖŹÕ╣Šµ¢╝ĶłŖńĢīµ¢░ńĢīõĖżńøĖµÆ×ńüŠõ╣Ä? (pp.221-222).

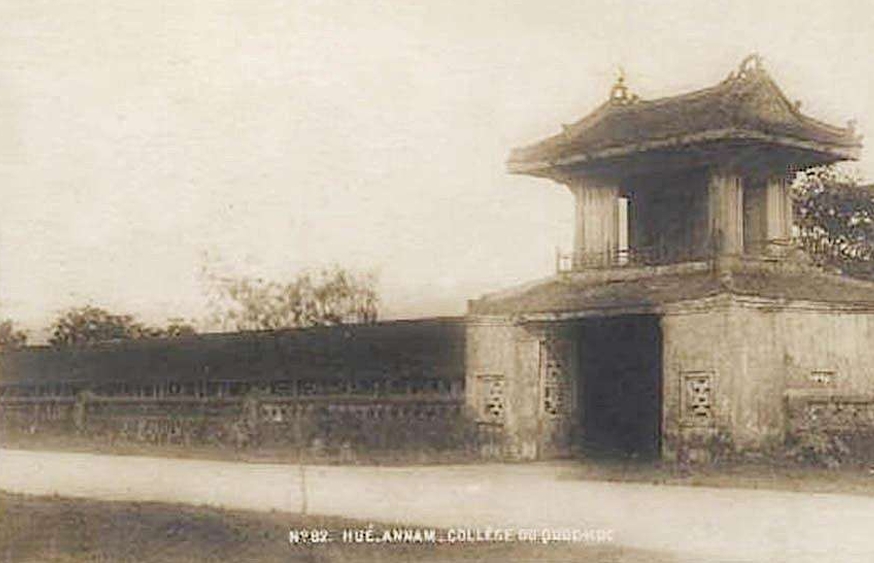

83) In the reign of King Gia Long of the Nguyß╗ģn Dynasty, the Imperial Academy was founded in Huß║┐ in 1803 under the name of ─Éß╗æc Hß╗Źc ─ÉŲ░ß╗Øng ńØŻÕŁĖÕĀé. It was renamed Quß╗æc Tß╗Ł Gi├Īm Õ£ŗÕŁÉńøŻ in March 1820 under the reign of King Minh Mß║Īng. An article by Robert de La Susse, titled ŌĆ£LŌĆÖEnseignement en AnnamŌĆØ (Education in Annam) printed in Les Annales Coloniales (June 03, 1913), also shows that French education had been introduced in this imperial institution around the time of its publication, ŌĆ£In addition, there is a special third-grade school in Hue called College Quß╗æc Tß╗Ł Gi├Īm. Quß╗æc Tß╗Ł Gi├Īm is the Vietnamese Prytan├®e; it receives the sons of royal or princely families and the children of the mandarins. There also modernism begins to do its work, and in the pagoda where the young Vietnamese used to learn exclusively the [Chinese] characters, the word of a French master comes today to be heard. The fact that French lessons are not the least assiduously attended is the best proof of the success of our teaching.ŌĆØ (p.2).

85) Kenichi Ohno. ŌĆ£Meiji Japan: Progressive Learning of Western TechnologyŌĆØ in Arkebe Oqubay and Kenichi Ohno, eds., How Nations Learn: Technological Learning, Industrial Policy, and Catch-up, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), p.91 ŌĆ£On top of all this, education became a national fad from top samurai to commoners. For adults, official and private courses were offered in ancient Chinese literature and philosophy as well as, in later years, Western languages, medicine, and navigation. For children aged roughly seven to thirteen, around twenty thousand unregulated for-profit private primary schools (terakoya) emerged all over Japan where self-appointed teachers taught reading, writing, and arithmetic (abacus) with flexible and individualized curriculums.ŌĆØ.

86) Eddie Guan, ŌĆ£The Domino Effect: Abolishing the Imperial Examination System and the Downfall of the Qing Dynasty,ŌĆØ The National High School Journal of Science (2023): 5-6, accessible at https://nhsjs.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/The-Domino-Effect-Abolishing-the-Imperial-Examination-System-and-the-Downfall-of-the-Qing-Dynasty.pdf: ŌĆ£To guarantee a smooth transition from the old to the new system, the Qing government established a reward system for those who were willing to study abroad. The government adopted a set of guidelines proposed by the Viceroy of Huguang Zhang Zhidong: ŌĆśStudents who receive a high school diploma or attend school for 8 years will be given the title of ŌĆ£jurenŌĆØ (equivalent to the second rank in Chinese scholar degree standard). Students who receive an undergraduate degree will be given the title of jinshi (equivalent to the first rank).ŌĆØ

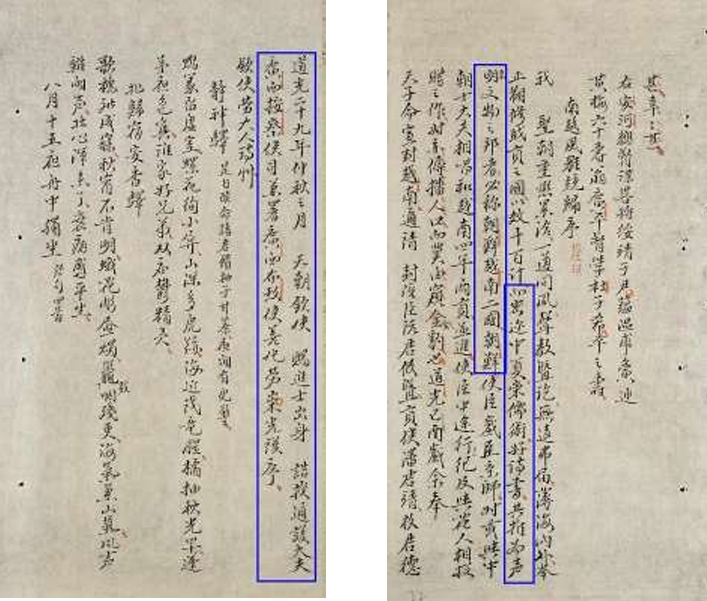

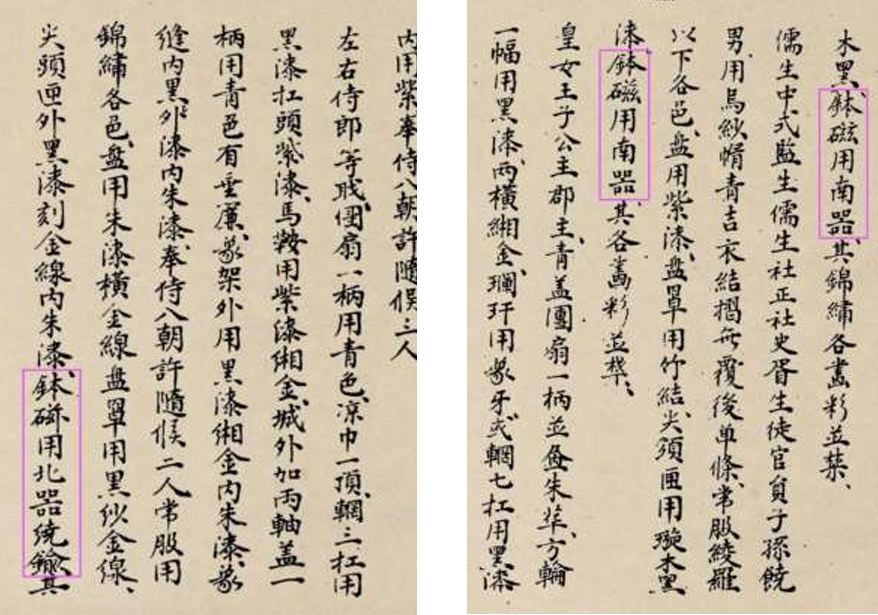

88) This account is from the multivolume encyclopedic work titled Lß╗ŗch Triß╗üu Hiß║┐n ChŲ░ŲĪng Loß║Īi Ch├Ł µŁĘµ£Øµå▓ń½ĀķĪ×Ķ¬ī (Categorized Records on Administrative Systems of Successive Dynasties of Vietnam) by Phan Huy Ch├║ µĮśĶ╝ص│© (1782-1840), compiled over ten years (1809-1819).

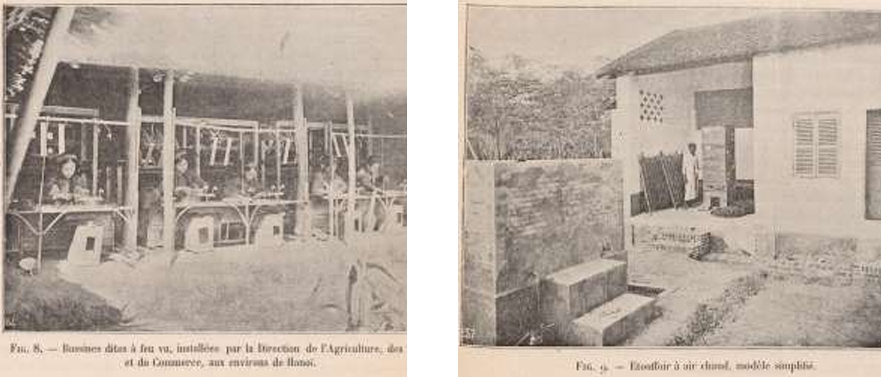

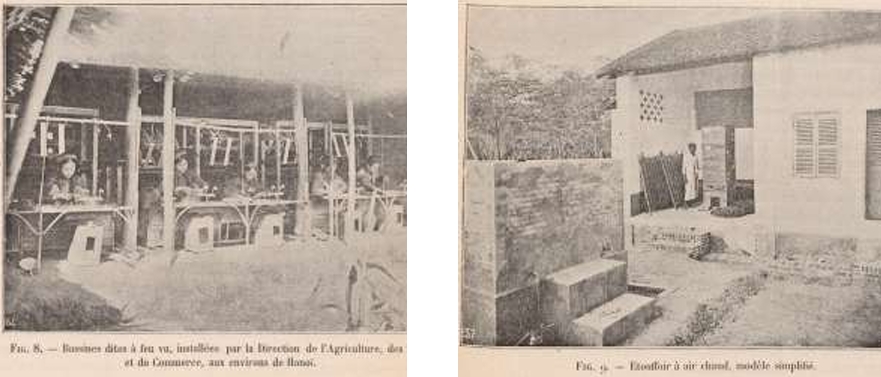

91) The Agricultural School (ŌĆ£TrŲ░ß╗Øng Canh N├┤ngŌĆØ or ŌĆ£Ecole dŌĆÖagricultureŌĆØ) was founded in Hue at the end of 1898 by Emperor Th├Ānh Th├ĪiŌĆÖs royal ordonnance. This agricultural school is ŌĆ£certainly among the number of works whose success would contribute the most, by training heads of indigenous culture, to facilitate the Europeans established in Annam the development of their agricultural holdings.ŌĆØ It is also interesting to learn about the schoolŌĆÖs first class of students, ŌĆ£At the beginning of the 1900-1901 school year, the choice was preferably made of former boys speaking and understanding French. This recruitment, however, only provided mediocre subjects, too old and fathers of family, having consequently occupations which prevented them from attending the courses regularly and fruitfully.ŌĆØ At this school, a variety of subjects were taught, such as general notions of botany, agriculture, arboriculture, vegetable growing, French language, and elementary arithmetic. Comit├® de lŌĆÖAsie fran├¦aise, ŌĆ£LŌĆÖ├ēcole dŌĆÖagriculture de Hu├®,ŌĆØ Bulletin du Comit├® de lŌĆÖAsie fran├¦aise ŌĆō Ann├®e (Paris: Comit├® de lŌĆÖAsie fran├¦aise, 1901), pp.26-27.

92) The Polytechnic School (ŌĆ£TrŲ░ß╗Øng B├Īch C├┤ngŌĆØ, literally ŌĆ£Ecole de cent m├®tiersŌĆØ or ŌĆ£School of one hundred m├®tiersŌĆØ) was established according to a royal ordonnance issued in the eleventh year of the reign of Emperor Th├Ānh Th├Īi (1899). In terms of its name, ŌĆ£The expression exceeded reality a little but it well characterized an establishment where we trained blacksmiths, farriers, fitters, turners, boilermakers, tinsmiths, molders-founders, carpenters, sculptors, masons, stonecutters, carvers, painters, saddlers, designers, etc.ŌĆØ Direction g├®n├®rale de lŌĆÖinstruction publique, Annam scolaire: De lŌĆÖenseignement traditionnel annamite ├Ā lŌĆÖenseignement modern franco-indig├©ne (Hanoi: Imprimerie dŌĆÖExtr├¬me-orient, 1931), p.133.

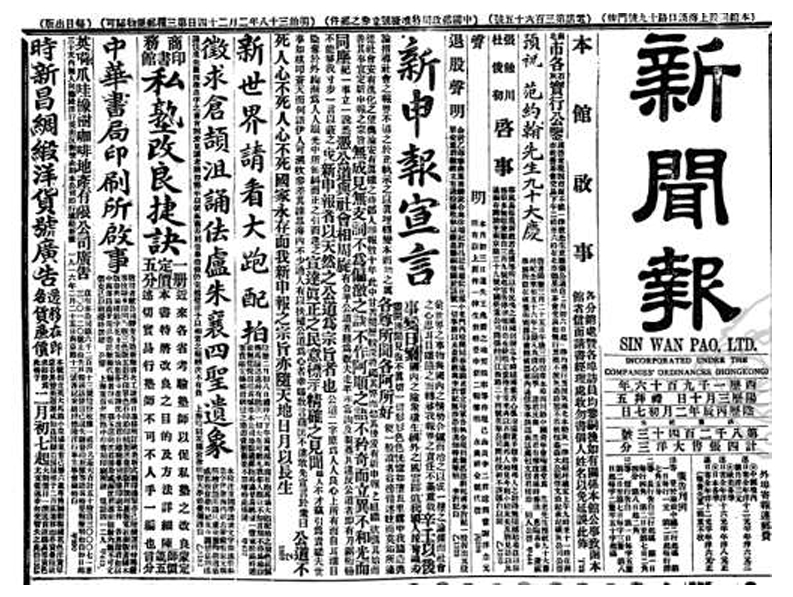

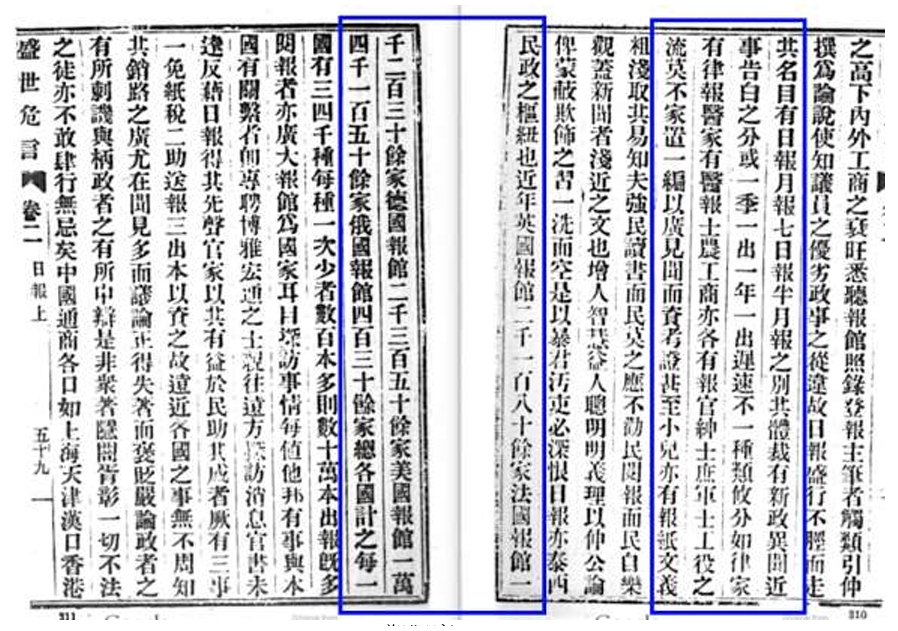

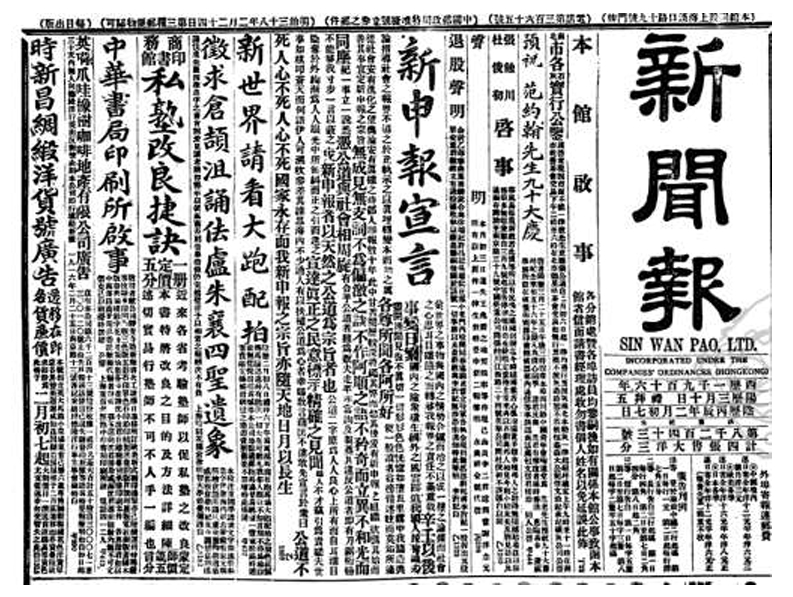

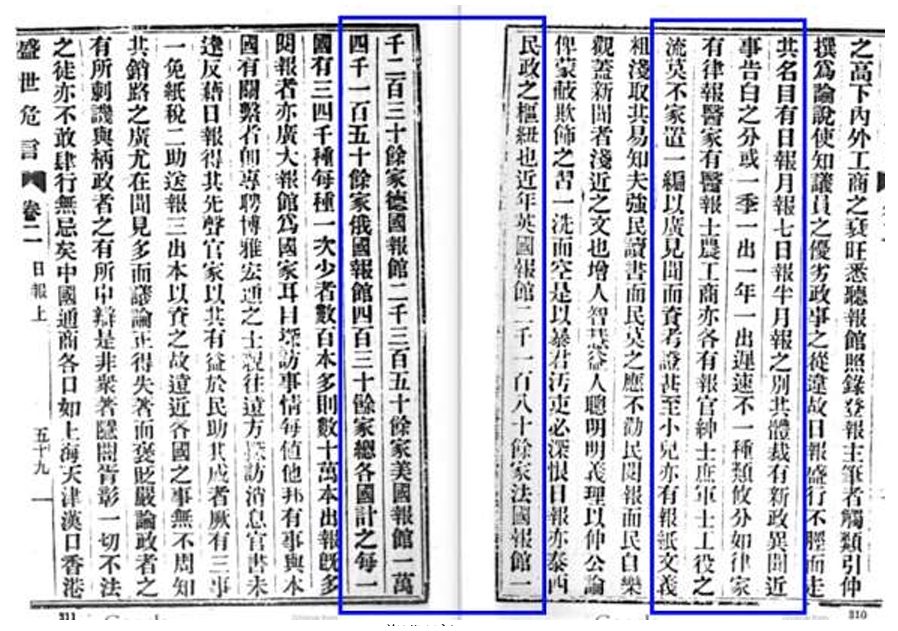

93) This long and informative paragraph is from chapter ŌĆ£Daily NewspaperŌĆØ (Ribao µŚźÕĀ▒) in Zheng GuanyingŌĆÖs ķäŁĶ¦Ćµćē (1842-1922) Shengshi weiyan zengding xinbian ńøøõĖ¢ÕŹ▒Ķ©ĆÕó×Ķ©éµ¢░ńĘ©’╝ł8ÕŹĘ’╝ē(Warnings to a Prosperous Age ŌĆō Updated New Edition), Guangxu gengzi ÕģēńĘÆÕ║ÜÕŁÉ edition (1900), reprinted by Taiwan Xuesheng shuju Ķć║ńüŻÕŁĖńö¤µøĖÕ▒Ć in 2 volumes(1965), pp.310-312.

94) Õż½!ÕĘźĶŚØõ╣ŗµ£ēķŚ£µ¢╝Õ£ŗÕ«Čõ╣¤Õż¦ń¤ŻµłæÕ╝ŚÕŗØõ║║õ║║Õ░浯ä.µłæĶ▓Īńö©µ╝ÅÕŹ«ĶĽµŁżńé║ńöÜõ╝╝Õ«£Õ╗ȵśÄÕĖ½Ķ│╝ÕäĆÕÖ©µōćķØłÕʦµ£ēµēŹĶĆģÕģģõ╣ŗõ╗źĶŠ░ńéżķĪ¦ĶĆīĶ©ōÕŗģõ╣ŗõĖŹõ╗żÕ£ŗõĖŁĶ½Ėµ£ēĶāĮÕŁĖÕŠŚµ¢░Õ╝ÅĶŻĮÕŠŚµ¢░ÕÖ©ĶĆģÕé▓µŁÉµ┤▓µö╗ńēīµåæńéżõ╣ŗõŠŗµ”«õ╣ŗõ╗źÕōüÕŠĪ,ÕÄÜõ╣ŗõ╗źÕ╗¬ń│łõ║łõ╣ŗõ╗źÕ░łÕł®Ķ½Ėµ£ēĶāĮµĀ╝Ķć┤µ░ŻÕī¢Ķ½ĖÕŁĖĶĆģÕģȵ”«Ķ▓┤Õć║Õż¦ń¦æõĖŖÕ”éµś»ĶĆīõĖŹĶĪÆÕʦńłŁÕźćõ╗źµ▒éÕŗØõ║║µ£¬õ╣ŗµ£ēõ╣¤. (pp.227-228)

95) See Ardath W. Burks, ŌĆ£The WestŌĆÖs Inreach: The Oyatoi Gaikokujin,ŌĆØ in The Modernizers ŌĆō Overseas Students, Foreign Employees, and Meiji Japan (Boulder and London: Westview Press, 1985), pp.187-206.

96) See W.J. Macpherson, Chapter 8 ŌĆ£Capital, Technology and EnterpriseŌĆØ in The Economic Development of Japan 1868-1941 (Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987), pp.64-69.

97) µ│ĢÕ£ŗõĖĆÕŹāõ║īńÖŠõĖēÕŹüķżśÕ«ČÕŠĘÕ£ŗõ║īÕŹāõĖēńÖŠõ║öÕŹüķżśÕ«ČĶŗ▒Õ£ŗõ║īÕŹāõĖĆńÖŠÕģ½ÕŹüķżśÕ«Čõ┐äÕ£ŗÕøøńÖŠõĖēÕŹüķżśÕ«ČńŠÄÕ£ŗõĖĆĶɼÕøøÕŹāõĖĆńÖŠõ║öÕŹüķżśÕ«ČµŚźµ£¼ńäĪķāĪõĖŹµ£ēÕĀ▒Ķłś. (p.228) This long and informative paragraph is from chapter ŌĆ£Daily NewspaperŌĆØ (Ribao µŚźÕĀ▒) in Zheng GuanyingŌĆÖs ķäŁĶ¦Ćµćē (1842-1922) Shengshi weiyan zengding xinbian ńøøõĖ¢ÕŹ▒Ķ©ĆÕó×Ķ©éµ¢░ńĘ©’╝łp.8 j.’╝ē(Warnings to a Prosperous Age ŌĆō Updated New Edition), Guangxu gengzi ÕģēńĘÆÕ║ÜÕŁÉ edition (1900), reprinted by Taiwan Xuesheng shuju Ķć║ńüŻÕŁĖńö¤µøĖÕ▒Ć in 2 volumes(1965), pp.310-312.

98) See Barbara Mittler, Chapter 6 ŌĆ£The Nature of Chinese Nationalism: Reading Shanghai Newspapers, 1900-1925ŌĆØ in A Newspaper for China? Power, Identity, and Change in ShanghaiŌĆÖs News Media, 1872-1912 (Cambridge & London: Harvard University Asia Center, 2004), pp.361-408.

100) ─Éß╗ōng v─ān is the shortened title of ─Éß║Īi Nam ─æß╗ōng v─ān nhß║Łt b├Īo Õż¦ÕŹŚÕÉīµ¢ćµŚźÕĀ▒ (─Éß║Īi Nam Newspaper in Shared Chinese Script, possibly initiated in 1891); see ─Éß╗Ś Quang HŲ░ng, Nguyß╗ģn Th├Ānh, and DŲ░ŲĪng Trung Quß╗æc. Lß╗ŗch sß╗Ł b├Īo ch├Ł Viß╗ćt Nam 1865-1945 (History of Vietnamese Newspapers 1865-1945)(Hanoi: ─Éß║Īi hß╗Źc Quß╗æc gia, 2000), p.40.

101) James L. Huffman, Creating a Public ŌĆō People and Press in Meiji Japan (Honolulu: University of HawaiŌĆÖi Press, 1997), p.226.

102) Alberta A. Altman, ŌĆ£The Press and Social Cohesion during a Period of Change: The Case of Early Meiji Japan,ŌĆØ Modern Asian Studies, vol. 15:4 (1981): 865-876.

110) Õ”éĶć¬ķ│┤ķÉśõ╣ŗµŹ®µ│ĢµóØĶĆīµ®¤Ķ╗ĖµéēĶć│ńäēÕģČÕÅ¢µĢłõ╣¤Õ”éջƵÜæķćØõ╣ŗµćēń®║µ░ŻĶĆīńĄ▓õ║│õĖŹÕĘ«ńäē. (p.234).

111) The printed text A.567 reads, µ¢ćµśÄĶĆģķØ×ÕŠÆĶ│╝õ╣ŗõ╗źÕā╣ÕĆ╝ĶĆīÕĘ▓ÕÅłĶ│╝õ╣ŗõ╗źĶŗ”ńŚø. This is a citation from Liang Qichao's µóüÕĢōĶČģ (1873-1929) article Shizhong Dexing Xiangfan Chengyi ÕŹüń©«ÕŠĘµĆ¦ńøĖÕÅŹńøĖµłÉńŠ® (The Complementary Theses and Antitheses of Ten Virtues, 1901), first printed under Liang's style-name Ren'gong õ╗╗Õģ¼ in Qingyi bao µĖģĶŁ░ÕĀ▒, no. 82, 5151-5157; no. 84, 5267-5273. Here Liang seemingly refers to what is discussed in John Stuart MillŌĆÖs (1806-1873) Civilization: ŌĆ£In the case, however, of the most influential classes ŌĆō those whose energies, if they had them, might be exercised on the greatest scale and with the most considerable result ŌĆō the desire of wealth is already sufficiently satisfied, to render them averse to suffer pain or incur much voluntary labor for the sake of any further increase, ŌĆ£ and ŌĆ£There has been much complaint of late years, of the growth, both- in the world of trade and in that of intellect, of quackery, and especially of puffing: but nobody seems to have remarked, that these are the inevitable fruits of immense competition.ŌĆØ John Stuart Mill. Collected Works of John Stuart Mill Vol. XVIII: Essays on Politics and Society (Toronto: University of Toronto, 1977), p.130 and 133.

112) The opening of Chapter ŌĆ£QiushuiŌĆØ ń¦ŗµ░┤ (Autumn Floods) in Zhuangzi ĶÄŖÕŁÉreads, ŌĆ£At the time of autumn floods when hundreds of streams poured into the Yellow River, the torrents were so violent that it was impossible to distinguish an ox from a horse from the other side of the river. Then the River God was overwhelmed with joy, feeling that all the beauty under heaven belonged to him alone. Down the river he travelled east until he reached the North Sea. Looking eastward at the boundless expanse of water, he changed his countenance and sighed to the Sea God, saying, ŌĆśAs the popular saying goes, ŌĆśThere are men who have heard a lot about Tao but still think that no one can surpass them.ŌĆÖ I am one of such men.ŌĆÖ µ£øµ┤ŗÕÉæĶŗźĶĆīÕśåµø░: 'ķćÄĶ¬×µ£ēõ╣ŗ, µø░: Ķü×ķüōńÖŠõ╗źńł▓ĶĽÕĘ▒ĶŗźĶĆģ, µłæõ╣ŗĶ¼éõ╣¤.ŌĆØ Zhuangzi, Zhuangzi ĶÄŖÕŁÉ, translated into English by Wang Rongpei µ▒¬µ”ĢÕ¤╣; translated into modern Chinese by Qin Xuqing ń¦”µŚŁÕŹ┐ and Sun Yongchang ÕŁ½ķøŹķĢĘ (Changsha, Hunan PeopleŌĆÖs Publishing House and Foreign Languages Press, 1999), p.261.

113) Huang Zunxian ķ╗āÕ░Ŗµå▓ (1848-1905) in his Reben guozhi µŚźµ£¼Õ£ŗÕ┐Ś (Treatises on Japan) writes, ŌĆ£The Unofficial Historian states that having the remainder to discuss Western statutes, the fact that their established instructions originate from Mozi Õó©ÕŁÉI have clearly talked about . Their application methods are similar to those of the legalists Shen Buhai ńö│õĖŹÕ«│ (395 BCE-337 BCE) and Han Fei ķ¤ōķØ× (280 BCE-233 BCE); the setup of their mandarin system similar to Zhouli Õæ©ń”« (Rites of the Zhou dynasty); their administration similar to what described in Guanzi ń«ĪÕŁÉ up to 7 or 8 out of 10. In regard to the studies of natural science, the knowledge is dispersed and can be found in a greater number in books from the Zhou Õæ© and Qin ń¦” dynasties. Having studied Western learning, IŌĆÖve found it in fact the learning from Mo Di Õó©ń┐¤ (470 BCE-319 BCE) 3-µŚźµ£¼Õ£ŗÕ┐Ś(õĖŗÕŹĘ)Õż¢ÕÅ▓µ░ŵŚź’╝Üõ╗źķżśĶ©ÄĶ½¢Ķź┐µ│Ģ, ÕģČń½ŗµĢÖµ║ɵ¢╝Õó©ÕŁÉ, ÕÉŠµŚóĶ®│Ķ©Ćõ╣ŗń¤Ż. ĶĆīÕģČńö©µ│ĢķĪ×õ╣Äńö│ķ¤ō, ÕģČĶ©ŁÕ«śķĪ×õ╣ÄÕæ©ń”«, ÕģČĶĪīµö┐ķĪ×õ╣Äń«ĪÕŁÉĶĆģ, ÕŹüĶōŗõĖāÕģ½. ĶŗźÕż½õĖĆÕłćµĀ╝Ķć┤õ╣ŗÕŁĖ, µĢŻĶ”ŗµ¢╝Õæ©ń¦”Ķ½ĖµøĖĶĆģÕ░żÕżÜ. õĮÖĶĆāµ│░Ķź┐õ╣ŗÕŁĖ, Õó©ń┐¤õ╣ŗÕŁĖõ╣¤.

114) The printed Chinese text reads, Ķ¢äµĄĘÕģ¦Õż¢µÄ©ńé║Ķü▓ÕÉŹµ¢ćńē®õ╣ŗķé”. Once considered to be a citation from Lao Chongguang, this is in fact a corrupt quote: its first half is from another sentence praising ChinaŌĆÖs administrative principles that were observed by its neighboring and far-distant counterparts, Ķ¢äµĄĘÕģ¦Õż¢, whereas the second half is not only for Vietnam. Lao ChongguangŌĆÖs original sentence reads, ŌĆ£Located near the Chinese Middle Kingdom, Korea and Vietnam must be named as the states advocating Confucianism and greatly admiring Confucian classics, and both being promoted to the appellation of the ŌĆśrealms of famous historical relicsŌĆÖŌĆØ Õ»åķéćõĖŁÕżÅ, Õ┤ćÕäÆĶĪōÕźĮĶ®®µøĖ, Õģ▒µÄ©ńé║Ķü▓ÕÉŹµ¢ćńē®õ╣ŗķé”, Õ┐ģń©▒µ£Øķ««┬ĘĶČŖÕŹŚõ║īÕ£ŗ. An eminent scholar whose score in the jinshi examination was impressively high, Lao Chongguang (1802-1867) served as ŌĆ£the Qing inspector general and later governor-general to Guangdong Õ╗ŻµØ▒ and Guangxi Õ╗ŻĶź┐ along the Vietnamese border from 1852ŌĆØ Kathlene Baldanza, ŌĆ£Books without Borders: Phß║Īm Thß║Łn Duß║Łt (1825-1885) and the Culture of Knowledge in Mid-Nineteenth-Century VietnamŌĆØ, Journal of Asian Studies vol. 77, no. 3 (2018): 728-729. Extant copies of LaoŌĆÖs preface can be found in Tß║Łp mß╗╣ thi v─ān ķøåńŠÄĶ®®µ¢ć (Collection of Literary Delicacies, preserved in the Han-Nom Research InstituteŌĆÖs Library, A.2987), Nhß║Łt Nam phong nh├Ż thß╗æng bi├¬n µŚźÕŹŚķó©ķøģńĄ▒ńĘ© (Edited Collection of Nhß║Łt Nam's Airs and Odes Poetry, Han-Nom library, A.2822), or in a handwritten copy of verse and prose with no title but headed by a piece of writing called Ķ¼Øµ×ŚõŠŹķāÄńł▓ĶłēÕĢ¤ A Memorial Expressing Gratitude to Vice Minister L├óm For the Promotion (accessible online at: https://lib.nomfoundation.org/collection/1/volume/575/page/77) For Lao ChongguangŌĆÖs interactions with Vietnamese envoys and officials, see Liu Yujun ÕŖēńÄēńÅ║, ŌĆ£Vietnamese Envoys and Sino-Vietnamese ExchangesŌĆØ ĶČŖÕŹŚõĮ┐ĶćŻĶłćõĖŁĶČŖµ¢ćÕŁĖõ║żµĄü, Xueshu Yanjiu ÕŁĖĶĪōńĀöń®Č no. 1 (2007): 146.

115) The phonetic transcription of Wate ńō”Õ┐Æ for James Watt appears to be a mixed result of two different ways to transcribe his name into Chinese, one is Huate ĶÅ»Õ┐Æ, as seen in Kang YouweiŌĆÖs ŌĆ£Ruidian youjiŌĆØ ńæ×ÕģĖķüŖĶ©ś (Sweden Travelogue) and the more popular one Wate ńō”ńē╣.

116) Aidisun/Ai ─æß╗ŗch t├┤n ÕōĆńŗäÕŁ½ is the way Ding WeiliangõĖüķ¤ÖĶē» (William Alexander Parsons Martin, 1827-1916) transcribed the name of Edison into Chinese. See Fu Deyuan ÕéģÕŠĘÕģā, Ding Weiliang and Modern Cultural Exchanges between China and the West õĖüķ¤ÖĶē»ĶłćĶ┐æõ╗ŻõĖŁĶź┐µ¢ćÕī¢õ║żµĄü (Taibei, Guoli Taiwan daxue chuban zhongxin, 2013), p.385.

117) In an essay titled ŌĆ£On NewspapersŌĆÖ Benefits to National AffairsŌĆØ Ķ½¢ÕĀ▒ķż©µ£ēńøŖµ¢╝Õ£ŗõ║ŗ (August 9, 1896), Liang Qichao argues that, ŌĆ£WesternersŌĆÖ major newspapers are the place where the parliamentŌĆÖs discussions are recorded (ŌĆ”) Since newspapersŌĆÖ benefits to national affairs are as such, talent and virtuous scholars could be their editors-in-chief in the past, and now become administrators of the government. There are also those who retired from government business in the morning, and enter the newspaper publishing house in the evening, being responsible for the state policy.ŌĆØ Ķź┐õ║║õ╣ŗÕż¦ÕĀ▒õ╣¤, ĶŁ░ķÖóõ╣ŗĶ©ĆĶ½¢ń┤Ćńäē (ŌĆ”) ÕģČńøŖµ¢╝Õ£ŗõ║ŗÕ”éµŁż, µĢģµćʵēŹµŖ▒ÕŠĘõ╣ŗÕŻ½, µ£ēµś©ńé║õĖ╗ńŁåĶĆīõ╗ŖõĮ£Õ¤Ęµö┐ĶĆģ, õ║”µ£ēµ£ØńĮʵ©×Õ║£ĶĆīÕżĢķĆ▓ÕĀ▒ķż©ĶĆģ, ÕģČõĖ╗Õ╝ĄÕ£ŗµś», µ»ÅĶłćµö┐Õ║£ķĆÜĶü▓µ░Ż.

118) Both the printed A.567 and the hand-copied R.287 have it as Binsisai Ķ│ōµ¢»ÕĪ×. It should be correctly spelled out as Sibinsai µ¢»Ķ│ōÕĪ× (Spencer).

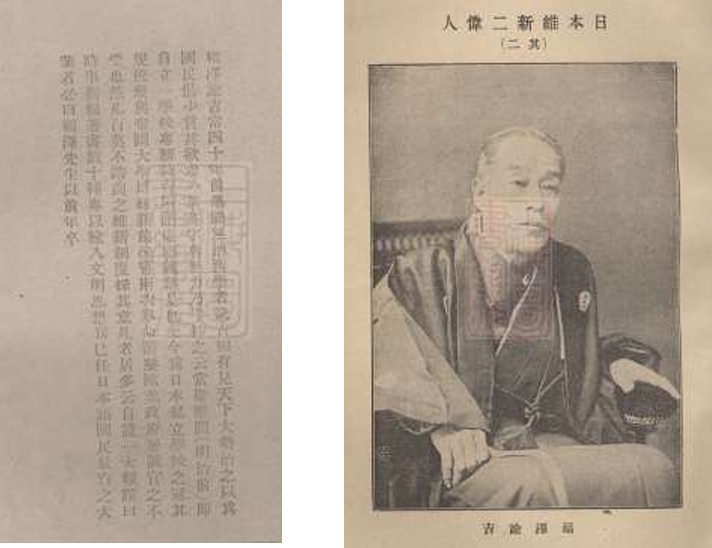

119) Liang QichaoŌĆÖs essay ŌĆ£On the WorldŌĆÖs Power of KnowledgeŌĆØ Ķ½¢ÕŁĖĶĪōõ╣ŗÕŗóÕŖøÕĘ”ÕÅ│õĖ¢ńĢī, first published in ŌĆ£HuibianŌĆØ ÕĮÖńĘ© of Xinmin Congbao in 1900 with no Western names written alphabetically, 35-48, and reprinted on no. 1, 1902, 69-78 lists a number of most influential Western scientists, explorers, politicians, and thinkers, such as Gebaini ÕōźńÖĮÕ░╝ (Nicolaus Copernicus, 1473-1453), Mazhilun ńæ¬Õ┐ŚõŠ¢ (Ferdinand Magellan, 1480-1521), Mengde siqiu ÕŁ¤ÕŠĘµ¢»ķ│® (Montesquieu, 1689-1755), Lusuo ńø¦µóŁ(Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 1712-1778), Fulankeling Õ»īĶśŁÕģŗõ╗ż (Benjamin Franklin, 1706-1790), Yadan simi õ║×õĖ╣ŌĆóµ¢»Õ»å (Adam Smith, 1723-1790), Bolunzhili õ╝»ÕĆ½ń¤źńÉå (Johann Kaspar Bluntschli, 1808-1881), or Daerwen ķüöńłŠµ¢ć (1809-1882). It is also worth mentioning that at the end of the essay, Liang wrote, ŌĆ£There have been also people who unnecessarily advocated new theories, but thanks to their sincere spirit, noble thoughts, splendid words, could transmit the new ideas of civilization from other countries, and implement them in their own countries in order to bring benefit to their compatriots. The power of those people is also great and unimaginable.ŌĆØ õ║”µ£ēõĖŹÕ┐ģĶć¬Õć║µ¢░Ķ¬¬, ĶĆīõ╗źÕģČĶ¬Āµććõ╣ŗµ░Ż, µĖģķ½śõ╣ŗµĆØ, ńŠÄÕ”Öõ╣ŗµ¢ć, ĶāĮķüŗõ╗¢Õ£ŗµ¢ćµśÄ µ¢░µĆصā│, ń¦╗µżŹµ¢╝µ£¼Õ£ŗ, õ╗źķĆĀń”ŵ¢╝ÕģČÕÉīĶā×, µŁżÕģČÕŗóÕŖø, õ║”Ķżćµ£ēÕüēÕż¦ĶĆīõĖŹÕÅ»µĆØĶŁ░ĶĆģ. In the list of such outstanding characters, was Fukuzawa Yukichi ń”ŵ▓óĶ½ŁÕÉē cited among other Western thinkers, such as Fuluteer ń”Åńź┐ńē╣ńłŠ (Voltaire, 1694-1778), or Tuoersitai Ķ©ŚńłŠµ¢»µ│░ (Tolstoy). For Fukuzawa, Liang adds a note ŌĆ£qunian zu ÕÄ╗Õ╣┤ÕŹÆŌĆØ (died last year, i.e., 1901). In the same year (1902), under the title ŌĆ£Two Great Persons of JapanŌĆÖs ReformsŌĆØ µŚźµ£¼ńČŁµ¢░õ║īÕüēõ║║, Xinmin Congbao presented two portraits of Saig┼Ź Takamori Ķź┐ķäĢķÜåńøø (1828-1877) and Fukuzawa Yukichi together with their short biographies. As for Fukuzawa, his biography clearly points out him as the advocator of Western studies, and the founder of Kei┼Ź gijuku µģȵćēńŠ®ÕĪŠ, which was at that time, the top among private schools in Japan.ŌĆØ (no. 7, p. 15). As an obituary composed for the passing of Herbert Spencer, the article ŌĆ£A Short Biography of the Great Philosopher SpencerŌĆØ Õż¦Õō▓µ¢»Ķ│ōÕĪ×ńĢźÕé│ŌĆØ indicates that even though Darwin initiated the theory of evolution, it was fully developed by Spencer (Xinmin Congbao, ŌĆ£Huibian ÕĮÖńĘ©ŌĆØ, 1903, p. 447. It should also be noted that in the early twentieth century, a series of introductory research on Spencer by Japanese scholar Aruga Nagao µ£ēĶ│ĆķĢĘķøä was translated into Chinese, which identified Spencer with the theory of evolution, for instance Theory of Evolution for the Common Herd õ║║ńŠżķĆ▓Õī¢Ķ½¢, translated by Shunde Mai Zhonghua ķĀåÕŠĘķ║źõ╗▓ĶÅ» (Shanghai, Guangzhi shuju, 1903). See also Han Chenghua ķ¤ōµē┐µ©║, ŌĆ£Spencer Reaching China: A Historical Translation DiscussionŌĆØ µ¢»Ķ│ōÕĪ×Õł░õĖŁÕ£ŗ: õĖĆÕĆŗń┐╗ĶŁ»ÕÅ▓ńÜäĶ©ÄĶ½¢, Bianyi luncong ńĘ©ĶŁ»Ķ½¢ÕÅóvol. 3, no.2 (2010): 42.

As for Montesquieu, a record named ŌĆ£A Memorandum from Huang ZunxianŌĆØ µØ▒µĄĘÕģ¼õŠåń░Ī, published in Xinmin Congbao, vol. 13 (1902), reports that, ŌĆ£Around the twelfth or thirteenth year of the Meiji reign(1879 or 1880), the theory of peopleŌĆÖs rights reached its zenith. I was quite surprised when first hearing about it. Having chosen Rousseau and MontesquieuŌĆÖs theories to read, my mind changed immediately." µśÄµ▓╗ÕŹüõ║īõĖēÕ╣┤µ░æµ¼Ŗõ╣ŗĶ¬¬µźĄńøø. ÕłØĶü×ķĀŚķ®ÜµĆ¬┬ʵŚóĶĆīÕÅ¢ńø¦µóŁ┬ĘÕŁ¤ÕŠĘµ¢»ķ│®õ╣ŗĶ¬¬Ķ«Ćõ╣ŗ┬ĘÕ┐āÕ┐Śńé║õ╣ŗõĖĆĶ«Ŗ. Thus, minquanpian/d├ón quyß╗ün thi├¬n µ░æµ¼Ŗń»ć in the VMTHS should not be taken as MontesquieuŌĆÖs work, but his trend of thought.

120) In his essay "Shizhong dexing xiangfan chengyiŌĆØ (op. cit.), after briefly describing the development of the republic system Õģ▒ÕÆīµö┐ķ½ö of the United States, Liang Qichao introduces FranceŌĆÖs political regime, ŌĆ£In France, since the Great Revolution of 1789, the two Republic and Monarchical parties have mutually gone up and down over half a century, but up until now, peopleŌĆÖs rights in France remain incomparable to those of Britain and America.ŌĆØ µ│ĢÕ£ŗÕēćĶć¬õĖĆõĖāÕģ½õ╣ØÕ╣┤Õż¦ķØ®ÕæĮõ╗źÕŠī, ÕÉøµ░æÕģ®ķ╗©, õ║ÆĶĄĘõ║Æ õ╗å, Õ×éÕŹŖõĖ¢ń┤Ćķżś, ĶĆīĶć│õ╗Ŗµ░æµ¼Ŗõ╣ŗńøøńīČõĖŹÕÅŖĶŗ▒ńŠÄĶĆģ. Nishimura Shigeki Ķź┐µØæĶī鵩╣ also talks about ŌĆ£DictatorshipŌĆØ õ║║ÕÉøńŹ©ĶŻü, ŌĆ£Rule Shared by the King and the PeopleŌĆØ ÕÉøµ░æÕÉīµ▓╗, and ŌĆ£Civilian RepublicŌĆØ Õ╣│µ░æÕģ▒ÕÆī. Nishimura Shigeki, Discussion on Three Political Systems µö┐ķ½öõĖēń©«Ķ¬¬, Meiroku zasshi no. 28 (1875), recited from Zhang Yunqi Õ╝ĄÕģüĶĄĘ, ed. Historical Documents of Japanese Law and Politics in the early Meiji Period µŚźµ£¼µśÄµ▓╗ÕēŹµ£¤µ│Ģµö┐ÕÅ▓µ¢Ö (Beijing: Qinghua daxue chubanshe, 2016), p.91.

121) Youwu/Hß╗»u v├Ą ÕÅ│µŁ” (Honoring the military) is a term Liang Qichao employed in an essay called ŌĆ£ChinaŌĆÖs Way of WarriorsŌĆØ õĖŁÕ£ŗõ╣ŗµŁ”ÕŻ½ķüōŌĆØ; see https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&res=548363.

122) In an essay titled ŌĆ£On the Age of TransitionŌĆØ ķüÄÕ║”µÖéõ╗ŻĶ½¢, in Yinbingshi ķŻ▓Õå░Õ«żÕÉłķøå (1901), Liang Qichao reserved a section called ŌĆ£Characters of the Age of Transition and Their Indispensable VirtuesŌĆØ ķüÄÕ║”µÖéõ╗Żõ╣ŗõ║║ńē®ĶłćÕģČÕ┐ģĶ”üõ╣ŗÕŠĘµĆ¦, in which he pointed out three required virtues: adventurous ÕåÆķܬµĆ¦, patient Õ┐ŹĶĆɵƦ, and discriminately selecting ÕłźµōćµĆ¦. MosesŌĆÖ travel to Canaan, and ColumbusŌĆÖ adventure in the Atlantic were mentioned in this essay. See https://shorturl.at/zKRR6 Italian Jesuit priest Matteo Ricci first arrived at Macau in 1582 and spent the rest of his life in China until 1610 when he passed away in Beijing. Xinmin Congbao also discusses Matteo RicciŌĆÖs case in a few articles, such as ŌĆ£A Brief History of Natural SciencesŌĆ£ µĀ╝Ķć┤ÕŁĖµ▓┐ķØ®ĶĆāńĢź, no. 14 (1902): 9-17; or ŌĆ£The Eastward Movement of Western Religions during the Tang DynastyŌĆØ ÕöÉõ╗ŻĶź┐µĢÖõ╣ŗµØ▒µ╝Ė, vol. 3, no. 9 (1904): 37-46.

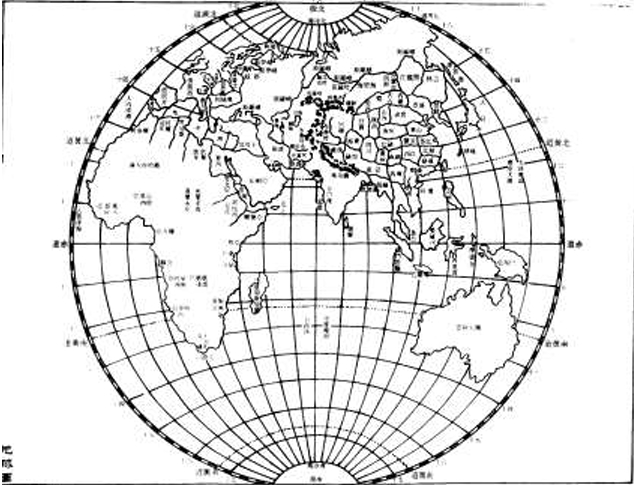

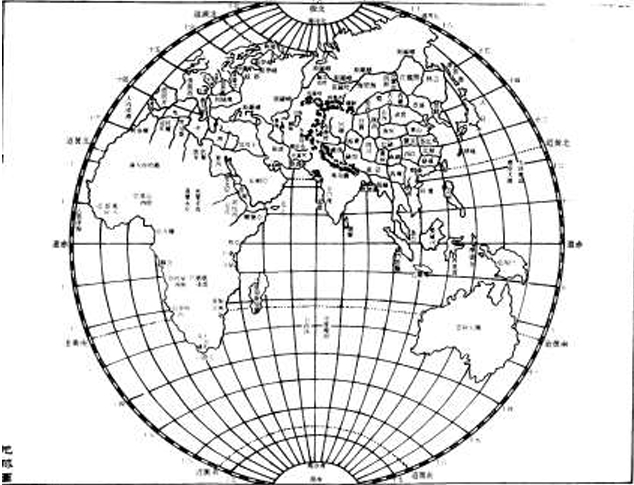

123) The VMTHS only reads as binghai/b─āng hß║Żi Õå░µĄĘ (glaciomarine) without specifically identifying it as Arctic or Antarctic Oceans. Xu JisheŌĆÖs ÕŠÉń╣╝ńĢ¼ (1795-1873) section called ŌĆ£Diqiu Õ£░ńÉāŌĆØ (The Globe) in Concise Records of the World ńĆøÕ»░Õ┐ŚńĢź reports an interesting account of how Chinese people learned about the existence of Arctic and Antarctic Oceans: ŌĆ£Arctic Ocean is what everyone had known, but people had not been aware of Antarctic Ocean. When reading the map of the globe drawn by Westerners, and finding a note stating ŌĆśAntarctic OceanŌĆÖ down at Antarctica, people thought that due to their limited knowledge of Chinese language, the Westerners mistakenly named it based on the Arctic Ocean.ŌĆØ ÕīŚÕå░µĄĘõ║║õ║║ń¤źõ╣ŗ, ÕŹŚÕå░µĄĘµ£¬õ╣ŗÕēŹĶü×, ķĀāķ¢▒Ķź┐µ┤ŗõ║║µēĆń╣¬Õ£░ńÉāÕ£¢, µ¢╝ÕŹŚµźĄõ╣ŗõĖŗ, µ│©µø░ ÕŹŚÕå░µĄĘ, õ╗źńé║õĖŹķĆÜĶÅ»µ¢ć, Ķ¬żõ╗źÕīŚÕå░µĄĘõŠŗń©▒õ╣ŗõ╣¤.

124) Kang Youwei discusses zhimin zhi xue µ«¢µ░æõ╣ŗÕŁĖ (Colonial studies/Colonialism) in a travel diary called ŌĆ£Concise Records of the WorldŌĆØ ÕŹ░Õ║”ķüŖĶ©ś (1901), ŌĆ£Besides the ancients, starting from the two dynasties of Sui ķÜ© (581ŌĆō618), and YuanŌĆÖs Õģā (1279ŌĆō1368) conquers of Java, or the expansion down to the South Seas by Zheng He ķäŁÕÆī (1371-1433) of the Ming dynasty, rarely have any other cases existed. China has stuck to old ways of thought and allowed very few changes; it did not talk about colonial studies/colonialism, but set up prohibitions on maritime trade with foreign countries, and consequently, sit still and yielded the South Seas to others.ŌĆØ ÕÅżĶĆģĶć¬ķÜ©┬ĘÕģāÕģ®µ£ØÕŠüńō£Õōć┬ʵśÄķäŁõĖēÕ»ČõĖŗÕŹŚµ┤ŗÕż¢┬Ęķ««µ£ēķüÄõ╣ŗ. õĖŁÕ£ŗµ│źÕÅżÕ░æĶ«Ŗ┬ĘõĖŹĶ¼øµ«¢µ░æõ╣ŗÕŁĖ┬Ęõ╣ģĶ©ŁµĄĘń”ü┬ʵĢģÕØÉõ╗źÕŹŚµ┤ŗõ╣ŗÕ£░Ķ«ōõ║║õ╣¤.ŌĆØ See Kang Youwei Õ║ʵ£ēńé║, Travelogues through Various Countries ŌĆō Kang YouweiŌĆÖs Posthumous Manuscripts ÕłŚÕ£ŗķüŖĶ©śŌĆöŌĆöÕ║ʵ£ēńé║ķü║ń©┐ (Shanghai: Shanghai Renmin chubanshe, 1995), p.2. In the early twentieth century, colonialism became attractive to East Asian countries, such as China, as a way to strengthen the nation and to join the world of civilization. Thus, even though not directly using the term zhimin (zhi) xue µ«¢µ░æ(õ╣ŗ)ÕŁĖ, Liang Qichao promoted colonial studies/colonialism in a number of essays. For instance, in section fifteen called ŌĆ£On Untiring EffortsŌĆØ Ķ½¢µ»ģÕŖø of Discourse on the New Citizen µ¢░µ░æĶ¬¬ published in Xinmin Congbao in 1902, Liang Qichao wrote, ŌĆ£HavenŌĆÖt you seen the case of Britain? Since Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) took commercial colonization as the state policy, a few hundreds of years later, it has been following it without any step back.ŌĆØ õĖŹĶ¦ĆĶŗ▒Õ£ŗõ╣Ä’╝¤Ķć¬Õģŗµ×ŚÕ©üńłŠõ╗źõŠåõ╗źķĆÜÕĢ嵫¢µ░æńé║Õ£ŗµś»┬ĘńłŠÕŠīµĢĖńÖŠÕ╣┤õĖŹõĖĆķĆĆĶĮē. see https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=634263&remap=gb. In another work titled ŌĆ£The Biographies of Eight Great Colonialists from ChinaŌĆØ õĖŁÕ£ŗµ«¢µ░æÕģ½Õż¦Õüēõ║║Õé│ (1905), through the biographies, Liang provides eight accounts of ChinaŌĆÖs colonial history realized in Sumatra, Philippines Island, Java Island, Borneo Island, Myanmar, Vietnam, Siam, Malaysia Peninsula; see https://shorturl.at/J1Tan.

125) Huanghua fengyu/Ho├Āng hoa phong v┼® ķ╗āĶŖ▒ķó©ķø© are two symbolic images often found in Li QingzhaoŌĆÖs µØĵĖģńģ¦ (1084-1156) poetry. A female poet and essayist of the Song Dynasty, Li employed chrysanthemum and winds and rains to express what happens in both the external and internal worlds. Basically, the combination of the symbolic chrysanthemum and winds-and-rains in the expression huanghua fengyu shows both the physical and spiritual sufferings. See Wu Zhongyun ÕÉ│Õ┐ĀĶĆś. ŌĆ£The Life Connotation of ŌĆ£ChrysanthemumŌĆØ and ŌĆ£Wind and RainŌĆØ in Li QingzhaoŌĆÖs PoemŌĆØ µØĵĖģńģ¦Ķ»ŹõĖŁ ŌĆ£ķŻÄķø©ŌĆ£┬ĘŌĆØķ╗äĶŖ▒ŌĆ£µäÅĶ▒ĪńÜäńö¤ÕæĮÕåģµČĄ, Mianyang shifan xueyuan xuebao, vol. 30, no. 12 (2011): 38-41.

126) Chunqiuµśźń¦ŗ(Spring and Autumn Annals) points out the way of thought in distinguishing ŌĆ£interiorŌĆØ from ŌĆ£exteriorŌĆØ within ancient states, especially between Xia ÕżÅ and the others in early China, ŌĆ£To regard oneŌĆÖs own state as interior and all the Xia as exterior, to regard all the Xia as interior and the Yi-Di as exterior.ŌĆØ ÕÅłÕģ¦ÕģČÕ£ŗĶĆīÕż¢Ķ½ĖÕżÅ┬ĘÕģ¦Ķ½ĖÕżÅĶĆīÕż¢ÕżĘńŗä. Yuri Pines, Paul R. Goldin, and Martin Kern, eds. Ideology of Power and Power of Ideology in Early China (Leiden: Brill, 2015): p.113. In a preface titled ŌĆ£Chunqiu Zhongguo YiDi bian xuŌĆØ µśźń¦ŗõĖŁÕ£ŗÕżĘńŗäĶŠ»Õ║Å published in Shiwu bao µÖéÕŗÖÕĀ▒ (August 18, 1897), written for Xu QinŌĆÖs ÕŠÉÕŗż On ChinaŌĆÖs Concept of Yi-Di õĖŁÕ£ŗÕżĘńŗäĶŠ», Liang Qichao tried to prove that there was no geographical and racist discriminations. In later dynasties, when China was placed at the center and other states surrounding it were named accordingly to their directional relationship to the center as Northern Di ńŗä, Eastern Yi ÕżĘ, Southern Man ĶĀ╗, or Western Rong µłÄ, ŌĆ£Inner Civilized, Outer BarbarianŌĆØ Õģ¦ÕżÅÕż¢ÕżĘ, it was practiced not only by the Middle Kingdom, but also its neighboring states, including Vietnam (which, in its turn, put itself at the center as civilized, and treated its Southern bordering states as barbarians). However, the thought of ŌĆ£inner civilized, outer barbarianŌĆØ was strikingly challenged when China witnessed the transition between Ming and Qing dynasties, and later, when this country and other East Asian nations were facing Western civilization. During the transitional period of the Ming and Qing dynasties, there appeared the topic of Changing Conditions of Chinese and Barbarians ĶÅ»ÕżĘĶ«Ŗµģŗ initiated by Japanese Hayashi Harukatsu µ×ŚµśźÕŗØand Hayashi Nobuatsuµ×Śõ┐Īń»ż in their work with the same title (1732), describing the dramatic changes from ŌĆ£civilizedŌĆØ to ŌĆ£barbarianŌĆØ of the HuaXia ĶÅ»ÕżÅ. The critical review of the thought ŌĆ£inner civilized, outer barbarianŌĆØ reflected in VMTHS more or less appears close to the kai hentai.

128) Chapter ŌĆ£QishiŌĆØ ķĮŖõĖ¢ in Wang ChongŌĆÖs ńÄŗÕģģ (27 ŌĆō100) Critical Essays Ķ½¢ĶĪĪ reads, ŌĆ£Scholars of the present generation revere antiquity and demean the present.ŌĆØ õ╗ŖõĖ¢õ╣ŗÕŻ½ĶĆģ, Õ░ŖÕÅżÕŹæõ╗Ŗõ╣¤. Michael Puett, ŌĆ£Listening to Sages: Divination, Omens, and the Rhetoric of Antiquity in Wang ChongŌĆÖs LunhengŌĆ£, Oriens Extremus, vol. 45 (2005/06): 277.

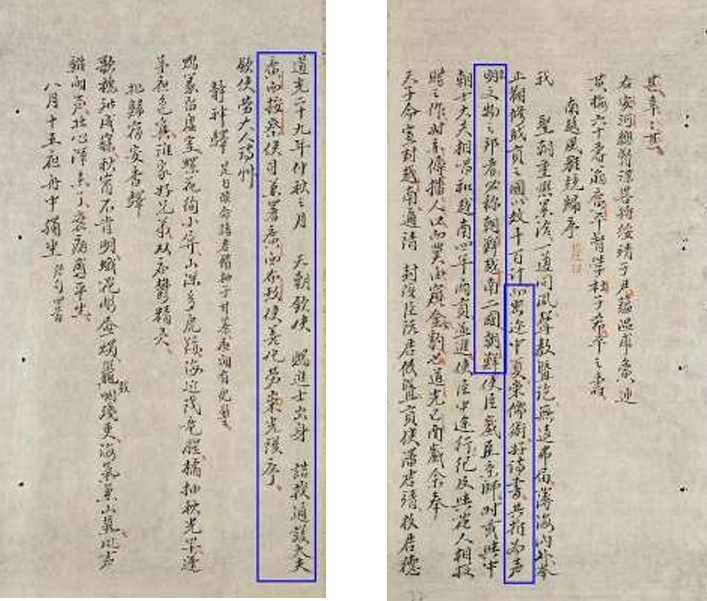

129) Mencius, ńøĪÕ┐āõĖŗ part II, 14, ŌĆ£Mencius said, 'The people are the most important element in a nation; the spirits of the land and grain are the next; the sovereign is the lightest. ÕŁ¤ÕŁÉµø░’╝ÜŌĆص░æńé║Ķ▓┤, ńżŠń©Ęµ¼Īõ╣ŗ, ÕÉøńé║Ķ╝Ģ.ŌĆØ Mencius, The Work of Mencius, translated by James Legge (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1960): p.483

130) Libing/lß╗Żi bß╗ćnh Õł®ńŚģ is a term found in the title of Gu YanwuŌĆÖs ķĪ¦ńéĵŁ” (1613-1682) famous voluminous work On Benefits and Faults of the EmpireŌĆÖs Local Administration Õż®õĖŗķāĪÕ£ŗÕł®ńŚģµøĖ; see https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&res=478756. It was praised as Politico-Geographical Studies µö┐µ▓╗Õ£░ńÉåÕŁĖ in Liang QichaoŌĆÖs ChinaŌĆÖs History of Scholarship during the Last Three Hundred Years õĖŁÕ£ŗĶ┐æõĖēńÖŠÕ╣┤ÕŁĖĶĪōÕÅ▓ (Shanghai: Zhonghua shuju, 1926)

131) The phrase the mechanism of the evolution of civilization µ¢ćµśÄķĆ▓Õī¢õ╣ŗµ®¤ is also found in Liang QichaoŌĆÖs essay ŌĆ£Shizhong dexing xiangfan chengyiŌĆØ (op. cit.), when Liang pointed out the hesitating attitude of scholar-officials toward the new could turn to be a great obstruction, dazhi Õż¦ń¬Æ, for the mechanism of the evolution of civilization.

132) In the early twentieth century, such a group of script-inventors had become a common and popular knowledge widely accepted within China, as exemplified in a solicitation of portraits of the four script-inventing sages Cang Jie, Ju Song, Qulu, and Zhu Xiang printed in the front page of Xinwen bao (ÕŠĄµ▒éÕĆēķĀĪ┬ʵ▓«Ķ¬”┬ĘõĮēńø¦┬ʵ£▒ĶźäÕøøĶü¢ķü║ÕāÅ, March 10, 1916). Regarding the three inventors mentioned in the VMTHS, both Cang Jie and Ju Song are the mythical chronicler and the historian, respectively, of the ancestor of the Chinese ŌĆō the Yellow Emperor; whereas Qu Lu stands out as an interesting case. In his Buddhist encyclopedia called Forest of Gems in the Garden of the Dharma µ│ĢĶŗæńÅĀµ×Ś (compiled in 668), Tang Buddhist monk Daoshi ķüōõĖ¢ ŌĆ£personified the names Brahm─ü and Kharosth─½ as script inventors by analyzing them to and fraternally ranking them with Cang Jie.ŌĆØ According to Daoshi, ŌĆ£In the past, there were three persons who created the writings. The elder is named Fan µóĄ whose writings goes rightward. The second is named Qulu õĮēńø¦ whose writing goes leftward. And the youngest is named Cang Jie whose writing goes downward. Fan and Qulu reside in India. The Yellow EmperorŌĆÖs historian Cang Jie lives in central China. Fan and Qu have taken scriptures from pure heaven.ŌĆØ µśöķĆĀµøĖõ╣ŗõĖ╗. ÕćĪµ£ēõĖēõ║║. ķĢĘÕÉŹµø░µóĄ. ÕģȵøĖÕÅ│ĶĪī. µ¼Īµø░õĮēńø¦. ÕģȵøĖÕĘ”ĶĪī. Õ░æĶĆģĶÆ╝ķĀĪ. ÕģȵøĖõĖŗĶĪī. µóĄõĮēńø¦Õ▒ģµ¢╝Õż®ń½║. ķ╗āÕÅ▓ĶÆ╝ķĀĪÕ£©µ¢╝õĖŁÕżÅ. µóĄõĮēÕÅ¢µ│Ģµ¢╝ÕćłÕż®. See Penglin Wang, Linguistic Mysteries of Ethnonyms in Inner Asia (MD: Lexington Books, 2018): 13-14. In ŌĆ£Discussions on Poetry from Yinbing HallŌĆØ ķŻ▓Õå░Õ«żĶ®®Ķ®▒, Liang Qichao also writes, ŌĆ£Efforts required to master QuluŌĆÖs script are greater than those spent for Cang JieŌĆÖsŌĆØ Ķ”üõ╣ŗõĮēńø¦ÕŁŚÕŖøÕż¦ķüÄÕĆēķĀĪ. Xinmin Congbao, vol. 9 (1902): 3.

133) Yinpan µ«Ęńøż (Chapters on the Yin King Pan Geng µ«ĘńÄŗńøżÕ║Ü) and Zhougao Õæ©Ķ¬ź (Zhou DynastyŌĆÖs twelve Imperial Mandates) are writings from Shangshu Õ░ܵøĖ (Book of Documents). In 1898, Qiu Tingliang ĶŻśÕ╗ʵóü (1857-1943), a well-known scholar from Wuxi ńäĪķī½ published an article on China Vernacular Journal õĖŁÕ£ŗÕ«śķ¤│ńÖĮĶ®▒ÕĀ▒ that helped the journal gain fame. QiuŌĆÖs article is titled ŌĆ£On Baihua Being the Root of ReformsŌĆØ Ķ½¢ńÖĮĶ®▒ńé║ńČŁµ¢░õ╣ŗµ£¼. Some scholar believes that QiŌĆÖs use of the term baihua ńÖĮĶ®▒ is significant, as he ŌĆ£popularized the new name for vernacular style hitherto mostly known as suhua õ┐ŚĶ®▒ (vulgar speech), using the euphemism baihua ńÖĮĶ®▒ (clear speech) instead.ŌĆØ Elisabeth Kaske, The Politics of Language in Chinese Education 1895ŌĆō1919 (Boston: Brill, 2008): 106. Noteworthy is his claim that, ŌĆ£Normally, sages proficient in manufacturing must compose books; when composing their books, they must employ clear speech (ŌĆ”) LetŌĆÖs prove it again: during the time of the Three Kings of the Xia ÕżÅ, Shang ÕĢå, and Zhou Õæ© dynasties, there were dictions when taking vows before their troops, announcements when moving the capital, for every single extraordinary move without minding declaring it out loud, and the intention was only their fear of their voices not loud enough to be heard by all under heaven. Hence, proclamations were all in clear speeches/vernacular language, but people of later generations found them difficult to comprehend, or inexplicable. Written ages long ago, the script remained intact, but the language changed. (ŌĆ”) HavenŌĆÖt you heard that people who recite Shijing Ķ®®ńČō, Chunqiu µśźń¦ŗ, Lunyu ’źüĶ¬×, Xiaojing ÕŁØńČō all intermittently use dialectsŌĆØ ÕćĪń▓ŠķĆÜĶŻĮķĆĀõ╣ŗĶü¢õ║║Õ┐ģĶæŚµøĖ┬ĘĶæŚµøĖÕ┐ģńÖĮĶ®▒ (ŌĆ”) ÕåŹĶŁēõ╣ŗõĖēńÄŗµÖéĶ¬ōÕĖ½µ£ēĶŠŁ┬ĘķüĘķāĮµ£ēĶ¬ź┬ʵ£ØÕ╗ĘõĖĆõ║īķØ×ÕĖĖĶłēÕŗĢõĖŹµåÜÕÅŹĶ”åµ╝öĶ¬¬Õż¦Ķü▓ń¢ŠÕæ╝. ÕĮ╝Õģȵäŵā¤µüÉõĖŹÕż¦µ¢╝Õż®õĖŗ. µĢģµ¢ćÕæŖńÜåńÖĮĶ®▒ĶĆīÕŠīõ║║õ╗źńé║õĮČÕ▒łķøŻĶ¦ŻĶĆģ. Õ╣┤õ╗ŻńĘ£ķéł┬ʵ¢ćÕŁŚõĖŹĶ«ŖĶĆīĶ¬×Ķ«Ŗõ╣¤ (ŌĆ”) õĖŹĶü×õ║║õ║║Ķ¬”ń┐ÆĶ®®┬ʵśźń¦ŗ┬ĘĶ½¢Ķ¬×┬ĘÕŁØńČōńÜåķø£ńö©µ¢╣Ķ©Ć. Zhongguo guanyin baihua bao, no. 20 (1898): 1b. QiuŌĆÖs essay was reprinted in contemporary newspapers, such as BeijingŌĆÖs Newspaper Collective Report ÕīŚõ║¼µ¢░Ķü×ÕĮÖÕĀ▒, 8th month (1901): 2785-2799; according to Deng Wei ķä¦Õüē, the essay was also republished in Wuxi baihua bao ńäĪķī½ńÖĮĶ®▒ÕĀ▒, even reprinted by Liang Qichao in Qingyi bao, and became a piece of Classic Literature of the Vernacular Movement ńÖĮĶ»Øµ¢ćĶ┐ÉÕŖ©ńÜäń╗ÅÕģĖµ¢ćńī«, in the Late Qing period. See Deng Wei, ŌĆ£On the Cultural Logic of the Vernacular Movement in the Late Qing Dynasty ŌĆō With a Focus on Qiu TingliangŌĆÖs ŌĆśOn Baihua Being the Root of ReformsŌĆÖŌĆØ Ķ®”Ķ½¢µÖܵĖģńÖĮĶ®▒µ¢ćķüŗÕŗĢńÜäµ¢ćÕī¢ķéÅĶ╝»ŌĆöõ╗źĶŻśÕ╗ʵóüĶ½¢ńÖĮĶ®▒ńé║ńČŁµ¢░õ╣ŗµ£¼ńé║õĖŁÕ┐ā, Dongyua luncong µØ▒ÕČĮĶ½¢ÕÅó, vol. 30, no. 3 (2009): 79.

134) Originally a term specifically describing one of the six principles of forming Chinese characters ÕģŁµøĖ, xiesheng/h├Āi thanh Ķ½¦Ķü▓ used to be defined by Western scholarship as characters ŌĆ£joined to a sound (Sono adjunctos in orig.), of which one half is merely phonetic and is used simply to indicate the name of the things which are signified by the other halfŌĆØ Tai TŌĆÖung, The Six Scripts or the Principles of Chinese Writing, translated by L. C. Hopkins (London: Cambridge University Press, 1954): 8. Modern linguists have treated this principle as the use of ŌĆ£the phonetic componentsŌĆØ of Chinese characters ŌĆ£to be grouped into phonetic Ķ½¦Ķü▓ series. A phonetic series consists of one basic character together with any other characters that employ that basic character as a phonetic component.ŌĆØ C.T. James Huang, Y.H. Audrey Li, Andrew Simpson, The Handbook of Chinese Linguistics (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2014): 585. During the Late Qing period, this term was quite freely used for phonetic combinations of other languages, such as in the section ŌĆ£Script studiesŌĆØ Ķć¬ÕŁĖ in Comprehensive Compilation of Writings on the Statecraft from the Royal Dynasty ńÜćµ£ØńČōõĖ¢µ¢ćńĄ▒ńĘ© (1901).

135) In his Riben shumuzhi µŚźµ£¼µøĖńø«Õ┐Ś (Catalogue of Japanese Books, Shanghai: Datong yishuju, 1897), Kang Youwei Õ║ʵ£ēńé║ (1858-1927) describes JapanŌĆÖs writing system as follows, ŌĆ£ŌĆ£Japanese script looks like ours but slightly mixed with K┼½kaiŌĆÖs ń®║µĄĘthirteen-iroha script µŚźµ£¼µ¢ćÕŁŚńīČÕÉŠµ¢ćÕŁŚõ╣¤õĮåń©Źķø£ń®║µĄĘõ╣ŗõ╝ŖÕæéµ│óÕŹüõ╣ŗõĖēĶĆ│.ŌĆØ K┼½kai (also known posthumously as K┼Źb┼Ź-Daishi Õ╝śµ│ĢÕż¦ÕĖ½, 774ŌĆō835) was the founder of the Esoteric Shingon ń£¤Ķ©Ć (mantra) school of Buddhism in Japan. According to Ry┼½ichi Abe, ŌĆ£K┼½kai was also said to have invented kana, the Japanese phonetic orthography, and the Iroha, the kana syllabary. In the Iroha table, the kana letters are arranged in such a manner as to form a waka that plainly expresses the Buddhist principle of emptiness.ŌĆØ Ry┼½ichi Abe, The Weaving of Mantra ŌĆō K┼½kai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999): p.3. It should be noted that the Meiji period also witnessed a number of script reform movements, among which there were various groups working toward the reforms of the iroha system: ŌĆ£The members of the Iroha Kai, inaugurated also in 1882 after two years of discussion, were mostly educators (ŌĆ”) Those involved in formal education were naturally more enthusiastic than others about spreading popular education, and the object of the Iroha Kai was to search for a way more efficiently achieving this objective. The Irohabun Kai was started in the same year by businessmen, journalists, and graduates of Kei┼Ź Gijuku µģȵćēńŠ®ÕĪŠ, a school founded by Fukuzawa Yukichi.ŌĆØ Navette Twine, ŌĆ£Toward Simplicity: Script Reform Movements in the Meiji Period ŌĆ£, Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 38, no. 2 (1983): p.121.

136) A note by F. Paillart in the Review of the History of French Colonies (1926) reads, ŌĆ£It was in 1624 that Father Alexandre de Rhodes (1593-1660), born in Avignon, but whom all contemporaries qualified as French, arrived in Cochinchina the fact has a certain importance, Father Alexandre de Rhodes being the real inventor of the quoc-ngu that some insist on attributing to the Portuguese.ŌĆØ (p. 303, note 1). However, the Indochina in the Past ŌĆō Exposition of Documents Relevant to the History of Indochina (Hanoi: Le Van Tan, 1938) emphasizes, ŌĆ£Father de Rhodes has the great merit of codifying and making more practical the transcription of Vietnamese language into Latin characters, which the Portuguese had adopted.ŌĆØ (no pagination). This viewpoint has now been widely accepted within Vietnam. The Britannica also writes, ŌĆ£De Rhodes perfected a romanized script, called Quoc-ngu, developed by the earlier missionaries Gaspar de Amaral and Antonio de Barbosa, and he added special marks to the roman letters, denoting tones, which in Vietnamese indicate the meaning of words.ŌĆØ https://www.britannica.com/biography/Alexandre-de-Rhodes

137) Kh├óm ─Éß╗ŗnh Viß╗ćt Sß╗Ł Th├┤ng Gi├Īm CŲ░ŲĪng Mß╗źc µ¼ĮÕ«ÜĶČŖÕÅ▓ķĆÜķææńČ▒ńø«by the Nguyß╗ģn DynastyŌĆÖs Academia Historica ķś«µ£ØÕ£ŗÕÅ▓ķż©, compiled during the reign of Emperor Tß╗▒ ─Éß╗®c ÕŚŻÕŠĘ (1847-1883), first printed in 1884.

138) ─Éß║Īi Nam Thß╗▒c Lß╗źc Õż¦ÕŹŚÕ»”ķīä is the Nguyß╗ģn DynastyŌĆÖs official and primary source, providing historical records in the imperial annal format, from the rise of the Nguyß╗ģn Lords until 1925.

139) Accompanying the ─Éß║Īi Nam Thß╗▒c Lß╗źc, ─Éß║Īi Nam Liß╗ćt Truyß╗ćn Õż¦ÕŹŚÕłŚÕé│ consists of two parts Qianbian/Tiß╗ün bi├¬n ÕēŹńĘ© (Prequel Biographies of the Nguyß╗ģn LordsŌĆÖ period) and Zhengbian/Ch├Łnh bi├¬n µŁŻńĘ© (Principal Biographies of the Nguyß╗ģn Dynasty).

140) Also compiled under the reign of Emperor Tß╗▒ ─Éß╗®c, ─Éß║Īi Nam Nhß║źt Thß╗æng Ch├Ł Õż¦ÕŹŚõĖĆńĄ▒Õ┐Ś is the Nguyß╗ģn DynastyŌĆÖs official geographical records of Vietnam.

141) Lß╗ŗch Triß╗üu Hiß║┐n ChŲ░ŲĪng Loß║Īi Ch├Ł µŁĘµ£Øµå▓ń½ĀķĪ×Õ┐Ś is an encyclopedic work compiled by Phan Huy Ch├║ µĮśĶ╝ص│©, 1782-1840) during a period of ten years (1809-1819).

142) V├ón ─É├Āi Loß║Īi Ngß╗» ĶĢōĶ¢╣ķĪ×Ķ¬× is also an encyclopedia by L├¬ Qu├Į ─É├┤n (ķ╗ÄĶ▓┤µāć, 1726ŌĆō1784), collecting essential knowledge of philosophy, literature, geography, or cosmology shared by Vietnamese literati up to the eighteenth century.

144) Kiß║┐n V─ān Tiß╗āu Lß╗źc Ķ”ŗĶü×Õ░Åķīä is another encyclopedic work by L├¬ Qu├Į ─É├┤n, selectively presenting historical, literary, geographical and ideological records from Vietnam through times until the eighteenth century.

145) Ho├Āng Viß╗ćt Nhß║źt Thß╗æng DŲ░ ─Éß╗ŗa Ch├Ł ńÜćĶČŖõĖĆńĄ▒Ķ╝┐Õ£░Õ┐Ś was compiled by L├¬ Quang ─Éß╗ŗnh ķ╗ÄÕģēÕ«Ü (1759-1813) in 1806, only four years after the foundation of the Nguyß╗ģn Dynasty by Emperor Gia Long ÕśēķÜå in 1802.

146) Gia ─Éß╗ŗnh Th├Ānh Th├┤ng Ch├Ł ÕśēÕ«ÜÕ¤ÄķĆÜÕ┐Ś was compiled during the 1820s (or 1830s) by Trß╗ŗnh Ho├Āi ─Éß╗®c ķ䣵ćĘÕŠĘ (1765-1825), describing various aspects of the Gia ─Éß╗ŗnh region (including the nowadays Mekong Delta), such as mountains and rivers, custom, local products, or citadels.

147) The printed version A.567 lists it as Nghß╗ć An Phong Thß╗Ģ Thoß║Īi õ╣éÕ«ēķó©Õ£¤Ķ®▒. However, the correct title should be Nghß╗ć An Phong Thß╗Ģ K├Į õ╣éÕ«ēķó©Õ£¤Ķ©ś, which is a work by B├╣i DŲ░ŲĪng Lß╗ŗch ĶŻ┤µźŖńōæ (1757-1828), recording geography, custom, sceneries, and outstanding figures of the province.

148) ─Éß╗ō B├Ān Th├Ānh K├Į ķŚŹµ¦āÕ¤ÄĶ©ś is a section from Nguyß╗ģn Thß╗ŗ T├óy SŲĪn K├Į ķś«µ░ÅĶź┐Õ▒▒Ķ©ś (Records on the Nguyß╗ģn Clan of T├óy SŲĪn) by Nguyß╗ģn V─ān Hiß╗ān ķś«µ¢ćķĪ». See ─Éß╗ō B├Ān Th├Ānh K├Į ķŚŹµ¦āÕ¤ÄĶ©ś, translated into modern Vietnamese by T├┤ Nam, Sß╗Ł ─Éß╗ŗa, no. 19-20 (1970): 232-248.

149) In Collection of One Hundred Vietnamese Texts, 2nd edition (Hanoi: F. H. Schneider, 1905), there is an account on ch├óu, ŌĆ£The word Ch├óu ÕĘ×, administrative division of Annam, only applies to mountainous territories and peoples in whole or in part of aborigines Thß╗Ģ, M├Īn, MŲ░ß╗Øng, X├Ī, M├©o, B├┤ng, X├Ī B├┤ng etc. A large number of Ch├óu are designated by a single word, unlike the Huyß╗ćn ńĖŻ whose name always includes two words. In Tonkin, we specifically call: 1. Thß║Łp-lß╗źc-ch├óu, that is to say the sixteen Ch├óu, sixteen of these districts, formerly belonging to the province of HŲ░ng Ho├Ī, and distributed today between the provinces of PhŲ░ŲĪng L├óm, HŲ░ng Ho├Ī, L├Żo Cay and SŲĪn La which counts the most.ŌĆØ (p. iv, note 10). Since there is no extant information about the work HŲ░ng Ho├Ī Thß║Łp Lß╗źc Ch├óu K├Į ĶłłÕī¢ÕŹüÕģŁµ┤▓Ķ©ś, it remains unclear about its author, date of composition, and contents. It should also be noted that the term Ch├óu in the title should have been written as ÕĘ× instead of µ┤▓.

150) Phß╗¦ Man Tß║Īp Lß╗źc µÆ½ĶĀ╗ķø£ķīä is a work compiled in 1871 by Nguyß╗ģn Tß║źn ķś«ńĖē reporting the Nguyß╗ģn DynastyŌĆÖs pacification of the ethnic minoritiesŌĆÖ rebellions in the West of Quß║Żng Ng├Żi province.

151) The Zuozhuan ÕĘ”Õé│ reports the case of a senior official by the name of Ji Tan ń▒ŹĶ½ć from the Jin µÖēstate in the Spring and Autumn period (770 BCEŌĆō476 BCE). In a diplomatic mission to the Zhou Õæ© state, Ji did not answer well the queries raised by the King of Zhou. The King satirically criticized him, saying that he ŌĆ£gave all the historical accounts except those about his own ancestorsŌĆØ µĢĖÕģĖÕ┐śńź¢. This set-phrase (alternatively written as ŌĆ£Ji Tan wangzuŌĆØ ń▒ŹĶ½ćÕ┐śńź¢) has been used as a criticism against those who forget their past, or their origins.

152) The phrase is believed to come from Zuozhuan. However, following Liu ShangciŌĆÖs ÕŖēÕ░ܵģł Chunqiu Gongyang zhuan yizhu µśźń¦ŗÕģ¼ńŠŖÕé│ĶŁ»µ│© (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2010, vol. 1): p1, Thomas J├╝lch concludes that, ŌĆ£In fact this passage does not appear in the Zuozhuan but in the Gongyang zhuan Õģ¼ńŠŖÕé│, chapter ŌĆśYingong ķÜ▒Õģ¼ŌĆÖŌĆØ see Thomas J├╝lch, ZhipanŌĆÖs Account of the History of Buddhism in China, vol. 1 ŌĆ£Fozu tongjiŌĆØ (Boston: Brill, 2019): p.99, note 272; see also Wang Zichu ńÄŗÕŁÉÕłØ, ŌĆ£Significance of Zhang Yining' Critic on Zhou CalendarŌĆØ Õ╝Ąõ╗źÕ»¦Õ░ŹÕ橵ŁŻÕĢÅķĪīńÜäńĖĮńĄÉÕÅŖÕ£░õĮŹ, Lantai shijie ĶśŁÕÅ░õĖ¢ńĢī, no. 4 (2019): 140-144.

153) Ma Yuan led the Chinese troops invading Jiaozhi during the period of 42-43 AD. The biography of Ma Yuan ķ”¼µÅ┤ÕłŚÕé│ recorded in the vol.24 of the Annals of the Later Han dynasty ÕŠīµ╝óµøĖ requoted a citation from Records of Guangzhou Õ╗ŻÕĘ×Ķ©ś by Li Xian µØÄĶ│ó of the Tang dynasty, saying that, ŌĆ£Ma Yuan arrived in Jiaozhi (i.e., Northern part of Vietnam nowadays), erected bronze pillars to mark the far-end borders of the Han dynasty.ŌĆØ µÅ┤Õł░õ║żķś», ń½ŗķŖģµ¤▒, ńé║µ╝óõ╣ŗµźĄńĢīõ╣¤.

154) All of those accounts are recorded in the Kh├óm ─Éß╗ŗnh Viß╗ćt Sß╗Ł Th├┤ng Gi├Īm CŲ░ŲĪng Mß╗źc. See Quß╗æc sß╗Ł qu├Īn Triß╗üu Nguyß╗ģn, The Imperial Approved Outline of the General Reflections of the History of Viß╗ćt, translated from literary Chinese into modern Vietnamese by Viß╗ćn Sß╗Ł Hß╗Źc (Hanoi: Gi├Īo Dß╗źc, 2007): pp.110-111.

155) Xiaoxue zuanzhu Õ░ÅÕŁĖń║éĶ©╗ is originally composed by Zhu Xi µ£▒ńå╣ and annotated by Gao Yu ķ½śµäł of the Qing dynasty; see https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=en&res=995100. As a model scholar-official of the Qing dynasty, Chen Hongmou ķÖ│Õ«ÅĶ¼Ć (1696-1771) mandated it to be included in the ŌĆ£daunting collectionŌĆØ of texts for the charitable schools he founded in Yunnan. See Cynthia J. Brokaw, Commerce in Culture ŌĆō The Sibao Book Trade in the Qing and Republican Periods (Cambridge (MA) and London: Harvard University Press, 2007): p.405, note 118.

156) ZuofeiŌĆÖan rizuan µś©ķØ×ĶōŁµŚźń║é is a work by Zheng Xuan ķäŁĶÉ▒ (ca. 1602-1646) of the Late Ming dynasty, whose contents can be classified into three main topics as regimen ķżŖńö¤, official admonition Õ«śń«┤, and virtuous persuasion ÕŗĖÕ¢ä. It became a compilation model during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties; it was also introduced to and circulated in Japan and Korea. See Chieh-Min Chou Õæ©Õ®ĢµĢÅ, ŌĆ£The Study of Zuofeian rizuan by Zheng Xuan in Late Ming dynastyŌĆØ µÖܵśÄķäŁĶÉ▒µś©ķØ×ĶōŁµŚźń║éńĀöń®Č, MasterŌĆÖs Degree dissertation, Taiwan Chenggong University, Liberal Arts College, Department of Literature, 2014.

157) This may be another name for Wu dazhou tushuo õ║öÕż¦µ┤▓Õ£¢Ķ¬¬ by Giulio Alenio, edited by Qian Xizuo ķīóńåÖńźÜ, published by Shanghai shuju õĖŖµĄĘµøĖÕ▒Ć (1898).

158) This may be a shorter title of Gujin wanguo gangjian ÕÅżõ╗ŖĶɼգŗńČ▒ķææ (Singapore: Jianxia shuyuan, 1838); see https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=151372&remap=gb. Although the extant publication has no authorŌĆÖs name printed, it has been attributed to Karl Friedrich G├╝tzlaff (1803-1851); see Guo Xiuwen ķāŁń¦Ćµ¢ć, ŌĆ£Dongxiyang kao meiyue tongjizhuan de zhongjiao chuanbo celueŌĆØ µØ▒Ķź┐µ┤ŗĶĆāµ»Åµ£łńĄ▒Ķ©śÕé│ńÜäÕ«ŚµĢÖÕé│µÆŁńŁ¢ńĢź, Xueshu yanjiu ÕŁĖĶĪōńĀöń®Č, no. 8 (2016): 114. However, there is another book with a quite similar title, Guojin wanguo gangjianlu ÕÅżõ╗ŖĶɼգŗńČ▒ķææķīä by Robert Morrison (1782-1834), as seen in a version of it printed in Japan: Moreish├┤ µ©Īń”«Õ┤¦. Kokon bankoku k┼Źkanroku ÕÅżõ╗ŖĶɼգŗńČ▒ķæÆķīä, with Japanese guiding marks Ķ©ōńé╣ by ┼ītsuki Seishi Õż¦µ¦╗Ķ¬Āõ╣ŗ, corrected by Yanagisawa Shindai µ¤│µŠżõ┐ĪÕż¦ (Tokyo: T┼Źsei Kamejir┼Ź, 1874). Confused by the resemblance of the two titles, some modern scholars consequently identify Gujin wanguo gangjian as MorrisonŌĆÖs work, as in the case of Chou Yu-wen Õ橵äܵ¢ć, ŌĆ£The Introduction of American Education by Missionaries and Chinese Officials and Commoners in Late ChŌĆÖing China before 1894 µÖܵĖģńö▓ÕŹłÕēŹÕ£©ĶÅ»õĖŁÕż¢õ║║ÕŻ½Õ░Źµ¢╝ńŠÄÕ£ŗµĢÖĶé▓ńÜäõ╗ŗń┤╣, Jiaoyu yanjiu jikan µĢÖĶé▓ńĀöń®ČķøåÕłŖ/ Bulletin of Educational Research, vol. 65, no.1 (2019): 121.

159) It is possibly Wanguo jinzheng kaolue ĶɼգŗĶ┐æµö┐ĶĆāńĢź by Zou Tao ķäÆÕ╝ó (Shanghai: Sanjielu, 1901).

160) This may be a shorter title of Xixue kaolue Ķź┐ÕŁĖĶĆāńĢź by Ding Weiliang õĖüķ¤ÖĶē» (Tongwenguan, 1883).

161) Hß╗Źc cß╗®u ti├¬n sinh ÕŁĖń®ČÕģłńö¤ is a term close to English word ŌĆ£pedant, ŌĆ£ referring to a person who ŌĆ£A person who excessively reveres or parades academic learning or technical knowledge, often without discrimination or practical judgement. Hence also: one who is excessively concerned with accuracy over trifling details of knowledge, or who insists on strict adherence to formal rules or literal meaning.ŌĆØ (Oxford English Dictionary).

162) Often ranked as the second revolutionary newspaper (only after Sun ZhongshanŌĆÖs ÕŁ½õĖŁÕ▒▒ Zhongguo ribao õĖŁÕ£ŗµŚźÕĀ▒), Shijie gongyibao õĖ¢ńĢīÕģ¼ńøŖÕĀ▒ is a Hong Kong publication inaugurated in November 1903, by Lin Hu µ×ŚĶŁĘ and Tan Sanmin ĶŁÜõĖēµ░æ as founders and Zheng Guangong ķäŁĶ▓½Õģ¼ (1880-1906) as editor-in-chief. Its supplement Yijuebao õĖĆÕÖ▒ÕĀ▒ employed humorous and satirical language to criticize contemporary politics; see Li Jiayuan µØÄÕ«ČÕ£Æ, Xianggang baoye zatan ķ”ÖµĖ»ÕĀ▒µźŁķø£Ķ½ć (Hong Kong: Sanlian shudian, 1989): p.53; Chen Ming ķÖ│ķ│┤, A History of the Press in Hong Kong 1841-1911 ķ”ÖµĖ»ÕĀ▒µźŁÕÅ▓ń©┐ (Hong Kong: Huaguang baoye youxian gongsi, 2005): pp.127-128.

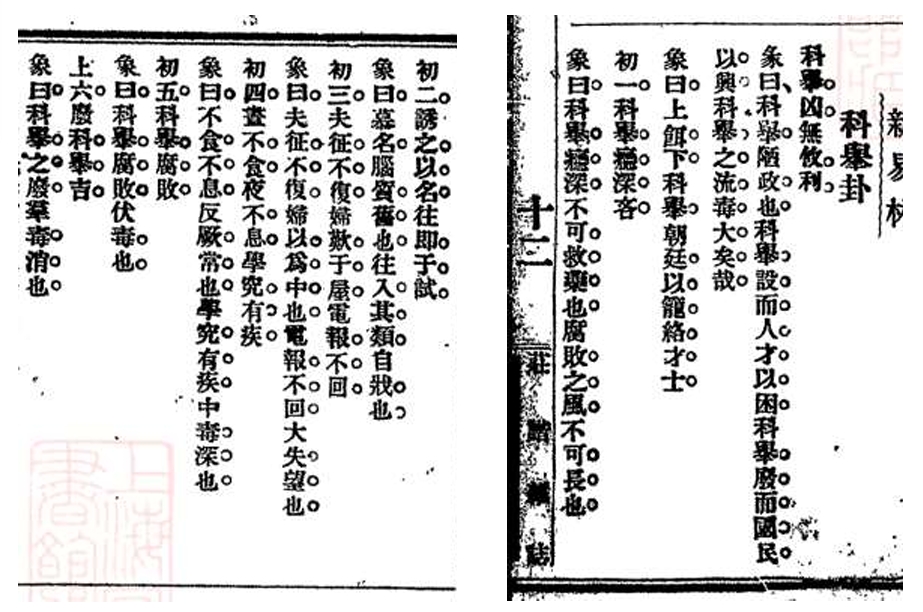

In 1904, Zheng Guangong selected humorous writings and traditional Chinese telling and singing pieces of art printed in newspapers and periodicals, and published them together in a magazine called New Collection of Contemporary Laughing Matters µÖéĶ½¦µ¢░ķøå. One of its main categories is called ŌĆ£WenjieŌĆØ µ¢ćńĢī (Literary World) divided into a number of sections, of which is the ŌĆ£Hexagram of the Civil Service Examination.ŌĆØ See Li Wanwei µØÄÕ®ēĶ¢ć, ŌĆ£Qingmo Minchu YueGang gemingpai baokanŌĆØ µĖģµ£½µ░æÕłØń▓ĄµĖ»ķØ®ÕæĮµ┤ŠÕĀ▒ÕłŖŌĆØ, Wenshi zhishi, no. 12 (2012): 31-32.

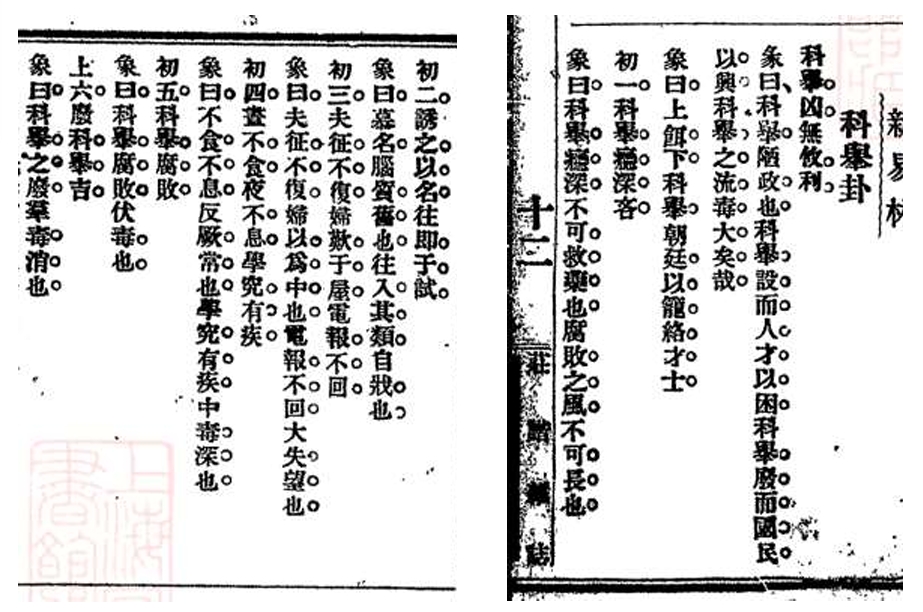

Based on the six-line structure of a hexagram ÕŹ” in the Classic of Changes µśōńČō, accompanied by judgment ÕĮ¢/hexagram statements ÕŹ”ĶŠŁ, and line statements ńł╗ĶŠŁ, the ŌĆ£Hexagram of Civil Service ExaminationŌĆØ allows writers to express their critiques against the examination system in fourteen short paragraphs. This established format and topic became inspiring and was practiced by a number of literati. An extant example called ŌĆ£Hexagram of the Abolition of the Civil Service ExaminationŌĆØ Õ╗óń¦æĶłēÕŹ” can be found in the supplement Xiaoxian lu µČłķ¢Æķīä (no. 593, September 27, 1905, ShanghaiŌĆÖs Tongwen Hubao ÕÉīµ¢ćµ╗¼ÕĀ▒). Judged by the quoted phrases, the ŌĆ£Hexagram of the Civil Service ExaminationŌĆØ mentioned here seems to be reprinted in the supplement Zhuangxie zazhi ĶÄŖĶ½¦ķø£Ķ¬ī, in a section called ŌĆ£Xin Yilin µ¢░µśōµ×ŚŌĆØ (vol. 2, no. 1-10, 1909).

163) In his Liaozhai Zhiyi ĶüŖķĮŗĶ¬īńĢ░, Pu Songling ĶÆ▓µØŠķĮĪ(1640-1715) points out seven similarities with which a candidate may be identified in his commentaries on the tale of ŌĆ£Wang ZiŌĆÖanŌĆØ ńÄŗÕŁÉŌĆØ. When entering the examination hall, a county candidate finds his seven similarities there: (1) Being barefooted and carrying a basket, he looks like a beggar; (2) Being called and shouted by the examination official, he looks like a prisoner; (3) Finding himself in the isolated examination cell, he looks like a bee chilled by the last days of autumn; (4) Getting out of the examination hall, he looks like a sick bird released from its cage; (5) Dreaming of a success and imagining of a failure, he cannot relax and looks like a tied up monkey; (6) Hearing othersŌĆÖ success, he feels so depressed and looks like a poisoned fly; and (7) Having learned the result of the exam, he looks like a dove whose egg has been broken is now preparing to rebuild a new nest and to hatch a new egg.

164) Although both the extant woodblock-printed and hand-written copies of VMTHS have the same character vi/wei Õ£Ź, it might have been an alternative of ķŚł (doors of the palace). This character is specifically used in a number of terms relevant to the civil service examination, such as ruwei ÕģźķŚł (ŌĆ£to enter the examination-hall, as the examiners for the 2nd and 3rd degreesŌĆØ), chuwei Õć║ķŚł (ŌĆ£to leave the examination-hall, as the examiners, after issuing the list of successful candidatesŌĆØ), chunwei µśźķŚł (ŌĆ£the spring examination, for the 3rd degree, held triennially at PekingŌĆØ), or qiuwei ń¦ŗķŚł (ŌĆ£the autumn examination, for the 2nd degree, held triennially in every provincial capitalŌĆØ); see GilesŌĆÖ English-Chinese Dictionary, p.1556. Noteworthy is that Giles also records weixing ķŚłÕ¦ō as ŌĆ£examination names, a form of lottery on the names of successful competitors.ŌĆØ This is, in fact, weixing ķŚłÕ¦ō (ŌĆ£the popular betting pool based on the surnames of top scorers in the local and national examinations in ChinaŌĆØ); see Koos Kuiper, The Early Dutch Sinologists (1854-1900): Training in Holland and China, Functions in the Netherlands Indies vol.2 (Boston: Brill, 2017): p.856, note 5. existed for a few decades and ended with the abolition of the civil service examination in China in 1905, ŌĆ£In 1860, weixing was formally introduced in Guangdong as a means of raising public revenues. It was banned in Guangdong in 1876 (ŌĆ”). Thus, gambling operators fled to Macao and Hong Kong and set up operations there. In 1867, gambling was made legal in Hong Kong (ŌĆ”). Faced with such direct and severe competition, the gambling business in Macao was hit very hard. Some gambling operators even moved their businesses from Macao to Hong Kong in search of better returns.ŌĆØ; see Victor Zheng, Po-san Wan, Gambling Dynamism: The Macao Miracle (London: Springer, 2013): p.41. In weixing, candidatesŌĆÖ family names were sold as lottery tickets, and like any other gambling games, cheatings also occurred. Gamblers aimed at candidates whose family names appeared rare or unpopular, and hired professionals to take the examination for them to ensure their success. Although producing great revenues for the government (it was reported that Guangdong Governor Zhang Zhidong Õ╝Ąõ╣ŗµ┤× (1837-1909) enjoyed a revenue of more than 5,000,000 taels of silver from weixing), this consequently gambled and corrupted the examination system; see An Guanglu Õ«ēÕ╗Żńź┐, ŌĆ£Civil Service Examination and GamblingŌĆØ ń¦æĶłēĶĆāĶ®”ĶłćĶ│ŁÕŹÜŌĆØ, Wenshi tiandi, no. 9 (2010): 74; Yu Yongpin õ┐×ÕŗćÕ¼¬, A Brief Investigation on Weixing during the Late Qing Dynasty µĖģµ£½Õ╗ŻµØ▒ŃĆīķŚłÕ¦ōŃĆŹĶĆāńĢź, Lingnan luntan, no. 1 (1995): 15-20. Contemporary newspapers, such as Zilin Hubao ÕŁŚµ×Śµ╗¼ÕĀ▒, or Xinwen Bao µ¢░Ķü×ÕĀ▒, had several articles on this socio-political phenomenon, among which the long essay titled ŌĆ£On Guangdong Governor's Recruitment of Weixing MerchantsŌĆØ Ķ½¢ń▓ĄńØŻµŗøÕģģķŚłÕ¦ōÕĢåõ║║õ║ŗ (Xinwen bao, March 3, 1896) is noteworthy. Vietnamese literati might have learned about weixing through those Chinese newspapers, although it did not happen in their country.

165) Rui Wang, The Chinese Imperial Examination System: An Annotated Bibliography (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2013): p.154.

166) There is a mistake with the date here, as the gengzi year (1900) was not the time for the abolition of the eight-legged essay in Chinese civil examination. On January 19, 1900, the Qing Court announced that, ŌĆ£by imperial decree, in honor of the emperorŌĆÖs thirtieth birthday in 1901ŌĆ”there are to be special examinations at the provincial level in the gengzi year of 1900, and at the metropolitan level in the xinchou year of 1901.ŌĆØ Douglas R. Reynolds, China, 1895-1912 State-Sponsored Reforms and China's Late-Qing Revolution: Selected Essays from Modern Chinese History, 1840-1919 (Armonk: Taylor & Francis Group, 1995): p.87. Unfortunately, due to the Boxer Rebellion, the planned special examinations did not take place. On August 29, 1901, an imperial edict was issued, officially abolishing the eight-legged essay in the civil examinations, ŌĆ£all examination essays whether political discourses or extrapolation of the Confucian Classics had to be written in unbound non-metrical prose.ŌĆØ Elisabeth Kaske, The Politics of Language in Chinese Education, op. cit., 254. The abolition was a critical decision made after several memorials sent to the throne by Zhang Zhidong, Zhang Yuanji Õ╝ĄÕģāµ┐¤ (1867-1959) and Kang Youwei (ibid., p. 85), ŌĆ£signaling that examination questions for the shengyuan degree would now include Western learning as well as Chinese learning. Moreover, it became clear that at the higher examination levels at least one set of policy questions would focus on ŌĆśworld politics.ŌĆÖŌĆØ Richard J. Smith, The Qing Dynasty and Traditional Chinese Culture (Lanham; Boulder; New York; London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015): p.393.

167) Founded in Beijing in October 1895, this society lasted for only five months because of the Qing DynastyŌĆÖs ban on the establishment of private societies. However, it had tremendous socio-political impacts on Chinese society as it was spreading out from the capital to provinces; see Rebecca E. Karl, Peter Zarrow, eds. Rethinking the 1898 Reform Period: Political and Cultural Change in Late Qing China (Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press, 2002): p.142.

168) Both the prefaces for the Society in Beijing and Shanghai by Kang Youwei and Zhang Zhidong respectively do not contain the cited sentence; see ŌĆ£Jingshi Qiangxuehui xuŌĆØ õ║¼ÕĖ½Õ╝ĘÕŁĖµ£āÕ║Å, Qiangxuebao, no. 1 (1895); ŌĆ£Shanghai Qiangxuehui xuŌĆØ õĖŖµĄĘÕ╝ĘÕŁĖµ£āÕ║Å, Xinwenbao, December 4, 1895). However, a similar sentence is found in Liang QichaoŌĆÖs letter addressed to Chen Baozhen ķÖ│Õ»Čń«┤ (1831-1900), titled ŌĆ£On What Hunan Should DoŌĆØ Ķ½¢µ╣¢ÕŹŚµćēĶŠ”õ╣ŗõ║ŗ. LiangŌĆÖs sentence reads, ŌĆ£Thus, if we now want to enlighten the peopleŌĆÖs mind, we need to enlighten the gentryŌĆÖs mind; and as we should pass it on to the mandarin force whom we still do not know all, we therefore must enlighten the mandarinŌĆÖs mind, making it the starting point of everything.ŌĆØ ÕŹ│õ╗ŖµŚźµ¼▓ķ¢ŗµ░æµÖ║, ķ¢ŗń┤│ µÖ║, ĶĆīÕüćµēŗµ¢╝Õ«śÕŖøĶĆģ, Õ░ÜõĖŹń¤źÕćĪÕ╣Šõ╣¤, µĢģķ¢ŗÕ«śµÖ║, ÕÅłńé║Ķɼõ║ŗõ╣ŗĶĄĘķ╗×.

169) In the reign of King Gia Long of the Nguyß╗ģn Dynasty, the Imperial Academy was founded in Huß║┐ in 1803 under the name of ─Éß╗æc Hß╗Źc ─ÉŲ░ß╗Øng ńØŻÕŁĖÕĀé. It was renamed Quß╗æc Tß╗Ł Gi├Īm Õ£ŗÕŁÉńøŻ in March 1820 under the reign of King Minh Mß║Īng. An article by Robert de La Susse, titled ŌĆ£Education in AnnamŌĆØ printed in Les Annales Coloniales (June 03, 1913), also shows that French education had been introduced in this imperial institution around the time of its publication, ŌĆ£In addition, there is a special third-grade school in Hue called College Quß╗æc Tß╗Ł Gi├Īm. Quß╗æc Tß╗Ł Gi├Īm is the Vietnamese Prytan├®e; it receives the sons of royal or princely families and the children of the mandarins. There also modernism begins to do its work, and in the pagoda where the young Vietnamese used to learn exclusively the Chinese characters, the word of a French master comes today to be heard. The fact that French lessons are not the least assiduously attended is the best proof of the success of our teaching.ŌĆØ (p. 2).

170) Zheng Guanying ķäŁĶ¦Ćµćē in the chapter ŌĆ£Civil Examination, Part 1 ĶĆāĶ®”õĖŖŌĆØ of his book Warning Words to a Prosperous Word ńøøõĖ¢ÕŹ▒Ķ©Ć writes that, ŌĆ£Although they are heroic learned people who must have their unity of heart-and-strength, they are worn out by the useless literature for the civil examination.ŌĆØ ķø¢Ķ▒¬Õéæõ╣ŗÕŻ½, õ║”õĖŹÕŠŚõĖŹõ╗źµ£ēńö©õ╣ŗÕ┐āÕŖø, µČłńŻ©µ¢╝ńäĪńö©õ╣ŗµÖéµ¢ć.

171) ŌĆ£College Quß╗æc Hß╗ŹcŌĆØ or ŌĆ£Quß╗æc Hß╗Źc High SchoolŌĆØ (The School for National Studies) was established by the French Governor GeneralŌĆÖs ordinance issued on November 18, 1896. The teaching at the school was covered by five French professors with the assistance of three native teachers particularly chosen; see Les Annales Coloniales, June 03, 1913, p. 2.