Abstract

Kaifūsō 懷風藻 from the Nara period is the oldest surviving collection of Japanese kanshi 漢詩. Its poems were in a formative stage, imitating the poetry of the Six Dynasties and early Tang periods. However, after the middle and later Heian period, distinctly Japanese forms of kanshi such as the seven-character regulated verse and kudaishi 句題詩 began to emerge amidst the popularity of Bai Juyi’s poetry. During the Kamakura period, the practitioners of kanshi starkly shifted from aristocrats to Zen monks, marking the beginning of what is called gozan bungaku 五山文學, which continued into the Muromachi period. During this time, the literature of the Song and Yuan dynasties—especially Su Shi and Huang Tingjian’s poetry from the Northern Song—was held in high regard, as well as the poetry of Du Fu, who greatly influenced them. Influenced by these three figures, Zen monks of the Muromachi period not only composed kanshi, but also gave lectures on their poetry and preserved their teachings in shōmono. These shōmono hold unique significance in the history of Japanese kanshi studies as the first interpretive works. This paper outlines the reception of Du Fu’s poetry up until the early era of Gozan Bungaku and then introduces four shōmono on Du Fu’s poetry from the middle period and beyond.

-

Keywords: medieval Japan, Zen monks, Du Fu’s poetry, shōmono, Shinge Gentei, Shinge okudan, Kōsei Ryūha, Toshi Zokusuishō, Jinro Seiju, Zokuokudan, Setsurei Eikin, Toshi shō

Introduction

The oldest surviving collection of kanshi ʺ¢Ë©© (Japanese poetry written with Chinese characters) in Japan is called Kaif≈´s≈ç Êá∑È¢®Ëóª. It has a preface dated to the third year of the Tenpy≈ç sh≈çh≈ç §©Âπ≥ÂãùÂØ∂ era (751), and it can be said that kanshi in Japan first took shape in this collection. Kaif≈´s≈ç is a collection of poems from the time of the ≈åmi court ËøëʱüÊúù of Emperor Tenji (r. 661‚Äì671) to the first half of the Nara period (710‚Äì784), with everything compiled in one volume. Poets of the Kaif≈´s≈ç were at the stage of composing works that learned from and were modeled after those of the Six Dynasties and Early Tang. During a time when Japan was trying to establish a ritsury≈ç Âæ㉪§ legal system modeled after the Tang dynasty, the composition of kanshi served as a means to demonstrate that Japan‚Äôs literature was not inferior to the literature of other countries within the East Asian Sinographic cultural sphere. The poems in Kaif≈´s≈ç were composed by following the examples of Qi and Liang poetry from works such as Wenxuan ÊñáÈÅ∏, Yutai xinyong ÁéâËá∫Êñ∞Ë©Ý, and Yiwen leiju ËóùÊñáÈ°ûËÅö. Additionally, as for the case of early Tang poetry, works were mainly created by imitating the works of poets like Wang Bo ÁéãÂãÉ (649-676) and Luo Binwang Èß±Ë≥ìÁéã (640-684). However, at this point, kanshi had not yet developed a distinct Japanese style.

Next, in the early Heian period during the reign of Emperor Saga 嵯峨 in the Kōnin弘仁 era (809–823), three imperial

kanshi collections were compiled:

Ryōunshū 凌雲集,

Bunka shūreishū 文華秀麗集, and

Keikokushū 經國集. The compilation of the three imperial anthologies of Chinese poetry was an undertaking that symbolized an “Era of Chinese-style poetry.” This background, alongside the progress of the

ritsuryō state system, includes the expansion of an aristocratic and bureaucratic class capable of composing

kanshi. Additionally, even more so than in the era of

Kaifūsō, there was an even stronger awareness of

kanshi as a literary marker of a nation that belonged to the East Asian Sinorgaphic sphere. By that time, the Tang dynasty had already entered the later stage of the mid-Tang period. While three imperial

kanshi anthologies reflect the reception of mid-Tang poetry, they inherited the poetic style of the Qi and Liang periods of the Southern Dynasties. While it is possible to find some influence of mid-Tang poetry in the three

kanshi anthologies, they continue the style inherited from Qi and Liang poetry, while the influence of the early Tang style is much more apparent. However, compared with

Kaifūsō, the standard of poetry composition improved, and a unique world of

kanshi began to emerge in Japan. Yoshifumi Hangai 半谷芳文’s

Research on the Three Imperial Anthologies of Chinese Poetry ÂãÖÊí∞‰∏âʺ¢Ë©©ÈõÜ„ÅÆÁÝîÁ©∂ (Kenbun Publishing, 2022) highlights this phenomenon. One example is how the three poems ‚ÄúRespectfully offering a poem harmonizing with the topic ‚ÄòLament of the Spring Bedchamber‚Äô‚Äù •âÂíåÊò•Èñ®ÊÄ® by Sugawara no Kiyotomo ËèÖÂéüÊ∑∏ÂÖ¨, Asano no Katori ÊúùÈáéÈπøÂèñ, and Kose no Shikihito Â∑®Âã¢Ë≠ò‰∫∫ ‚Äúdepict the emotions and demeanor of ‚Äòthe woman.‚Äô The portrayal of the ‚Äòwoman‚Äô in all three compositions presents a beauty that extends also to the figure of the ‚Äòwaiting woman‚Äô who appears in Heian-era kana literature, and in this we can already note a unique quality to Japanese

kanshi poets’ compositions.

2 Another example is the phenomenon where the seven-character regulated verse was independently created during the reign of Emperor Saga and later became a prominent poetic form of Japanese

kanshi during the middle and later parts of the Heian period.

3

Furthermore, after the mid-Heian period, when the seven-character regulated verse became widespread, a unique style of Japanese

kanshi was born. This style is called

kudaishi 句題詩 (topic poetry).

4 In this style, a poem’s title is created by using a five-character phrase containing two nouns (this is called the “

kudai”), and the poem is composed following certain rules in the form of a seven-character regulated verse. Detailed information about

kudaishi can be found in Michio Satou’s 佐藤道生

Kudaishi Study Âè•È°åË©©Ë´ñËÄÉ (Bensei shuppan ÂãâË™ÝÂá∫Áâà, November 2016). According to Satou‚Äôs research,

kudaishi was a poetic style invented by Sugawara no Fumitoki 菅原文時 (899-981), who was active during the reign of Emperor Murakami (946–967). It was widely practiced among the aristocracy, extending into the Kamakura period. The rules for this style dictate that in the first couplet, the

kudai is used to express the meaning of the title; in the second and third couplets, the meaning of the title is expressed without using the five characters in the title; the poem concludes with the author expressing their thoughts in the final couplet.

Around the middle of the Heian period, when uniquely Japanese seven-character regulated verses and kudaishi were flourishing, the influence of famous poet Bai Juyi’s 白居易 (772-846) works was overwhelming. However, by the Kamakura period (1185–1333), Zen Buddhism, Zhu Xi’s philosophy, and Song Dynasty poetry and prose were transmitted from China, and the main class of people producing kanshi starkly shifted from aristocrats to Zen monks. Later, at the end of the Muromachi period (1336–1573), monks at influential Zen temples in Kyoto and Kamakura—known as “The Five Mountains and Ten Monasteries”—further expanded Chinese literature and gozan bungaku (五山文學, “Five Mountains literature”). Needless to say, this important time in the history of Chinese literature in Japan has been the subject of copious amounts of research. Among Chinese poets, Su Shi and Huang Tingjian were particularly revered. Du Fu 杜甫, who greatly influenced both of them and was venerated as a patriarch by the Jiangxi Poetry School 江西詩派, which revered Huang Tingjian, was likewise held in high regard.

As will be mentioned later, the full reception of Du Fu in Japan began during the era of

gozan bungaku. Then, in the Muromachi period, lectures on Du Fu, along with those on Su Shi 蘇軾 (1037-1101) and Huang Tingjian’s poetry, began to be given by Zen monks, the results of which were written down and became what is known as

shōmono 抄物 (“excerpts”). The writing styles of

shōmono include

kanashō 假名抄 (written in hiragana and/or katakana),

kanbunshō 漢文抄 (written in Literary Sinitic), as well as

shōmono that mixes Japanese and Chinese writing.

Kanashō uses colloquial language that would be used in verbal speech, and valuable results have been achieved as research advances on these materials in the study of medieval Japanese. Therefore, traditional research on

shōmono has largely focused on this aspect, especially

shōmono on Chinese texts. Although they should be considered the mainstream of

shōmono, they have remained confined to the field of medieval oral language studies. However,

shōmono on Huang Tingjian has finally begun to be examined from the perspective of Chinese literary studies.

5

To understand how the Japanese interpreted Chinese texts based on historical documents, the main option was to rely on annotations such as kunten 訓點 (marks that aid in reading comprehension) added by the hereditary scholar families 博士家 and other scholars before the emergence of gozan bungaku shōmono. Shōmono were the written results of Zen monks' meticulous readings of Chinese text, establishing themselves as Japan’s first interpretative works in the history of Japanese Sinology.

Several examples have been presented of Japanese kanshi since the creation of the previously mentioned Kaifūsō from the perspective of its distinctiveness throughout different periods. However, it can be said that shōmono held a unique significance in the Muromachi period. In recent years, research has focused on shōmono as sources of lost Chinese texts, but studies of shōmono should instead focus on their role as interpretative texts—as records of how Zen monks of the gozan tradition read and interpreted Chinese texts. With this in mind, I will now introduce the shōmono written on Du Fu.

The Reception of Du Fu’s Poetry up to the Early Period of Gozan Bungaku

In the List of Writings Currently Held in the Nation of Japan 日本國現在書目録, compiled by Fujiwara no Sukeyo 藤原佐世 (847-897) in 889 (Kanpyō 1) by imperial order, which records the Chinese classics held in the imperial archives during the early Heian period (794–1184), we find collections of poetry by High Tang poets such as Wang Wei ji 王維集, Wang Changling ji 王昌齡集, Li Bai gexing李白歌行. Also listed are Mid-Tang works such as the Baishi wenji 白氏文集Baishi Changqing ji 白氏長慶集, and Yuanshi Changqing ji 元氏長慶集. However, no collection of Du Fu’s poetry is recorded, suggesting that his work had not yet been received or recognized in Japan at that time.

Later, in the latter half of the tenth century, six couplets of Du Fu were selected and compiled in Senzai Kaku 千載佳句 by Ōe no Koretoki 大江維時 (888–963), thus solidifying the clear reception of Du Fu’s poetry in Japanese literary culture. During this period, the works of Bai Juyi were widely circulated, and since Bai Juyi held Du Fu in high regard, it is possible that the people of the mid-Heian period began to take notice of Du Fu’s poetry, as well. The immense influence of Bai Juyi’s literature continued into the early Kamakura period (1185–1333), but in its later years, the creation of kanshi by Zen monks influenced by the literature of the Song and Yuan dynasties began to flourish, marking the beginning of the era of gozan bungaku in medieval Japan. As previously noted, among the Zen monks of the Gozan temples, the poetry of Su Shi and Huang Tingjian was especially favored. Tracing back from Su and Huang, monks also came to study the poetry of Du Fu, whom both poets held in high esteem. This contributed to the deepening reception of Du Fu’s poetry in Japan.

Zen literary traditions centered on Kamakura and Kyoto

gozan continued beyond this period, spanning the Northern and Southern Courts period (1336–1392), the Muromachi period (1336–1573), and into the early Edo period (1603–1868). The development of

gozan bungaku is generally divided into three phases: the early phase up until the Nanboku-chō period, the middle phase from the early Muromachi period until around the time of the Ōnin War (1466–1467), and the last phase thereafter.

6

The first Japanese Zen monk whose engagement with Du Fu’s poetry is notable during the early phase of

gozan bungaku is Kokan Shiren 虎關師錬 (1278–1346), who is known as the “founder” of

gozan bungaku.

7 In Volume 11 of Kokan Shiren’s

Saihokushū 濟北集 titled

Poetry Talks Ë©©Ë©±, he discusses four of Du Fu‚Äôs poems: ‚ÄúAscending Yueyang Tower‚Äù ÁôªÂ≤≥ÈôΩÊ®ì, ‚ÄúThe Thatched Study of Reverend Si‚Äù È°åÂ∑≥‰∏ä‰∫∫ËåÖÈΩã, ‚ÄúParting from Reverend Zan‚Äù Âà•Ë¥ä‰∏ä‰∫∫, and ‚ÄúSentiment at Kui Prefecture‚Äù ËôÅÂ∫úË©ÝÊá∑‰∏ÄÁôæÈüª. In his analysis of ‚ÄúAscending Yueyang Tower,‚Äù Kokan Shiren critiques a proposed interpretation of the line, ‚ÄúThe days and the nights float over Heaven and Earth.‚Äù (‰πæÂù§Êó•Â§úʵÆ) He believes a commentator incorrectly interpreted this line as ‚ÄúDongting Lake exists within the heavens and the earth, and its water floats day and night,‚Äù while Kokan Shiren argues a more accurate interpretation would be ‚ÄúDongting‚Äôs vastness is well-suited to float amongst Heaven and Earth.‚Äù In his analysis of ‚ÄúThe Thatched Study of Reverend Si,‚Äù Kokan Shiren corrects a commentator who citing Ouyang Xiu Ê≠êÈôΩ‰øÆ (1007-1072), mistakenly identifies ‚ÄúMaster Si‚Äù as Qiji ÈΩäÂ∑± (863-937), a poet who lived nearly a hundred years after Du Fu. In ‚ÄúParting from Reverend Zan,‚Äù he points out that the lines ‚ÄúIn the morning a willow branch is in his hand, his beans have ripened in the rain‚Äù (Ê•äÊûùÊô®Âú®Êâã, ˱ÜÂ≠êÈõ®Â∑≤ÁÜü) are a reference to the

Fanwang jing 梵網經, and he criticizes the omission of the full citation of the

Fanwang jing by scholar Huang Xi 黄希, who only mentions the first part of the line. At the end, he remarks, “One can see the refinement or coarseness of poetic thought. Judging from this, among the many commentators, those who have truly ascended the altar of Du Fu are few indeed,” thereby criticizing the annotations of various scholars, including Huang Xi and his son Huang He in the

Ji qianjia zhu fenlei Du Gongbu shi 集千家註分類杜工部詩集, a collection of commentaries on Du Fu’s poems. Regarding “Sentiment at Kui Prefecture,” Kokan Shiren argues that the commentator’s interpretation of the phrase “knocked at the Chan gate of the Seven Patriarchs,” (門求七祖禪) reading “Seventh Patriarch” (七祖) as “Seven Buddhas” (七佛) is a laughable misunderstanding. He provides textual evidence to identify the reference instead as Puji 普寂(651-739), the Dharma heir of Shenxiu 神秀(606-706) of the Northern Chan school. The commentaries on these four Du Fu poems that Kokan Shiren discussed in

Poetry Talks all appear in the

Ji qianjia zhu fenlei Du Gongbu shi, suggesting that Kokan Shiren read Du Fu’s poetry through this collection. Kokan Shiren’s ability to critique preexisting Chinese annotations demonstrates his exceptionally detailed and precise reading of Du Fu’s poems. Therefore, Kokan Shiren is not only the “founder” of

gozan bungaku, but he also paved the way for the study of Du Fu’s poetry in Japan.

Another figure, Chūgan Engetsu 中巖圓月 (1300–1375) examined a claim made about Du Fu in his poetry commentary Tōin Sasai-shū 藤陰瑣細集. The claim was originally made in The New Book of Tang and stated that Du Fu died in Leiyang after becoming “heavily intoxicated.” However, using an alternative theory from Li Guan 李觀’s “Supplement to the Biography of Du Zimei” 遺補杜子美傳 and a poem written by Han Yu 韓愈 (768-824) “Inscription on Du Zimei’s Tomb” 題子美墳, Chūgan Engetsu demonstrated that the assertion made in The New Book of Tang was false. Moreover, in Chūgan Engetsu’s poetry collection entitled Tōkai Ichiō-shū 東海一漚集, we can find evidence of Du Fu’s influence. In Volume 1, for example, there are several poems related to Du Fu, including a five-character old style poem titled “After Casually Reading Du Fu’s Poetry, I Was Moved and Composed My Own,” 偶看杜詩有感而作 a seven-character quatrain titled “One Morning in March, I Was Moved After Hearing a Child Recite Du Fu’s Verses” 三月旦聽童吟杜句有感 and a five-character regulated verse titled “Imitating Old Du: A Playful Composition.” 效老杜戲作俳偕體 These works all exemplify the true embracement of Du Fu’s poetry.

Edited by Kankō Uemura, Gozan bungaku zenshū 五山文學全集 Saihokushū 濟北集 Volume 11, shihua

Gid≈ç Sh≈´shin Áæ©ÂÝÇÂ뮉ø° (1325‚Äì1388), a disciple of Mus≈ç Soseki §¢Á™ìÁñéÁü≥ (1275-1351, was also influenced by Ch≈´gan Engetsu), wrote in his work ‚ÄúPreface to a Poem for Master Xiu‚Äù Ë¥àÁßĉ∏ä‰∫∫Ë©©Â∫è (found in Volume 11 of K≈´gesh≈´ Á©∫ËèØÈõÜ), ‚ÄúAmong those skilled in poetry from the Tang dynasty, none surpass Du Fu,‚Äù thereby giving Du Fu the highest praise. Furthermore, Gid≈ç Sh≈´shin was deeply moved by a line from Du Fu‚Äôs poem ‚ÄúPresented to Sheriff Liu of Huayang‚Äù Ë≤ΩËèØÈôΩÊü≥Â∞ëÂ∫ú: ‚ÄúLiterary composition is but a minor skill; it is not esteemed in the context of the Way‚Äù ÊñáÁ´Ý‰∏ÄÂ∞èÊäÄ„ÄÅÊñºÈÅìÊú™Áà≤Â∞ä. This resonated with his belief that the realization of Zen enlightenment was of highest importance, and that literature was merely a method to express such state of mind. He articulated this literary perspective in ‚ÄúJin River Discourse: Bidding Farewell to Reverend Ji as He Returns Home‚Äù Èå¶Ê±üË™¨ÈÄÅÊ©ü‰∏ä‰∫∫Ê≠∏Èáå from K≈´gesh≈´ Volume 16, stating: ‚ÄúIndeed, the Way is the foundation of learning, while literature is secondary.‚Ķ Even Old Du, who took great pride in his literary achievements, did he not say, ‚ÄòLiterary composition is but a minor skill; it is not esteemed in the context of the Way‚Äô Truly something to think about!‚Äù This way of thinking had a strong influence on literary perspectives within the Zen community.

Zekkai Chūshin 絶海中津 (1336-1405) was honored with the title of “National Preceptor Shōtei” 勝定國師 and, together with Gidō Shūshin, they were praised as the “two jewels” of gozan bungaku.

In 1368, Zekkai traveled to Ming China and became a disciple of Jitan Zongle 季潭宗泐 (1318-1391) at the Zhongtianzhu 中天竺 Temple, where he also received teachings on Du Fu’s poetry. As noted later, in Volume 4 of Kōsei Ryūha’s 江西龍派

Toshi Zokusuish≈ç ÊùúË©©Á∫åÁøÝÊäÑ, under the annotation for the second poem of ‚ÄòRespectfully Accompanying Escort Zheng in Weiqu,‚Äô •âÈô™ÈÑ≠Èßôȶ¨ÈüãÊõ≤‰∫åȶñ specifically the line beginning with ‚Äò‰ΩïÊôÇ‚Äô (which should be read as ‚Äò‰∫ã‚Äô), it states that Zekkai ‚Äúreceived teachings from Jitan,‚Äù indicating the transmission of Du Fu scholarship from Jitan to Shengding. It is recorded in

Gaun Nikkenroku Batsu-yū 臥雲日件録拔尤, the diary of Zuikei Shūhō 瑞溪周鳳 (1391–1473), a third-generation disciple of Zekkai Chūshin, dated 10

th day of the fifth month 1453, that, according to hearsay from Ten’ei Shūken 天英周賢 Zekkai Chūshin and his successor, Gempuku Ekō 元璞慧珙, had a conversation regarding the interpretation of a phrase from Du Fu’s poem, “To Pei, Upon Hearing that Judge Yuan Came and Wanted to Investigate.” 贈裴南部聞袁判官自來欲有按問 Zekkai Chūshin suggested that in the line, “Emerging at once, the yellow sand appears” (即出黄沙在), the character

chu (出), meaning “to come out,” should instead be read as

qu (屈), “to bend” or “to yield.” This further illustrates how Zekkai was actively engaging in teaching interpretations of Du Fu’s poetry. Although the details of Zekkai’s lectures on Du Fu’s poetry remain unclear, Takami Saburo 高見三郞 mentions that there are quotations of Zekkai’s interpretations in Kōsei Ryūha’s

Toshi Zokusuishō that were conveyed through his disciple Taihaku Shingen 太白眞玄.

8 In Setsurei Eikin’s 雪嶺永瑾 (1447-1537)

Toshi shō 杜詩抄―, the phrase “National Preceptor Shōtei says” (勝定國師云) is also frequently cited, and there are instances when interpretations not found in

Toshi Zokusuishō are referenced (for example, in Volume 3, “Hokusei” 北征). In

Toshi Zokusuishō Volume 4 (in the section “Going Late out the Left Palace Gate” 晚出左掖– “Riding a Horse 1” 騎馬ー), it is noted that “National Preceptor Shōtei used annotations,” 勝定國師用批語 This suggests that Zekkai Chūshin read Du Fu’s poetry using

Ji qianjia zhu pidian Du Gongbu ji 集千家註批點杜工部集, edited by the Yuan-period scholar Gao Chonglan (高崇蘭, courtesy name Chufang 楚芳) who based his work on the Southern Song edition with Liu Chenweng’s 劉辰翁 annotations. It is said that the reception of Du Fu’s collected works in the Zen community shifted from the

Ji qianjia zhu fenlei Du Gongbu shi 集千家註分類杜工部詩 during Kokan Shiren’s era to the

Ji qianjia zhu pidian Du Gongbu ji 集千家註批點杜工部集 in Zekkai’s era.

9 There was a gozan edition of

Ji qianjia zhu pidian Du Gongbu ji, which was a reprint of the 1368 edition published by Yunqu Huiwentang Èõ≤Ë°¢ÊúÉÊñáÂÝÇ from the Nanbokuch≈ç period, and this edition became widely circulated.

Shōmono on Du Fu’s Poetry During the Middle Period of Gozan Bungaku

Zekkai Chūshin’s lectures on Du Fu’s poetry were never fully compiled by his disciples, but during the middle period of gozan bungaku, commentaries on Chinese classics and Buddhist texts began to be produced in various forms, such as lecture records, outlines, and memorandum texts. These texts related to Zen lectures are referred to as “shōmono,” or “excerpts.” Many shōmono were created by Zen monks from Kyoto Gozan, but there were also works done by scholar families (such as the Kiyohara 淸原 family, hereditary scholars of Myōgyōdō 明經道), and the subjects ranged from Japanese classics such as the Chronicles of Japan 日本書紀 to medical texts. The texts were often written in Literary Sinitic, but the use of a more colloquial style using kana can also be seen, and sometimes a mix of both Literary Sinitic and kana was used. Since shōmono are often written in colloquial speech, they have been used as linguistic sources for studying the Japanese language during the Muromachi period. However, in recent years, their use as research materials for studying Chinese classics has also increased.

Since Du Fu‚Äôs poetry was highly valued in Zen circles, it naturally became a subject of sh≈çmono. The earliest of this type of work is considered to be Shinge okudan ÂøÉËèØËáÜÊñ∑ by Shinge Gentei ÂøÉËèØÂÖÉÊ££ (birth and death years unknown). Shinge okudan was mentioned by Ten‚Äôin Ry≈´taku (§©Èö±ÈæçÊæ§, 1423‚Äì1500) in his work Mokugun k≈ç ȪòÈõ≤Á®ø, where he wrote: ‚ÄúIn our country‚Äôs Zen community, senior monks such as Dainen §ßÂπ¥ (Á••Áôª), Shinge ÂøÉËèØ, and Taihaku §™ÁôΩ have provided extensive oral interpretations. How many have preserved these notes in their drawers or desks? Among them, only Shinge okudan, along with Liu shi pingdian ÂäâÊ∞èË©ïȪû(Liu Chenweng‚Äôs Annotated Edition) have flourished in this world.‚Äù It surpassed the commentaries of monks like Dainen Sh≈çt≈ç and Taihaku Shingen, and it is known that it was widely accepted throughout the Zen community, along with Liu shi pingdian. However, Shinge okudan now only exists in excerpts found in later works such as K≈çsei Ry≈´ha‚Äôs Toshi Zokusuish≈ç ÊùúË©©Á∫åÁøÝÊäÑ, Jinro Seiju‚Äôs ‰ªÅÁî´ËÅñÂØø Zokuokudan Á∫åËáÜÊñ∑ and Setsurei Eikin‚Äôs Toshi sh≈ç. In recent years, scholar Toru Ota has researched Shinge okudan using Toshi Zokusuish≈ç and Toshi sh≈ç as the main materials. (As the existence of Zokuokudan was only recently confirmed, it was not included in his research.) His findings were published in the paper ‚ÄúOn the Shinge okudan, a Commentary on Du Fu's Poetry: The Characteristics of Commentary on Du Fu's poetry in the Japanese Zen Monastic Tradition ‚Äù ÊùúË©©Ê≥®ÈáãÊõ∏„ÄéÂøÉËèØËáÜÊñ∑„Äè„Å´„ŧ„ÅфŶ‚ÄïÊó•Êú¨Á¶™Êûó„Å´„Åä„Åë„ÇãÊùúË©©Ê≥®Èáã„ÅÆÊ®£Áõ∏‚Äï in Nihon Ch≈´gokugakkai h≈ç, Volume 54 (2002). According to this, Shinge okudan is cited in 206 poems in the Toshi Zokusuish≈ç and appears in approximately 400 poems in the Toshi sh≈ç. The former cites summaries of the text, while the latter generally quotes the commentary verbatim. It also mentioned that through these two works, we are able to see four distinctive features of Shinge‚Äôs annotation methods, which are: 1) the division of annotations into sections 2) the structural analysis of poems, couplets, lines, and characters 3) the analysis of allusions and 4) conjectural interpretations. In point 1, the method of annotation based on the dividing into sections from Mu Tian Jin Yu Êú®Â§©Á¶ÅË™û by Fan Deji ËåÉÂæ∑Ê©ü (1272-1330) of the Yuan dynasty is adopted. Point 2 makes it clear that it incorporates the ‚Äúpoetic form‚Äù Ë©©Êݺ from the Yuan dynasty-era poetry discourse Shi Fa Yuan Liu Ë©©Ê≥ïÊ∫êʵÅ. As for point 3, it reveals the vast knowledge of classical allusions that were not cited by Song dynasty commentators. However, it sometimes crosses the line into over- interpretation, which was notably criticized by K≈çsei Ry≈´ha. The conjectural interpretation (point 4) is what the title ‚Äúokudan‚Äù (‚ÄúSpeculations‚Äù) refers to in Shinge okudan, and it is also said that K≈çsei Ry≈´ha and Setsurei Eikin have criticized this approach to poetry. An example of this criticism can be seen in the interpretation of the opening lines, ‚ÄúThe Left Aide is often an empty position, this year they got an seasoned Confucian scholar.‚Äù (Â∑¶ËΩÑÈݪËôö‰Ωç, ‰ªäÂπ¥ÂæóËàäÂÑí) of Du Fu‚Äôs poem, ‚ÄúPresented to Wei Ji, Vice-Director of the Left‚Äù Ë¥àÈüãÂ∑¶‰∏ûÊøü that is cited by K≈çsei Ry≈´ha in his Toshi Zokusuish≈ç.

Shinge says, “If there is no suitable person, then it is as if the post remains vacant even if someone holds the position. Now that they no longer follow the proper methods, even unworthy men occupy official positions. If the current occupant of the position of Left Aide were a virtuous man, even then he should be removed to place Lord Wei in that role. How much more so if the current occupant is not a good man? All the more, he ought to be removed. This Wei is a virtuous person, a gentleman.” In response to this interpretation by Shinge, Kōsei Ryūha criticized it as “too far-fetched,” and quoted Zekkai Chūshin (National Preceptor Shōtei), who said, “Those who have been in the position of the Left Aide in the past have not been virtuous people. Therefore, although they were in that position, it was as if the position was vacant. Now, with Wei, the position is filled by the right person, and the position and person are truly well matched— moreover, he is a seasoned Confucian scholar.” Kōsei agreed with Zekkai’s clear interpretation, calling it “simple and acceptable.” Setsurei Eikin’s Toshi shō incorporates all passages from Zokusuishō. Another aspect that can be understood upon viewing this quotation in its original form is how both Shinge okudan and Zokusuishō use a style of writing that combines Literary Sinitic with kana-based colloquial expressions. The same is also true of Toshi shō.

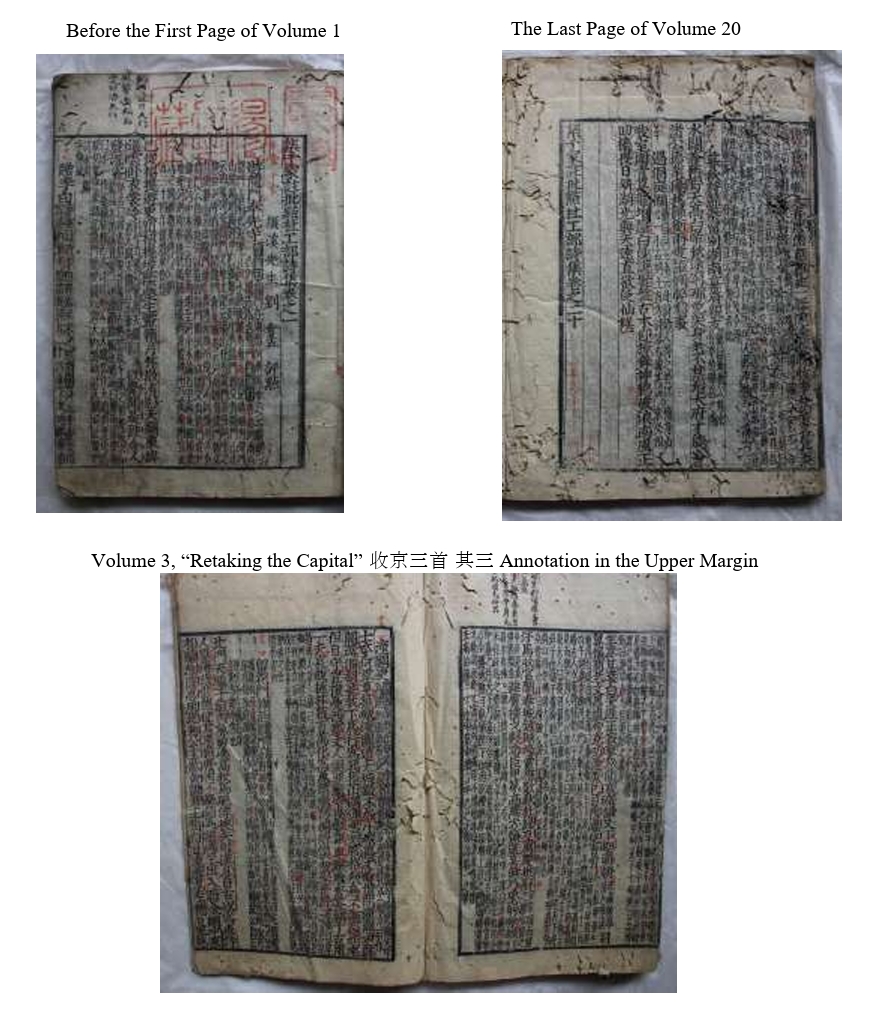

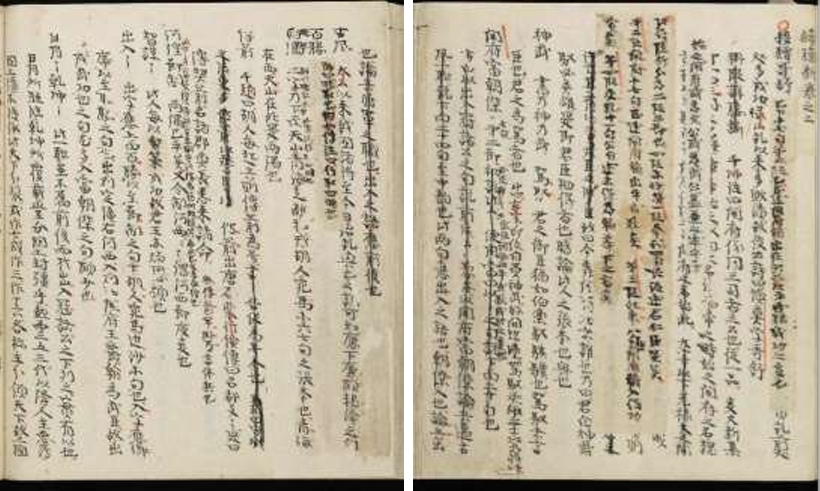

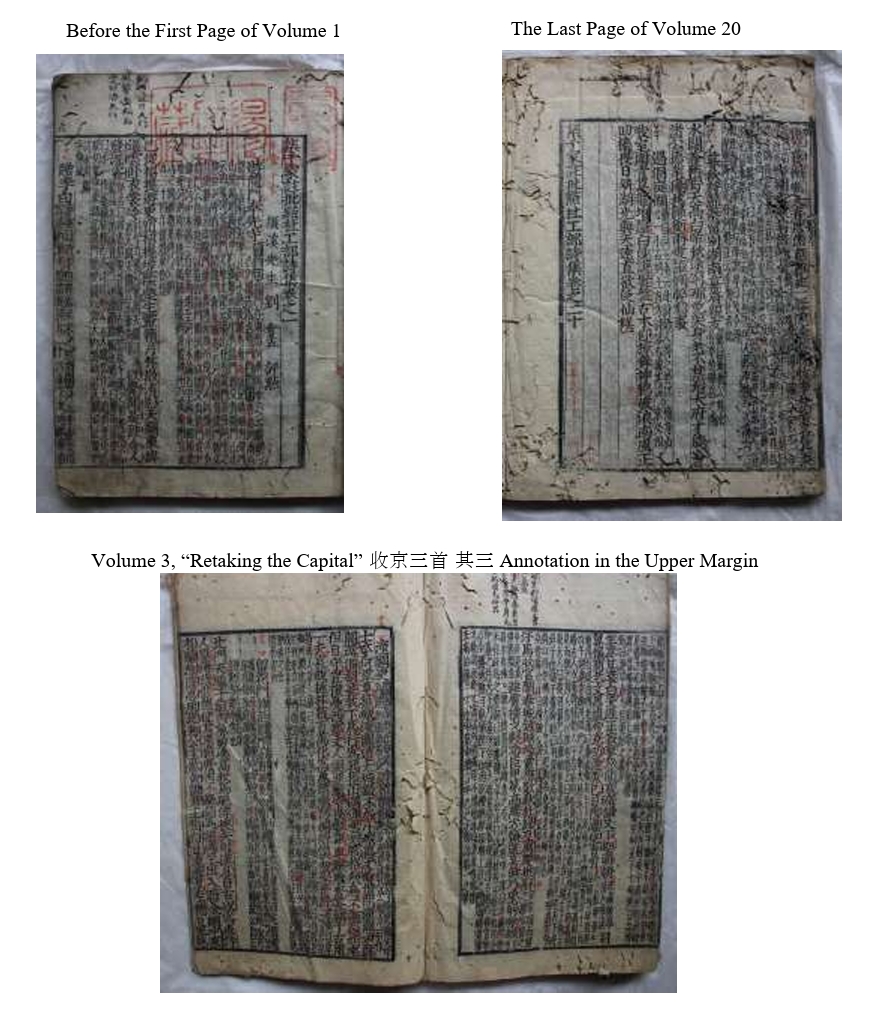

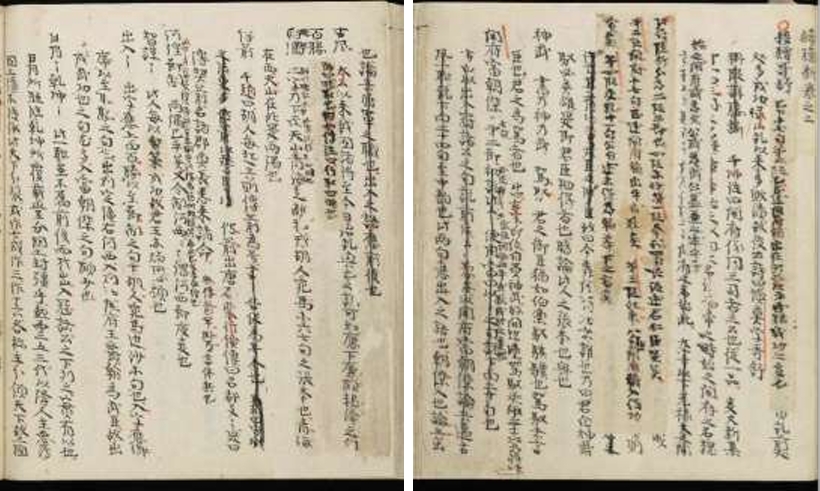

Although Shinge okudan has been lost, making it impossible to see the full scope of Shinge’s annotations on Du Fu’s poems, some materials remain that provide insight into how he interpreted the original text. Such material consists of detailed kunten annotations in red ink (sometimes also including black-ink annotations) that were added to the 20-volume gozan edition of Ji qianjia zhu pidian Du Gongbu ji, which is stored in Yōmei Bunko 陽明文庫 archives in Kyoto. At the end of Volume 20, a note written in red ink states, “Shinge has added reading marks” (心華點寫了) indicating Shinge’s comprehension of the original poems via these kunten. However, since the note does not explicitly say “Shinge marked this” (心華點了), it is thought that these marks were transcribed by someone else down the line rather than being written by Shinge himself. An excerpt in Zokusuishō Volume 7 analyzes the line, “He carried back in hand to toss it to Grand Master Cui” (手提擲還崔大夫) from the poem “A Song for Lord Hua Playfully Written” 戲作花卿歌. Regarding the reading of this line, Shinge’s annotations read the two characters ti 提 and zhi 擲 (lifting and throwing) as a single word, thus interpreting the meaning as “holding it in your hands and sending it back to Grand Master Cui [as one action]” 提擲して. The kunten on the right side in the Yōmei Bunko version specifically reads “taking it in hand and sending it back to Grand Master Cui,” while “lifting and throwing it away” is marked with red ink on the left side. In these annotations, tizhi 提擲 is written as a single word (提擲する), which is consistent with Shinge’s annotations, therefore proving that these kunten are a transcription originally belonging to Shinge. It is known that Shinge added kunten to Du Fu’s selections, as later mentioned in the self-preface of his disciple's disciple, Jinro Seiju’s Zokuokudan, which states, “Master Shinge, the Great Zen Master, in his leisure time after his Zen chanting, used kana to mark the three collections of Du Fu, Han Yu, and Liu Zongyuan 柳宗元 (773-819).” Therefore, it is safe to say that the Yōmei Bunko version is a valuable source that passed down Shinge’s annotations.

The Yōmei Bunko version contains not only kunten of the texts, but also numerous notes written in red and black ink. In Volume 3 of Zokusuishō, there is an annotation regarding the line “Federate barbarians’ brandished pikes are thick” (雜虜橫戈數) from “Retaking the Capital” 收京三首 that states, “In the Strategies of the Warring States 戰國策, the envoy of Wei, Zhu Guo removes his helmet, brandishes his spear, and advances. This was originally referenced by Shinge.” In the upper margin of this poem in the Yōmei Bunko version, this same phrase “In the Strategies of the Warring States … he advance with brandished spears” is written in black ink, which can be considered the documentation of Shinge’s annotations. Additionally, regarding the phrase “sacred body” 聖躬 in the last poem, there is a red ink annotation in the upper margin that reads: “From Kong Rong’s biography孔融傳 in the Book of the Later Han 後漢書: ‘The ruler of a myriad chariots is of great weight, the Lord of Heaven is supreme, his body is sacred, and the country is a sacred vessel.’” This annotation is also thought to be that of Shinge’s. Together with the note on the Strategies of the Warring States, this shows a historical allusion not found in the Song dynasty annotations. Further research is awaited on the Yōmei Bunko version of Shinge’s annotations.

Shinge’s annotations stored in Yōmei Bunko, Gozan Edition of Ji qianjia zhu pidian Du Gongbu ji 集千家註批點杜工部集

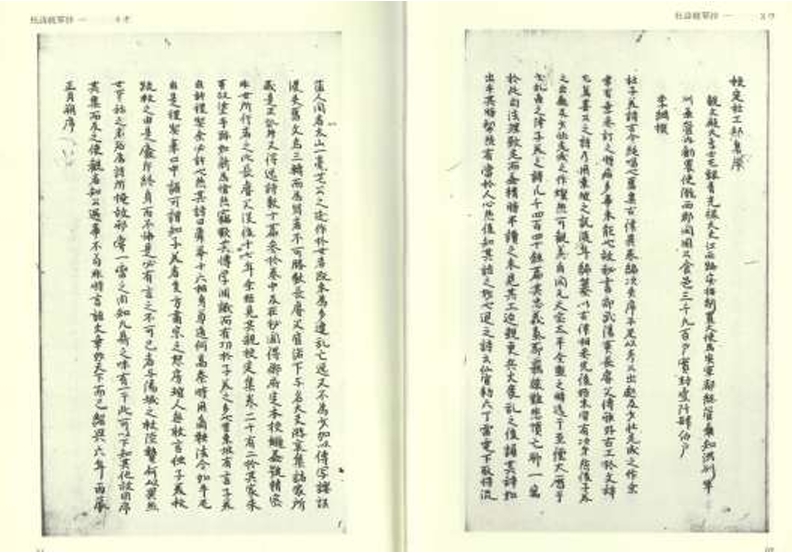

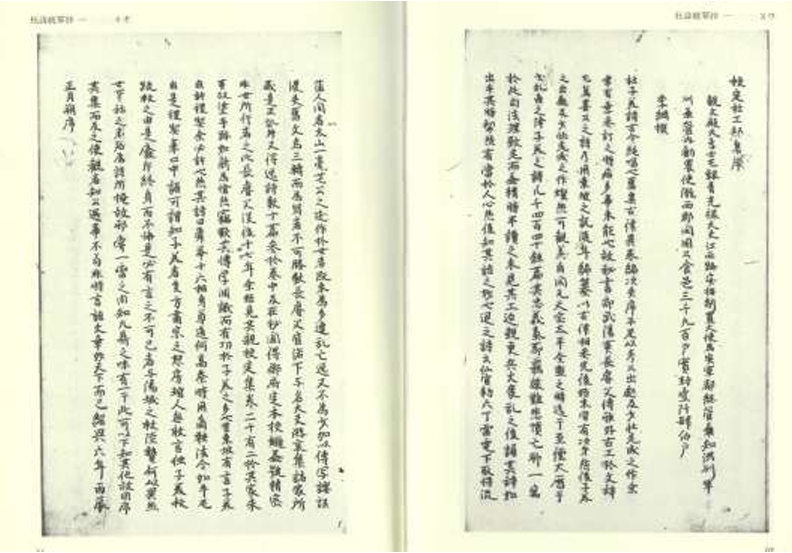

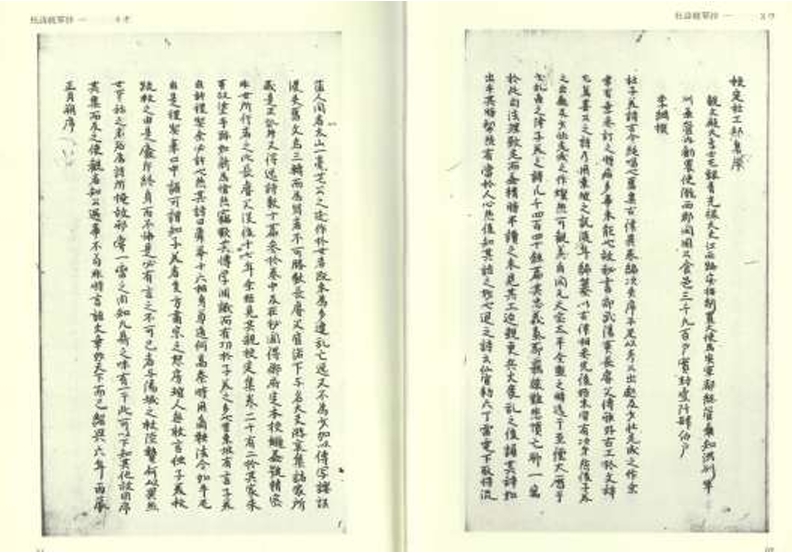

The oldest surviving sh≈çmono of Du Fu‚Äôs poetry is the Toshi Zokusuish≈ç (abbreviated as Zokusuish≈ç) by K≈çsei Ry≈´ha, as mentioned earlier. K≈çsei retired to the Zokusui-ken Á∫åÁøÝ˪í at Kenninji Temple ª∫‰ªÅÂØ∫, which is why he is also known by the alias Zokusui (he was also called Hin‚Äôan˱©Ëè¥), and this book‚Äôs title originates from his alternate name. Zokusuish≈ç is said to have been compiled by Shukuei Shin‚Äôy≈ç ÊñáÂèîÁúû˶Š(birth and death dates unknown) from K≈çsei‚Äôs lectures (according to the previously mentioned paper by Saburo Takami). The Kenninji Ryosokuin ª∫‰ªÅÂØ∫ÂÖ©Ë∂≥Èô¢ (with missing Volumes 1, 2, and 20, and Volume 18 partially missing) and the National Diet Library ÂúãÊúÉÂúñÊõ∏ȧ® hold copies of Zokusuish≈ç, with the latter being a re-copied edition from the Edo period based on the former. A facsimile of the Ry≈çsokuin version is included in Zoku sh≈çmono Shiry≈ç Sh≈´sei Á∫åÊäÑÁâ©Ë≥áÊñôÈõÜÊàê (published by Seibund≈ç Shuppan Ê∑∏ÊñáÂÝÇÂá∫Áâà, 1980), with Volumes 1 and 2 supplemented by the National Diet Library version.

Zokusuish≈ç is a sh≈çmono by K≈çsei Ry≈´ha, which uses Ji qianjia zhu pidian Du Gongbu ji as its primary text. It extensively examines commentaries from the Song and Yuan dynasties, as well as annotations from Liu Chenweng and various Japanese scholars such as Zekkai Ch≈´shin, Dainen Sh≈çt≈ç, and Shinge Gentei. Zokusuish≈ç is a sh≈çmono that was compiled to present author‚Äôs views based on these commentaries. As for Song dynasty annotations, apart from those from the primary text, Ji qianjia zhu pidian Du gongbu ji, it also cites annotations from Ji qianjia zhu fenlei Du Gongbu shi, also referred to as senka ÂçÉÂÆ∂. It often uses annotations from Cai Mengbi Ëî°Â§¢Âºº‚Äôs edited version of Du gongbu caotang shijian ÊùúÂ∑•ÈÉ®ËçâÂÝÇË©©ÁÆã (using the modified 40-volume edition with 10 supplementary volumes, rather than the original 50-volume edition), and it occasionally cites the early Ming dynasty work Du Du shi yu de ËÆÄÊùúË©©ÊÑöÂæó by Shan Fu ÂñÆÂæ©.

Moreover, as pointed out by Saburo Takami, the main text‚Äôs notes sometimes cite something called ‚Äúrevision‚Äù ÊÝ°ÂÆö.

10 For example, regarding the word ‘

hu’ (壺) in the line ‘Magnificent indeed is the painting of Mount Kunlun and Fanghu’ (壯哉崑崙方壺圖) from the poem ‘A Playful Inscription on Wang Zai’s Landscape Painting’ 戲題王宰畫山水圖歌, it notes in the commentary: ‘correction:

hu(壺) should be

zhang(丈)’ (

Zokusuishō, Volume 7). Before the main text of

Zokusuishō Volume 1, the preface to

Jiaoding Du Gongbu ji ÊÝ°ÂÆöÊùúÂ∑•ÈÉ®ÈõÜ is included. This preface was attached to the

Jiaoding Du Gongbu ji, which was edited by Huang Bosi 黄伯思 (1079–1118) of the Northern Song dynasty. The long official title that includes the author’s name is, “Guanwen dian xueshi Zuo Yinqing Guanglu dafu Jiangxi lu anfu zhizhì dashi mabu jun du zongguan jian zhi Hongzhou jun zhou jian guannei quannongshi Longxi jun kaiguo gong shiyi san qian jiu bai hu, shifeng yi qian si bai hu, Li Gang zhuan” 觀文殿學士左銀靑光祿大夫江西路按撫制置大使馬歩軍諸總管兼知洪州軍州兼管内勸農使隴西郡開國公食邑三千九百戸實封壹仟肆伯戸李綱撰. The main text concludes with “Shaoxing liunian zhengyue shu xu” 紹興六年 (1136) 正月朔序.

Jiaoding Du Gongbu ji was published at the beginning of the Shaoxing era by Huang Bosi’s son, Shang 裳. After it was brought to Japan, it is thought that Kōsei Ryūha used it to write annotations with alternative readings of the text.

Jiaoding Du Gongbu ji, consisting of 22 volumes, has become a lost work in China, but the full text of Li Gang ÊùéÁ∂±‚Äôs preface has been preserved in his ‚ÄúChong jiaozheng Du Zimei ji xu‚Äù ÈáçÊÝ°Ê≠£ÊùúÂ≠êÁæéÈõÜÂ∫è in the

Liangxi ji 梁谿集, Volume 138 (Siku Quanshu edition 四庫全書本), and can also be found in

Dongguan yulun 東觀餘論, juan xia 卷下 (

Guyi congshu 古逸叢書, third series, Jiading 3rd year edition reprint 影印嘉定三年刻本). Since the original text has been lost, its contents cannot be viewed directly. However,

Zokusuishō preserves fragments of it, which makes

Zokusuishō as work extremely valuable. It is also worth noting that the ‘Preface to the Re-corrected Collected Works of Du Fu’ in the

Liangxi ji dates the composition to ‘the first day of the sixth month of the fourth year of Shaoxing, cyclical year jia-yin (1134),’ among other textual discrepancies. The version of the preface found in

Zokusuishō belongs to the textual lineage of the version included in

Dongguan yulun.”

Kōsei Ryūha’s Toshi Zokusuishō cites Li Gang’s “Chong jiaozheng Du Zimei ji xu” (as reproduced in the National Diet Library version of Zoku Shōmono Shiryō Shūsei)

Toshi Zokusuishō, 巻三首 (Reprinted from ryosokuin 兩足院 version in Zokushōmono shiryō shūsei)

Shōmono on Du Fu’s Poetry in the Late Period of gozan bunkaku

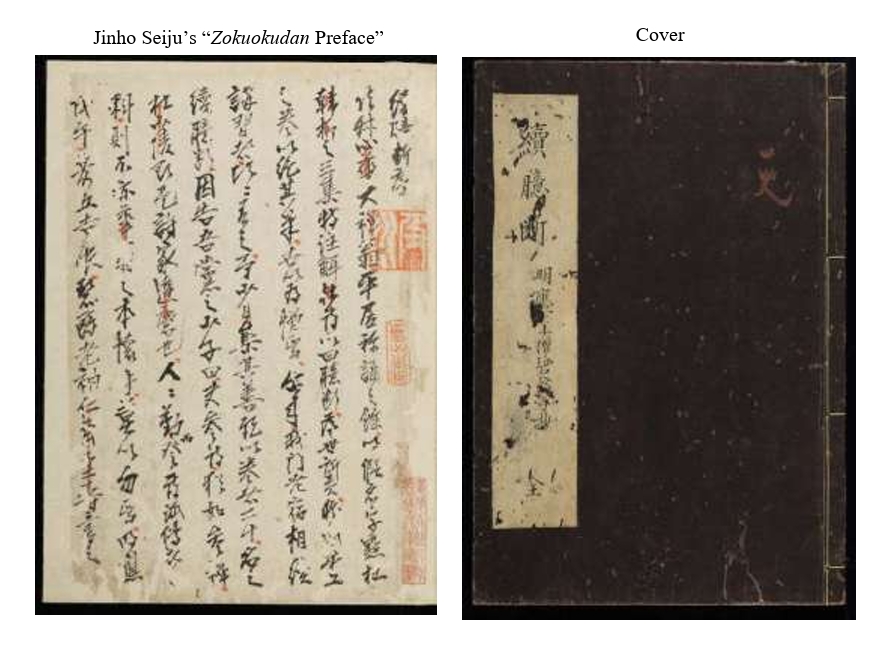

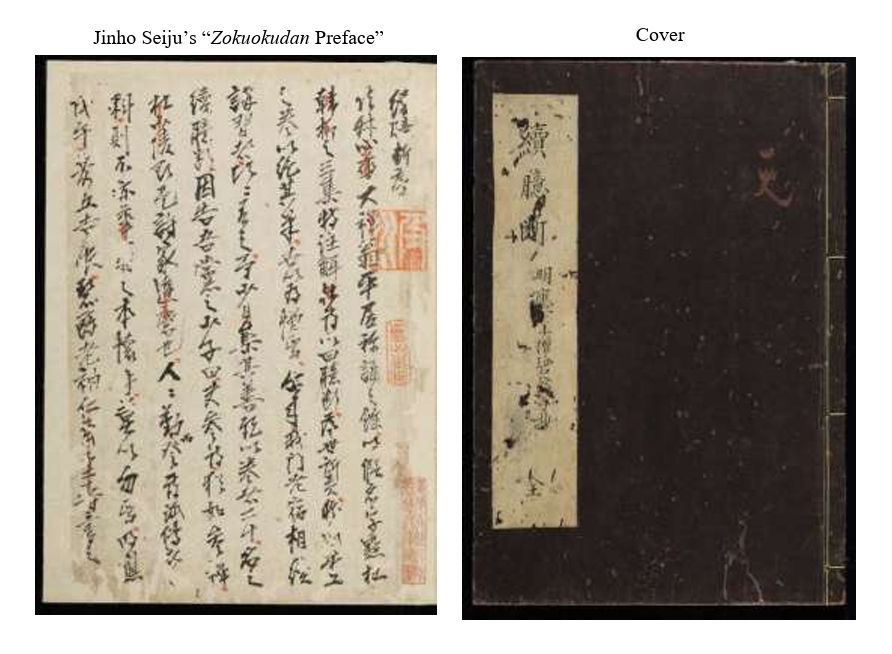

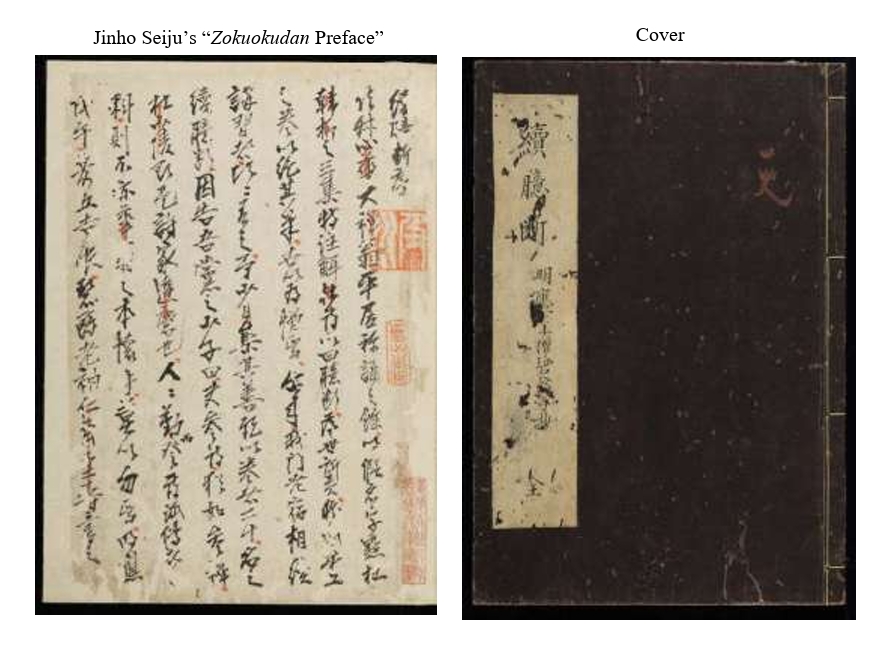

The existing

shōmono of Du Fu’s poetry from the later period of

gozan bungaku had traditionally been considered to be limited to the aforementioned

Toshi shō by Setsurei Eikin. However, according to the “

Zokuokudan Preface” 續臆斷序 in Volume 7 of

Kanrinkoroshuu 翰林葫蘆集 by Keijo Shūrin 景徐周麟, it had been known that there was also a

shōmono of Du Fu’s poetry titled

Zokuokudan by Jinro Seiju but it had long been thought that there were no etxtant copes. However, in recent years, it has come to light that the Institute of Oriental Classics (Shidō Bunko) at Keio University holds a bound volume containing four of the total twenty volumes—Volumes 1, 2, 17, and 18 (Volume 2 is intact, while the other three have missing sections)—bound together in the incorrect order of Volumes 17, 18, 1, and 2.

11 A draft manuscript with Jinro’s own preface from 1498 (Meiō 7), extensively corrected and amended through overwriting and pasted notes, composed entirely in classical Chinese prose as a commentary. Jinro was the disciple of a disciple of Shinge Gentei, making him the Dharma nephew of his Dharma uncle, Shinge. He inherited the work of his Dharma uncle, Shinge, and he continued the halted work from Shinge’s

okudan. The self-preface was thought to correspond to Volume 2, but in reality it extends to Volume 5. However, there were other later drafts with different arrangements.

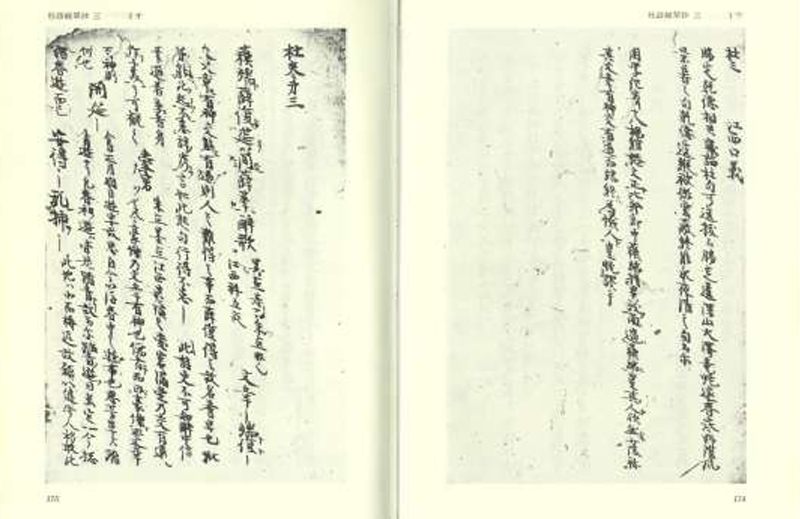

Jinro‚Äôs Zokuokudan also uses Ji qianjia zhu pidian du gongbu ji as its primary text, and it also references its annotations and the remarks of Liu Chenweng. Additionally, in Song Dynasty annotations, it cites references to Caotang shijian ËçâÂÝÇË©©ÁÆã with the mark ‚Äúcao,‚Äù Ëçâ and uses ‚Äúqian‚Äù ÂçÉ for references to annotations from Ji qianjia zhu fenlei Du Gongbu shi. Keijo Sh≈´rin‚Äôs ‚ÄúZokuokudan Preface‚Äù Á∫åËáÜÊñ∑Â∫è states, ‚ÄúAll reputable interpretations and commentaries from Caotang ËçâÂÝÇ and Qianjia ÂçÉÂÆ∂ were collated and appended beneath each line or passage, with notes distinguishing between acceptable and unacceptable views (e.g., ‚ÄòA is valid, B is not‚Äô), often supplemented by citations from poetic treatises as corroboration.‚Äù Furthermore, the annotation format generally begins by explaining the time period when the poem was composed, followed by the meaning of each couplet or stanza, then an explanation of the structure of the poem, and then ends with annotations on individual words and phrases. Since Zokuokudan is a continuation of the work of Jinro‚Äôs Dharma uncle, Shinge, it naturally contains numerous references to Shinge okudan in its annotations. Zokuokudan is a newly discovered material, and so far, the only published paper on it is Toru Ota‚Äôs ‚ÄúA Brief Glimpse at Jinro Seiju‚Äôs Zokuokudan (Held in the Keio Institute of Oriental Classics)‚Äù „Ä剪ÅÁî´ËÅñÂ£Ω„ÄéÁ∫åËáÜÊñ∑„Äè(ÊÖ∂ÊáâÁæ©Â°æ§ßÂ≠∏ÊñØÈÅìÊñáÂ∫´ÊâÄËóè) Áû•Ë¶ã„Äç, which appeared in the ‚ÄúAnnual Report on Du Fu Studies‚Äù ÊùúÁî´ÁÝîÁ©∂Âπ¥Âݱ Issue No. 4 (Bensei Shuppan, March 2021). Future research progress is anticipated.

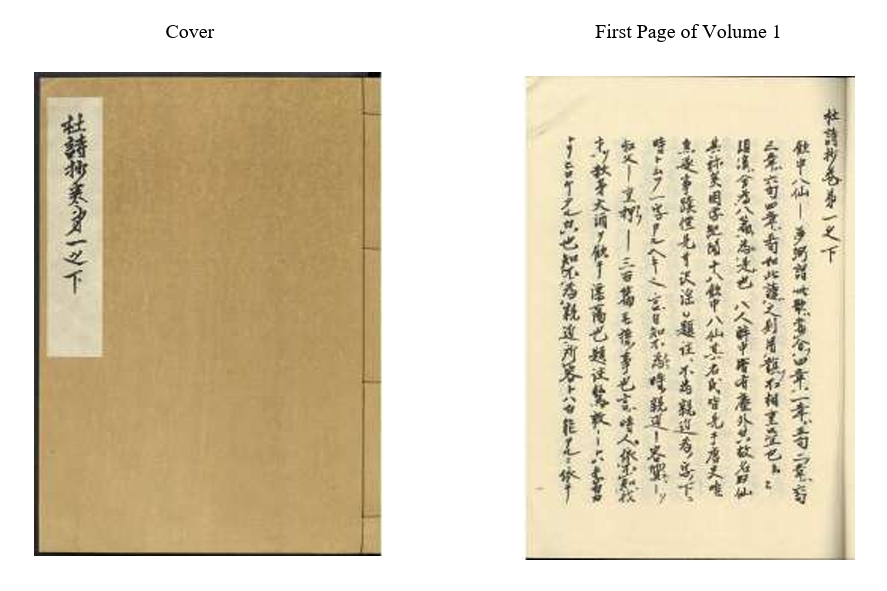

Title description: “Zokuokudan, handwritten by the monk Biweng in the seventh year of the Meiō period, complete.” 續臆斷 明應七年僧碧翁手抄 全 “Biweng 碧翁” is derived from Jinho’s pseudonym “Bi'ouzi” 碧鷗子.

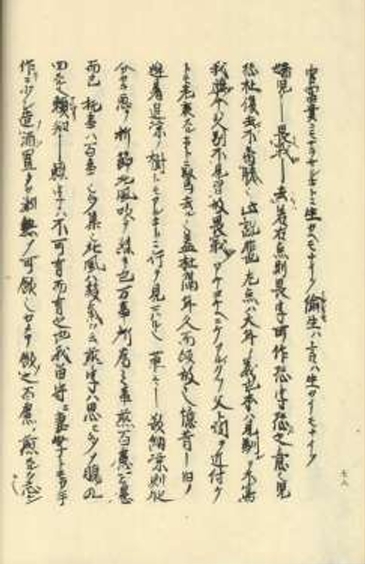

Zokuokudan, Volume 2, First Page

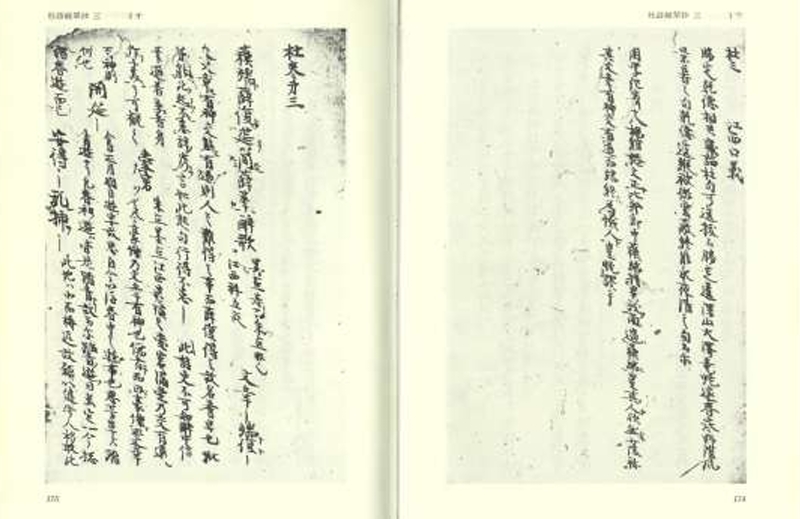

Setsurei Eikin’s 20-volume Toshi shō is the commentary book that concludes the line of shōmono related to Du Fu’s poetry. Two versions of this work still exist today. One is the 25-volume copy stored at the Kenninji Ryosokuin 建仁寺兩足院 in Kyoto. This version is missing the section “Qian” 乾 in Volume 3, and there are partial losses in Volumes 1, 2, 3, 18, and 20. It includes inscriptions written by Rin Sōji 林宗二 dated from the first year of the Genki era (1570) to the ninth year of the Tenshō era (1581). The writings are attributed to him, plus two other individuals (for more details, refer to Saburo Takami’s “Selections from Du Fu’s Poetry” 「杜詩の抄」). The other version is an incomplete copy up to Volume 12, consisting of eleven volumes that were re-copied from the Ryosokuin version. It is held at the Ashikaga School Iseki Library. This version preserved the first part of Volume 1, as well as Volume 2, the latter half of Volume 3 (“Kun” 坤), Volumes 5 through 9, Volume 10 (the first three poems are missing from the beginning), and Volume 12. The Ashikaga 足利本 manuscript was reproduced in facsimile along with a commentary volume that included texts by Toki Zenmaro 土岐善麿 (1885-1980) and Saga Kan’s 嵯峨寬 “Satsuki” 札記 (Kōfūsha 光風社, 1970–1973), but the Ryōzoku-in manuscript has yet to be made public.

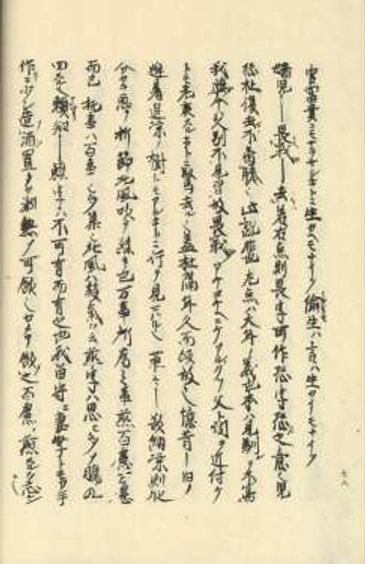

Setsurei Eikin’s Toshi shō (Reproduced by Kofu-kai from the Ashikaga School Iseki Library)

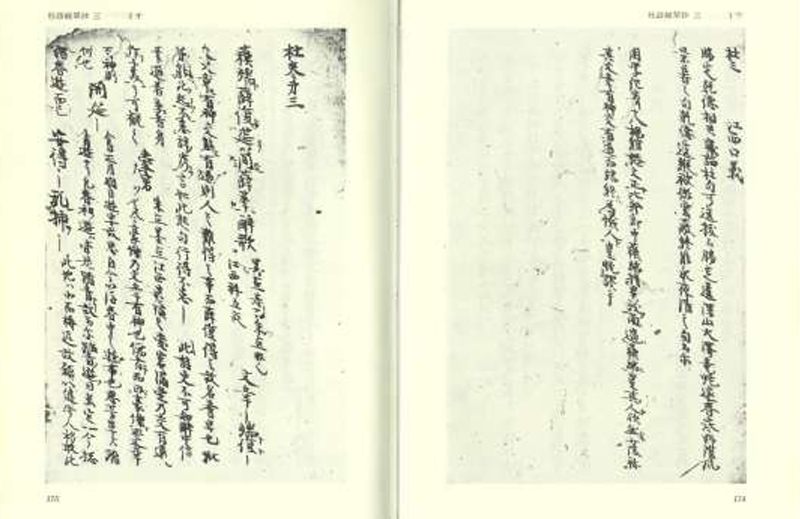

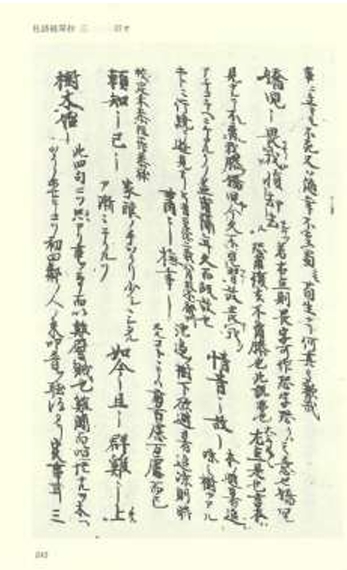

Setsurei’s Toshi shō was greatly influenced by Zokusuishō and inherited the annotation methods of Kōsei Ryūha. It is based on the Ji qianjia zhu pidian Du Gongbu ji as its primary text, while drawing upon Song dynasty commentaries such as the Caotang shijian and Ji qianjia zhu fenlei Du Gongbu shi, as well as earlier shōmono including Shinge okudan and Zokusuisō. As such, it can be regarded as a comprehensive culmination of Du Fu annotation within the Muromachi Gozan tradition. There is an especially large number of quotations from Zokusuishō, which had a significant influence on the work. However, it should be noted that citations are often omitted, requiring careful attention. Let us take as an example volume 3, section Kun 坤, from the second of “Three Poems on Qiang Village” (羌村三首), specifically the line “The tender child will not leave my lap, but, afraid of me, soon withdraws” (嬌兒不離膝,畏我復卻去). (Following the reading marks, kana have been supplemented where appropriate to render it in kana-based Japanese transcription.)

[Toshi shō (Ashikaga Version 足利本)] 嬌兒ーー、畏我ーー去

Interpretation of the latter line according to the left side’s kunten: 「我ヲ畏レテ復タ却キ去ル」(“Fearing me, the child moves away”)

Interpretation of the latter line according to the right side’s kunten: 「我ガ復タ却キ去〔ランコトヲ〕畏レテナリ」(“The child fears that I might leave again”)

The kunten on the right side suggests that the character wei (畏) can be interpreted as kong (恐, fear). Based on this interpretation, the child clings to Du Fu because he fears he will leave again. However, this interpretation is incorrect. The left-side kunten reflects the interpretation of Ta’nen (Shōtō). Before the separation, me and the child were close; he would never leave my lap. But, after being apart for so long, the child is no longer familiar with me and runs away in fear. After hearing that I am his father, he approaches, but my aged appearance frightens them, and he moves away. Indeed, Du Fu had been away for many years before returning home.

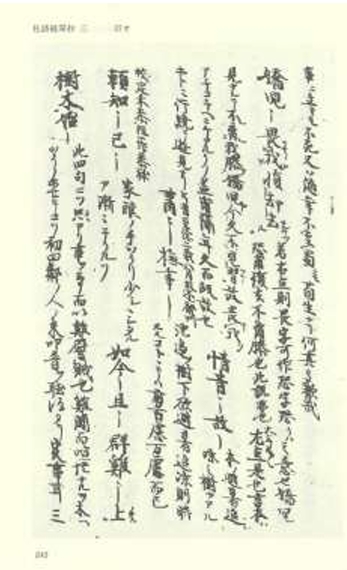

[Zokusuishō] 嬌兒ーー、畏我復却去

Interpretation according to the left side’s kunten: 「我ヲ畏テ復タ却キ去ル」(“Fearing me, the child moves away”)

Interpretation according to the right side’s kunten: 「我ガ復タ却キ去ランコトヲ畏レテナリ」(“The child fears that I might leave again”)

The kunten on the right side suggests that the character wei (畏) can be interpreted as kong (恐, fear). Based on this interpretation, the child clings to Du Fu’s lap because they fear he will leave again. However, this interpretation is incorrect. The left kunten (with a marginal note on the right side: “this is Ta’nen’s interpretation”) is correct. Originally, the child was very familiar with me, and wouldn’t leave my lap. But now that so much time has passed, the child isn’t used to seeing me, so he moves away in fear. Indeed, it must be because Du Fu has been away for so many years and has now returned home.

Aside from the underlined phrase, “After hearing that… he moves away,” Zokusuishou’s quotation is basically identical to Toshi shō’s. It can therefore be understood from this example that Setsurei utilized Zokusuishō and added his own interpretations when compiling his commentaries on Du Fu’s poetry.

This passage explains how the interpretation of the character wei (畏) is divided into two different theories, which are reflected in two types of kunten. Regarding this issue, Toki Zenmaro discusses in his essay “The tender child will not leave my lap: the Nuances of ‘Three Poems on Qiang Village’” included in the introduction to Toshi shō in Volume 4 of the Kōfūsha reprinted edition, that interpretations of the poem also differ between Japan and China. Both Kōsei Ryūha and Setsurei Eikin accepted the interpretation “Fearing me, the child moves away” (我を畏れて復た却き去る). However, there are many researchers today who support the other interpretation. It is evident from shōmono on Du Fu’s poetry that interpretations have been divided since the era of gozan.

In interpreting the poetry of Du Fu, annotated anthologies (shōmotsu) of his poems can serve as highly valuable references. However, shōmotsu introduced above still exist in manuscript form and have not yet been fully organized. Their transcription and scholarly analysis remain tasks for future research.

It can be said that shōmono on Du Fu’s poetry are extremely useful when it comes to interpretations. However, the shōmono introduced above are still in manuscript form and have not yet been fully organized; further interpretation and research are anticipated.

Setsurei’s Toshi shō, Volume 3 “Kun,” “Qiang Village,” Poem 2

Kōsei’s Zokusuishō Volume 3, “Qiang Village,” Poem 2

Notes

- Denecke, Wiebke. “Topic Poetry is All Ours’—Poetic Composition on Chinese Lines in Early Heian Japan.” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 67, no.1 (2007): 1-49.

- Haga K≈çshir≈ç Ëä≥Ë≥ÄÂπ∏ÂõõÈÉû. Ch≈´sei zenrin no gakumon oyobi bungaku ni kansuru kenky≈´ ‰∏≠‰∏ñÁ¶™Êûó„ÅÆÂ≠∏Âïè„Åä„Çà„Å≥ÊñáÂ≠∏„Å´Èóú„Åô„ÇãÁÝîÁ©∂. Tokyo: Nihon Gakujutsu Shink≈çkai, 1956.

- Hangai Yoshifumi ÂçäË∞∑Ëä≥Êñá. Chokusen san kanshish≈´ no kenky≈´ ÂãÖÊí∞‰∏âʺ¢Ë©©ÈõÜ„ÅÆÁÝîÁ©∂ (Research on the Three Imperial Anthologies of Chinese Poetry). Tokyo: Kenbun Publishing, 2022.

- Kyoto University Huang Colloquial Interpretations Research Group. Reading Shōmono: Overview and Commentary of Huang’s Colloquial Interpretations 抄物を讀む―『黄氏口義』提要と注釋―. Kyoto: Rinsen shoten, 2024.

- National Institute of Japanese Literature (NIJL). National Literature Database (國書データーベース). https://kokusho.nijl.ac.jp/biblio/100437682.

- Ota Toru §™Áî∞‰∫®. ‚ÄúThe Reception of Chinese Commentaries on Du Fu‚Äôs Poetry in Japanese Zen Temples: From the Ji qianjia zhu fenlei Du Gongbu shi to the Ji qianjia zhu pidian Du Gongbu ji‚Äù Êó•Êú¨Á¶™Êûó„Å´„Åä„Åë„Çã‰∏≠Âúã„ÅÆÊùúË©©Ê≥®ÈáãÊõ∏ÂèóÂÆπ‚Äï„ÄéÈõÜÂçÉÂÆ∂Ë®ªÂàÜÈ°ûÊùúÂ∑•Èɮ˩©„Äè„Åã„Çâ„ÄéÈõÜÂçÉÂÆ∂Ë®ªÊâπȪûÊùúÂ∑•ÈÉ®ÈõÜ„Äè„Å∏. Nihon Ch≈´gokugakkai h≈ç Êó•Êú¨‰∏≠ÂúãÂ≠∏ÊúÉÂݱ, vol.55 (2003): 240-256.

- ____. ‚ÄúA Brief Glimpse at Jinro Seiju‚Äôs Zokuokudan (Held in the Keio Institute of Oriental Classics)‚Äù „Ä剪ÅÁî´ËÅñÂ£Ω„ÄéÁ∫åËáÜÊñ∑„Äè (ÊÖ∂ÊáâÁæ©Â°æ§ßÂ≠∏ÊñØÈÅìÊñáÂ∫´ÊâÄËóè) Áû•Ë¶ã„Äç. Annual Report on Du Fu Studies ÊùúÁî´ÁÝîÁ©∂Âπ¥Âݱ, no. 4 (Tokyo: Bensei Shuppan, March 2021).

- Satou Michio 佐藤道生. Kudaishi Study 句題詩論考. Tokyo: Bensei Shuppan, November 2016.

- Takami Saburo È´ò˶ã‰∏âÈÉé. ‚ÄúToshi no sh≈ç: Toshi Zokusuish≈ç to Toshi sh≈ç‚Äù ÊùúË©©„ÅÆÊäÑ‚ÄïÊùúË©©Á∫åÁøÝÊäÑ„Å®ÊùúË©©ÊäÑ. Yamabe michi ±±ÈÇäÈÅì, no. 21.3 (1977).

- ____. È´ò˶ã‰∏âÈÉé. ‚ÄúToshi Zokusuis≈ç no shos≈ç ‚Äî Ch≈´gokugawa Toshi ch≈´shakusho o ch≈´shin ni‚Äù „Äå„ÄéÊùúË©©Á∫åÁøÝÊäÑ„Äè„ÅÆË´∏±§‚Äï‰∏≠ÂúãÂÅ¥ÊùúË©©Ê≥®ÈáãÊõ∏„Çí‰∏≠ÂøÉ„Å´‚Äï„Äç (The Layers of Toshi Zokusuish≈ç ‚ÄîCentered on Chinese Commentaries on Du Fu‚Äôs Poetry). Kokugo Kokubun ÂúãË™ûÂúãÊñá, 54 (December 1985): 1-13.